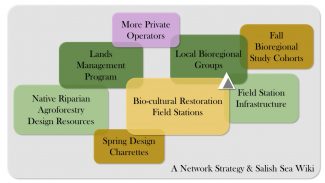

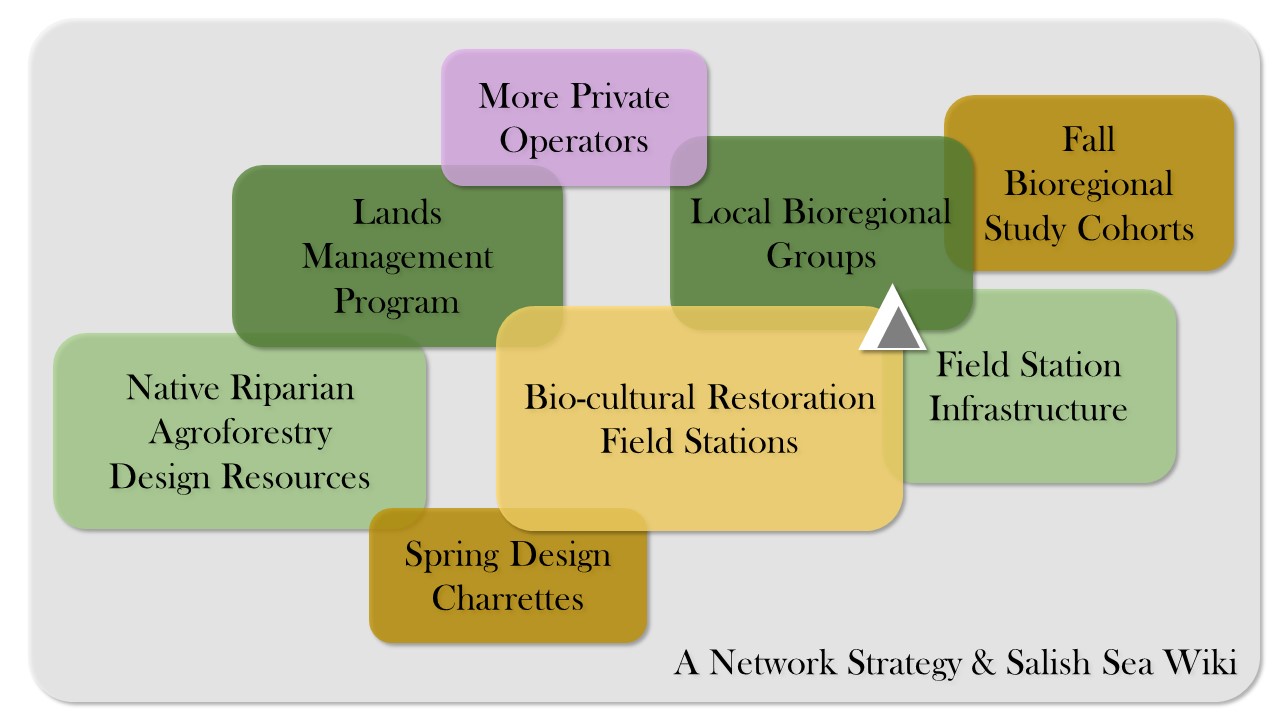

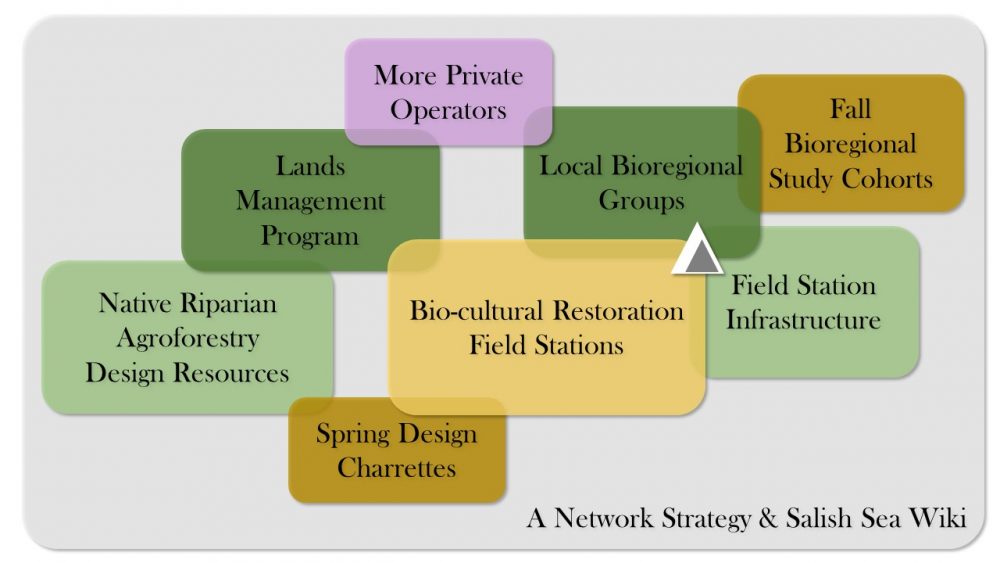

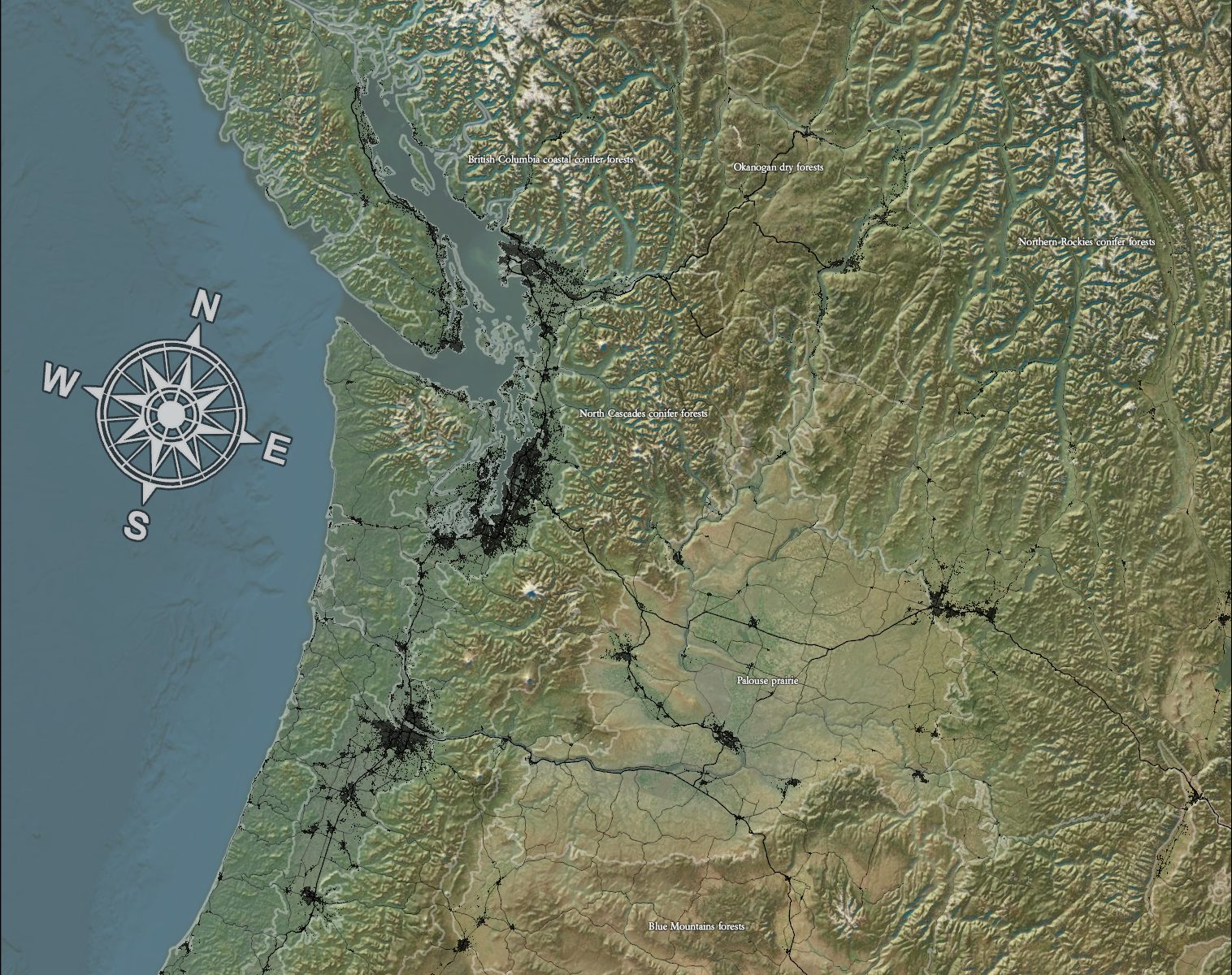

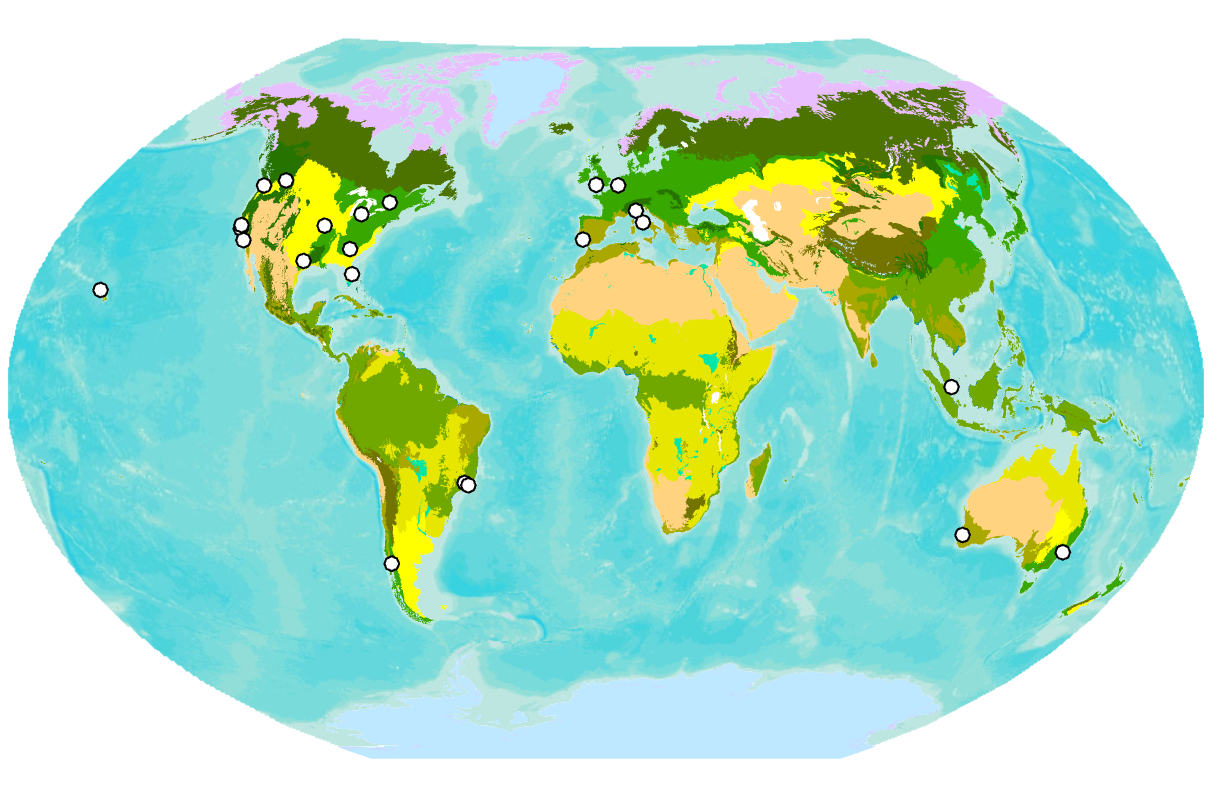

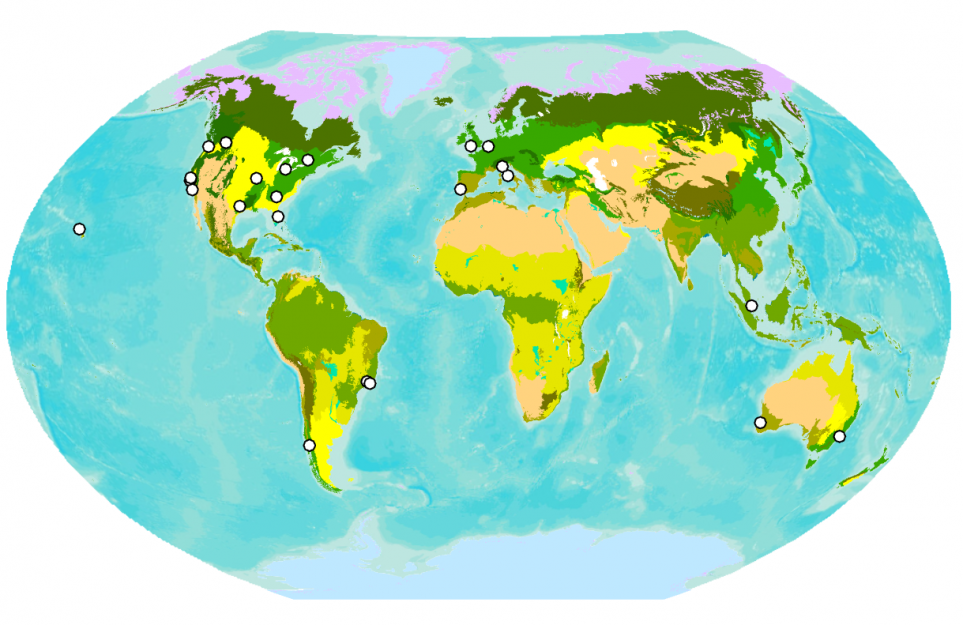

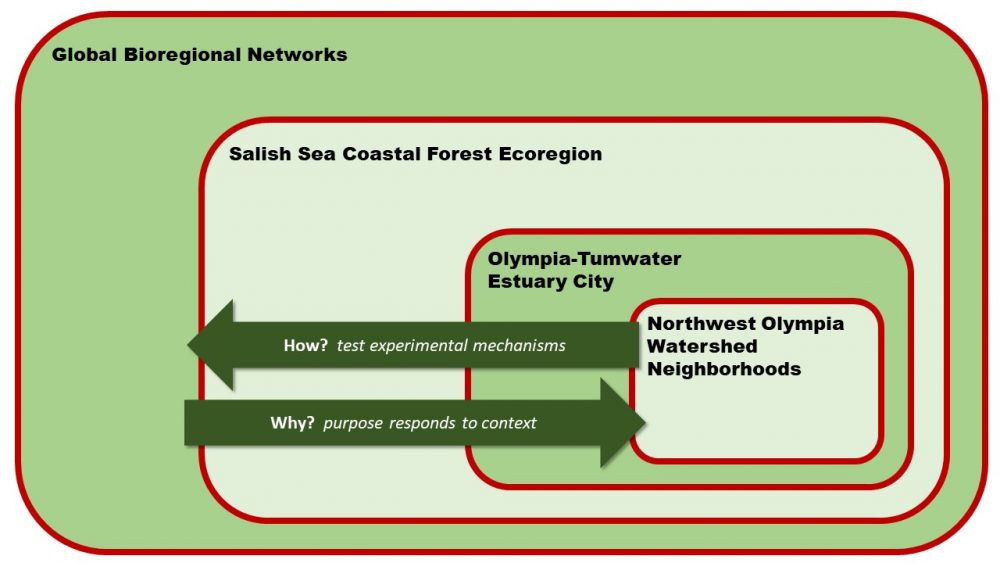

I am going to separate updates for different components of the Ecosystem Guild system, This is an update on Biocultural Restoration Field Stations. An overview of the big-picture vision is provided in update 11, referencing this diagram on the right.

Problem: Our public trust landscapes around aquatic habitats are neglected and have become the domain of experts and institutions. Study and work require preparations and cash flow among people at desks, and disempowers communities. Our social infrastructures around regulation, professionalization, liability, and private property prevent us from residing in, studying, and restoring an ecological commons. This undermines our capacities for group formation through natural work and further alienates us from the living Earth. Gathering at seasonal camps is the least expensive way to visit a place, and increases our connection to the land and each other. Shared residence and work rebuild relationships.

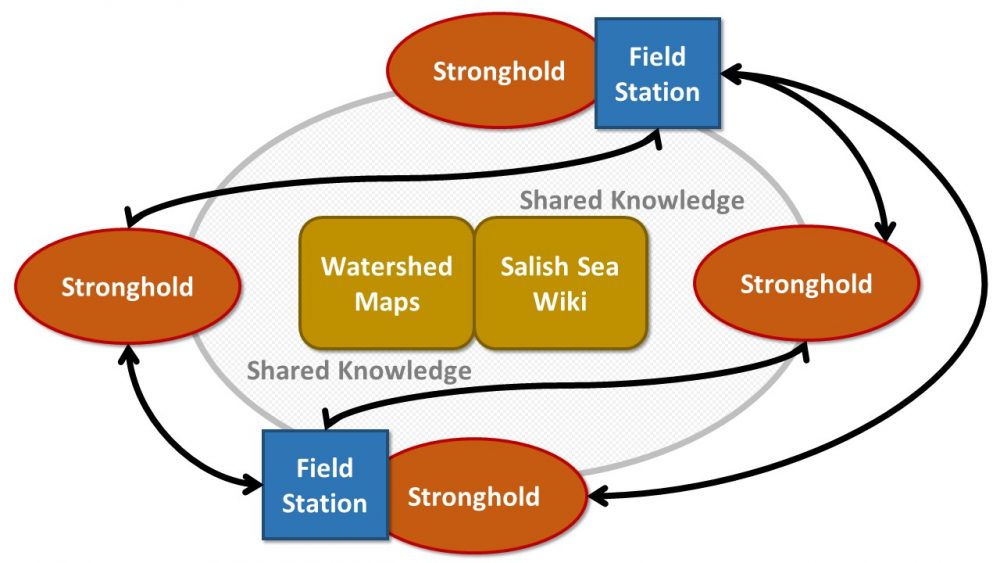

Target: Develop a culturally-motivated social process where groups can gather at conservation sites, for days to weeks, to work, build relationships, exchange knowledge and cultivate common pool resources (to restore the earth for both humans and other-than-human beings). A network of camps and institutions use a common protocol for establishing “field stations” and field stations become an organic co-learning environment that increases land access and tending. Field stations become a mechanism for mutual aid among strongholds. For 300,000 years in human culture, we tend places through inhabitation, working, eating, and telling stories around the fire.

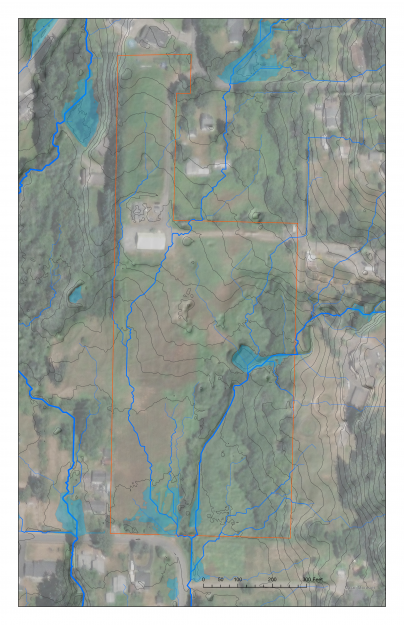

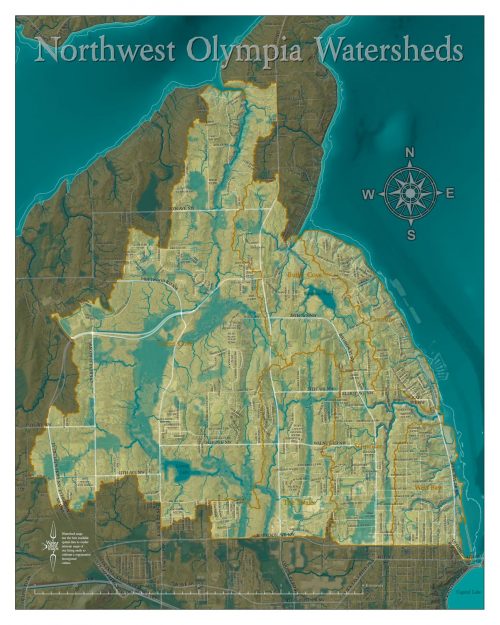

Tactics: identify initial willing land managers on public trust lands, host camping events around the restoration process, and prototype customs and infrastructure that enable self-organization and replication. Develop study and design resources that support this work. Build allies by providing a unique and valuable contribution in areas where the existing restoration industry is weak. We use the wiki to build shared knowledge. Field stations create and use watershed maps for learning, and communication, and as a knowledge store.

We’ve hosted two field stations so far. The Snohomish Conservation District workload has increased. They are unable to spare staff to chaperone the field station on a monthly basis, and so we needed to cancel March Camp. The CD has resources to support the field station, but just not the staff to manage all their resources. In April and May the Werkhovens asked us to not use the site to free up the roads for their operations. They are really busy with trucks and tractors in the planting season and don’t want any mishaps. While I think this is not necessary, and we could easily slip in and out without interruption, the relationship is young enough that it is not worth it to push the issue.

I had a good conversation with Earthcorp community engagement staff, both as a potential new relationship with an institutional sponsor and as a way to augment SCD staffing. They are focused on supporting environmental advocacy in communities of color in Tukwila, Burien, and Kent. Being able to provide opportunities for training and experience outside the city may serve their partners, and they will explore the possibility and report back. My intuition says our odds are above 50-50, but that it won’t happen fast, and Earthcorps will need funding to play the role. This is not a self-organizing solution because it is dependent on financial capital to scale, but has value in diversifying our community. Given all the dynamics I discuss below, I am starting to think that some kind of self-insured system may become necessary so that camps flow from a cultural demand of willing campers, not the ups and downs of institutional life.

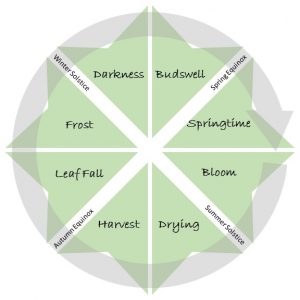

I am personally a bit overwhelmed with the many pieces of the larger guild effort and the unsteadiness of the initial field station infrastructure. The institutional sponsor piece is pretty foundational, and the unsteadiness there is very challenging. I am turning back to the eight-season year to try to make sense of it. How can the seasons and timing clarify what is important? How can I connect back to the seasons to pace myself? My wheelbarrow is taken apart in my shop next to a rocket heater project, next to several other projects. I’ve got nursery plants to get in the ground in my local greenbelt. I have seedlings to tend and a garden to dig. For me, there needs to be a rhythm to this.

I am shifting focus to design work with spring. My next hosting will be around a design experience at the new Conservation District Land in Lake Stevens in May. The CD bought 14 acres of headwater wetland and field just South of the UGA. This will involve a bunch of information development: plant lists, plant quantity calculation and cost estimates, reviews and interviews with regulators, exploration of state and federal subsidy programs, and profiling of native “crop plants”.

I have two other sites that seem very possible. One is a new conservation purchase in Thurston County, and the third is in Clallam County, an amazing saltwater site at a river mouth with an old wet prairie overlooking the strait. That site might come with a short-term institutional sponsor. In addition, I am still sitting on an old invitation to Lopez Island, and a new contact with what seems like a Bioregional Stronghold on South Whidbey Island. The institutional sponsor is really the limiting factor.

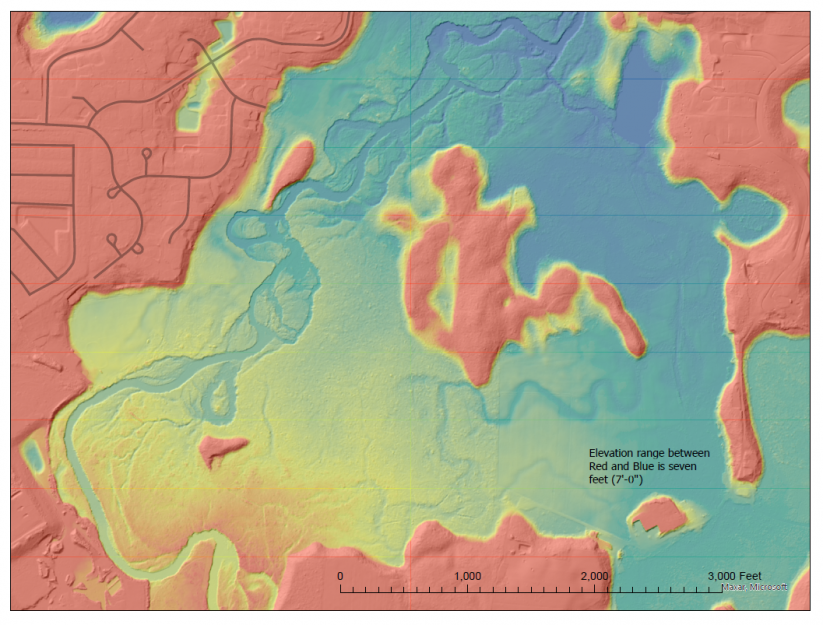

I am just starting up a conversation with folks involved in a 200-300 acre conservation purchase on the Deschutes River. It is a lovely site. I got to wander around the site, which is diverse large, and complex. But for the absence of willow forage, some channel incision, and old agricultural ditches the entire area would be a vast beaver swamp full of baby coho salmon.

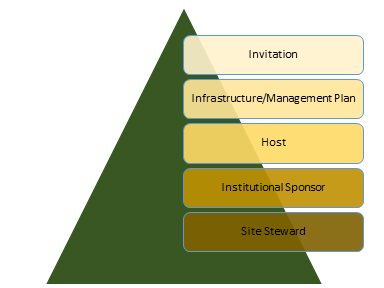

I think I am at a point where I need to expand the team that is thinking about how to increase the number of site stewards and diversity of institutional sponsors, while keeping some kind of coherence around a shared culture, to create the potential for ease and flow. Who is in a position to start thinking of themselves as a site steward?

The group formation aspect is still critical in my mind. If this process doesn’t encourage and lead to the formation of stable coherent groups within strongholds, I am dubious about the efficacy of the pattern. The flow of this experiment has been leading to relaxing the group formation requirement and creating ways for single individuals to join in. However, the group formation process needs to remain the clear directive. I have some work to do to model this within my own little stronghold.

February Camp

We did not have enough groups to have a field station in January, so regrouped on February 17-20. We had a small group brave winter camping.

In terms of schedule, we got lucky that the weather cooperated with the work schedule. Watching hourly weather forecasts will help stewards organize a time to minimize weather exposure. Working in the wet, there is definitely a period of time, after work, and before and during lunch where you just spend time cleaning up from fieldwork and switching to camp life. Cleaning and caring for tools and clothes after wet work is not minor. This all winds up with folks around the fire eating lunch, but this is typically a one-hour period and is not a fast transition.

Infrastructure Notes

Vehicle sleeping was definitely in vogue. If you are going to bring a weatherproof box to a winter camp, you might as well sleep in it. Weather is everything. We didn’t have wind, but that would have involved adding walls to the camp, which would have been critical to the group shelter (the great hall).

As expected, being able to dry clothing in a hot tent will be a useful piece of infrastructure for protracted work. Some form of continuous hot water would also be lovely. Some equivalent of a Russian samovar. I am hoping this will integrate with a rocket stove heater and the clothes drier. Various quick soups make perfect food.

We even had a bard (thank you Jack Jay for your poetry).

We really need to figure out an elegant solution for the floor of the great hall. Boots and dirt are not desirable. A shoes-off area around the fire creates the right vibe. The smokeless pits however focus heat up. Submerging the pit underground so the top is at the ground surface could create a desirable effect. straw could work with individual mats and chairs. Sparks from the fire are inevitable and destroyed two tarps, but the tarps were a reasonable option. The person-to-fire pit ratio is an important part of winter camping. Any more than eight people and a second pit would be necessary. We would benefit from a lot of jacket and hat hooks at the edge of the great hall.

Having dry storage as an annex to the great hall would work well. It was easy for the fire area to become cluttered with things that could have been tucked away when not in use. The clutter makes moving around difficult. As we learn to live well in the woods, we will bring more things than we need, which creates a detritus of modernity. When you multiply this by multiple groups, it can get out of hand.

This was the maiden voyage of the trailer serving as a kitchen and workshop. The hand wash sink also perched on the spare tire nicely. This is clearly the right direction and I have a page of design notes: lots of standing height counters (at just the right height), cubbies for segregating group food and dishes off the counter, hooks to hang food bags, a hanging rack to dry dishes at-hand but out of the way. The concept of a trailer with a large tarp roof adjacent to the great hall was just right.

I am starting to believe that alcohol burners are an elegant and appropriate cooking technology. The fuel is cheap and could be produced locally, there’s no soot from the fire, and they cook fast enough. Fuel is available, they are easy to move don’t take up much space, and are low-stress. Choosing simple one-pot meals with easy cleanup works well. Our traveling Buddhist pastor steadily produced some lovely one-pot soups with noodles–a good choice for a cold-weather lunch.

One of our numbers had just come from Hazel Ward’s Social Forestry Camp and we discussed their strategies for food, which involved collectivizing a pot of grain, but with smaller cooking groups each making their own stuff to go on the grain. Buckwheat (Kasha) is a nice choice for a fast-cooking grain compared to other choices.

A colleague is working on working through the mobile composting toilet challenge. The Omick Toilet is going to be the target. It seems like deposits will be easy and legal, but it is the land disposal after composting that will create challenges. I found a reliable seller of used plastic drums near Shelton, and I hope to do a prototype build in April.

Social Notes

I have been wrestling with the importance of the personal invitation. I am realizing that as a site steward, reaching out and inviting people, compared to broadcasting an opportunity, is an important part of the work. I want each of these wonderful people I have met to join me in this adventure. But they may only feel that desire if I reach out personally to invite them. This is part of what it means to be a host. It is also laborious compared to a mass marketing broadcast. We all lead complicated lives and invitation matters. I am not sure how I will evolve around this in the future.

On a more logistical side hosting a field station too close on the holidays seemed like folly. The only viable possibility would be for all group commitments to be solid back in December. Even then, short daylight hours combined with rain can make the work windows small. That is a good reason to jump on to plant in the fall, wait until Budswell to finish planting, and take a break in Darkness. I need to learn more about how much lead time a typical group or participant feels they need to join a field station. Part of the function of shared infrastructure is to make joining a field station easy. For many, car camping can be a lot of work to get ready, go, return, and unpack. Making that work less and less is part of the trick. When it’s smooth, it’s almost like emergency preparedness–like a go-bag under the bed. By having the core infrastructure well organized, you need only pack a sleeping kit, clothing, and tools, and fill a simple food bag on the way out of town.

It was a pleasure to meet two new colleagues from the Wilderness Awareness School attracted to and committed to the idea of land tending. This community is very close to my vision and hopes. A long while back, when I worked at Starflower Foundation, back in the late 1990s many of my colleagues were part of that diaspora. They brought a “sharing circle” practice to a campfire, which was lovely for me. It could feel intrusive or awkward for others. It opens different spaces for sharing and learning.

It was a boy-heavy event. Does that matter? Is there something to do here?

We noticed lots of jobs for camp tending. One idea would be to create roles on cards and hand them out at the opening circle so that everyone has a domain to tend to. This could be a lovely apprenticeship system as well.

We talked about the core skill sets that make camp stronger and came up with five:

- Camp tending – knowing the technologies and their care.

- Tool care – tending to metal and wood and sharpness.

- Natural history – including plants, animals, soils, and their dynamics.

- Environmental horticulture – the design and implementation of vegetation management.

- Site stewardship – the ability to establish the relationships necessary to bring a field station into the system.

Field Work Notes

We installed a small ~600 square foot dogwood garden into a blackberry patch and enhanced a few other dogwood patches along the swale with cuttings. We also removed blackberry from a Tulalip Tribes planting at “the old Scots Broom patch” as a courtesy to our host and established a trail from the railroad camp to that patch for future work. More details will go in the field station log.

Doing the site disturbance and preparations in the previous growing season, during fair weather has a lot of value. Having the ability to adjust the fieldwork in response to the rain helps the quality of the experience. Having the site disturbance complete, and just focusing on propagation creates a nimbleness with the weather where you can adjust the work period to match the weather. Not jamming site prep into planting helps avoid the impulse to take shortcuts driven by poor planning or the desire to get out of inclement weather that causes trouble later. We knew that we were going into a design-build situation, so kept expectations low.

To be able to plan ahead and commit to doing restoration work as part of a large community of hosts and stewards requires that groups can commit to getting the work done. A strong winter planting is the culmination of a year-long process of site disturbances and procuring the right propagation materials. We won’t be able to do high biodiversity rapidly developing plantings on well-developed sites without this commitment. So the uncertainty of who will show up at a field station creates a lot of tension on the restoration side.

One solution is to have contract crews waiting in the wings to fill any gaps left by volunteers. This is a common strategy and may be important for larger efforts. Alternately, volunteer work planning could include modest propagation goals, while filling any surplus capacity with tending and disturbance work that is not time-critical. Another strategy is to open the field station to volunteer labor through a traditional daytime work party. Two participants came as day participants. The idea of having the field station experience being a charade where commitment is assumed weak and the project is designed on the presumption that contracts and financial capital will be necessary to shore up these shortcomings… this just feels like the wrong evolutionary context. I suspect that having the work scale based on the capacity of the field station makes more sense.

Underlying all this is a pressure that I feel to show performance using the same metrics as the industry: acres restored. My heart tells me there is another larger longer body of work that is not recognized by that metric. Should I just be running volunteer work parties, where I do all the thinking and work, and pre-digest the effort–the plants laid out and the shovels waiting. Should I take all the agency and responsibility away from a community, and treat them like a work party, and in doing so, increase production efficiency?

In the same breath, the proof of maturity is to be able to get the work done. Part of the challenge is that revegetation happens on an annual cycle that requires some planning, and to be done well must occur in specific windows of time. If volunteers decide to not follow through or do something else this month, then the work doesn’t get done, the momentum created by a site steward is lost, work is wasted, and the seasons roll on. So one answer is to develop social structures that use money to impel the commitment necessary to assure production. Am I just reinventing the conservation corps, and will be driven toward this existing model, because that is what the culture can support?

Site Stewardship

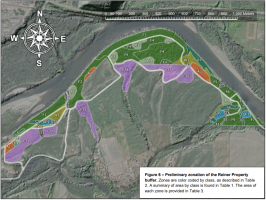

I have a draft stewardship plan to support coordination with our tribal government host, attempting to strike a balance between transparency and not over-specifying all the work, so we can be creative and responsive to the site. It has three parts: a map of vegetation patches, a strategy for each patch under management, and descriptions of treatments that describe what we do.

One dynamic I have noticed is how damaged land becomes a commodity in the restoration industry. Having access to a patch for restoration enables you to “sell” that acre in a grant application as “restoration”. Once thus sold, you are beholden to grant requirements, which may drive how and when you do restoration, regardless of what an optimum strategy might be at a site. Without these new acres to sell, you cannot justify more government funding and sustain your crews. Therefore various institutions are essentially in competition for patches of land to “restore”. After one treatment, the restoration is complete, stewardship ends, and the land is abandoned again. Many of the sites we identified in our site assessment as potential tending sites were unexpectedly adopted by the tribal revegetation crews, and will be the subject of the high-density conifer plantings supported by salmon recovery dollars–as is their right.

Interestingly, we were offered stewardship of a site that was planted with a high-density conifer planting around 15 years ago, that is now packed with conifers, with no understory, and where future forest health will be affected by the dense stocking rate. Some thinning makes sense. The initial proposal was that we would plant the site after a conservation corps chainsaw crew came through. Should we accept the mission, and depending on what the saw crew did, we might find ourselves clambering through slash planting shrubs? Site tending could be very difficult. Nothing but a “random plant and forget” strategy would be feasible if we inherited a hasty slash pile. If we had control of the thinning it could be more incremental and patchy, and we could donate the best greens to a volunteer wreath making effort (like the ho-ho-hobos) and use the poles or slash for camp infrastructure or deer exclusion, leaving the site easier to access for tending over time. Working next to the industry may prove to be a larger challenge than I imagined. The combination of the unpredictable capacity of the field station, the urgency of the grant-driven restoration economy that is clocking acres, and the expectation that professional work results in quick results combine to create a difficult operating environment to build community.

And yet this is the very tendency that I find myself struggling with in my daily work… the industrialization of stewardship comes with a cost.

Future and Needs

The short term is focused on onboarding our VetCorps intern at the Conservation District. We are lucky… I think this fellow will keep us on our toes. Spring and Summer will be spent in fieldwork and design, and hopefully some more sophisticated disturbances for next winter planting. This might be the chance to develop a vegetation ecology study of the Skykomish Valley and start building revegetation templates that consider what remains, and what has been lost. We are “restoring” the valley, and haven’t even assessed the condition and character of the landscape. So hasty. I am using the wiki to start to develop an onboarding self-study curriculum. I suspect this will continue to evolve over time, and into a series of different self-study options that build various skills. Lots to talk about on the wiki front, but that is another update.

We are also going to add the CD headquarters to our site list. This site is camping-ready and can serve as a regional mother garden. It also offers an opportunity to explore biocultural restoration in headwater wetlands. I have started interviews with regulators and immediately discovered that the concept of “disturbance” and “leaving nature undisturbed” is going to be a pivot point of that conversation.

I need to continue to identify the roles and needs of site group stewards so that individuals that are cultivating groups have the tools/language/permission to cultivate our culture on their own. In this way, I can make the work easier to see, and make good invitations. In the same way that I have been committed to a particular vision, I need to pledge my loyalty and support to those who would play these roles. They are who will make this vision sink or swim. Without commitment, communication, and consistency from groups, I cannot convince hosts that we are worth the trouble. This will be one of the threshold challenges.

So much more to write about, and lots of unfinished essays. But this update needs to get out the door.

Salish Sea Wiki – I have established a wiki page for

Salish Sea Wiki – I have established a wiki page for  Vegetation Survey Tools – I have published an initial plant list and survey tool on a google sheet. Walking onto a site and documenting species present is a basic practice which supports restoration or protection. These tool kits are being organized on the

Vegetation Survey Tools – I have published an initial plant list and survey tool on a google sheet. Walking onto a site and documenting species present is a basic practice which supports restoration or protection. These tool kits are being organized on the  Wangari’s Grove – At our first tree planting with South Sound Green Party we planting into a young forest at the Kaiser Entrance to Grass Lakes, now casually named after

Wangari’s Grove – At our first tree planting with South Sound Green Party we planting into a young forest at the Kaiser Entrance to Grass Lakes, now casually named after  Next Step – Marshall Middle School – I am meeting with the Citizen Science Institute at Marshall to figure out how an Ecosystem Guild could help them (see study). There is a patch of forest on their grounds as well several acres of potential reforestation. They have an existing nursery and want to get into propagation of native plants. They are connected to around 20% of the of the watershed population. They could use volunteers during school hours.

Next Step – Marshall Middle School – I am meeting with the Citizen Science Institute at Marshall to figure out how an Ecosystem Guild could help them (see study). There is a patch of forest on their grounds as well several acres of potential reforestation. They have an existing nursery and want to get into propagation of native plants. They are connected to around 20% of the of the watershed population. They could use volunteers during school hours. Next Step – Yogurt Farm – There is no restoration plan at the Yogurt Farm. Based on how City staff are talking, I expect this will be a second generation site, focused on successional design. Parks, with well timed advocacy from the Advisory Board, found money to install a trail from Road 65 to allow student pedestrian access. This connects to approximately 11 acres of potential reforestation.

Next Step – Yogurt Farm – There is no restoration plan at the Yogurt Farm. Based on how City staff are talking, I expect this will be a second generation site, focused on successional design. Parks, with well timed advocacy from the Advisory Board, found money to install a trail from Road 65 to allow student pedestrian access. This connects to approximately 11 acres of potential reforestation. Next Step – Kaiser Wetland NE Shore – We have two landowners who are interested in collaborative stewardship of a couple acres of young alder forest around an old Spruce grove, and next to some Capital Land Trust plantings on private and public lands. This could be The Guilds first foray into private land, once we have enough of a community.

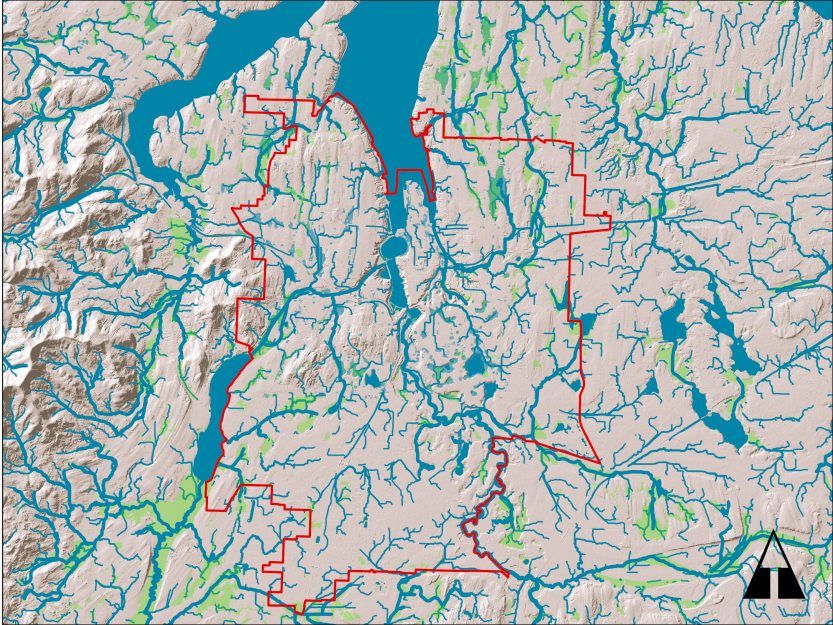

Next Step – Kaiser Wetland NE Shore – We have two landowners who are interested in collaborative stewardship of a couple acres of young alder forest around an old Spruce grove, and next to some Capital Land Trust plantings on private and public lands. This could be The Guilds first foray into private land, once we have enough of a community. Next Step – Watershed Analysis – The last undeveloped tributary into Green Cove Creek is largely owned by developers. There are exceptional restoration opportunities in large parcels along the upper Green Cove main-stem. Our best farm soils are at risk of being chopped into a large lot rural residential landscape. These opportunities, and development pressures has not been well defined. The City and County may not have the tools they need to make decisions. There has been no cumulative effects assessment of development on the stream. Both Wild Fish Conservancy and South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group are working on some habitat assessments in Green Cove Creek. I will be exploring various part of watershed analysis through interviews with Evergreen faculty to understand their interest and internship processes. I will need to work with or create institutions able to support interns.

Next Step – Watershed Analysis – The last undeveloped tributary into Green Cove Creek is largely owned by developers. There are exceptional restoration opportunities in large parcels along the upper Green Cove main-stem. Our best farm soils are at risk of being chopped into a large lot rural residential landscape. These opportunities, and development pressures has not been well defined. The City and County may not have the tools they need to make decisions. There has been no cumulative effects assessment of development on the stream. Both Wild Fish Conservancy and South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group are working on some habitat assessments in Green Cove Creek. I will be exploring various part of watershed analysis through interviews with Evergreen faculty to understand their interest and internship processes. I will need to work with or create institutions able to support interns.

Publish the eight season year as a framework – Six seasons are drafted–two more to go. Read more about

Publish the eight season year as a framework – Six seasons are drafted–two more to go. Read more about  Community weaving in the Green Cove Creek Watershed – Much of my work has been focused on getting to know the watershed communities. What an incredible community and place! Perhaps every place is a thing of beauty when fully appreciated. I’ve established a

Community weaving in the Green Cove Creek Watershed – Much of my work has been focused on getting to know the watershed communities. What an incredible community and place! Perhaps every place is a thing of beauty when fully appreciated. I’ve established a  Marshall Middle School Citizen Science Institute – In the middle of the watershed two middle school teachers are attempting to fully realize an integrated social and natural science-based education program. They have 60 students in an integrated half-day program and another 180 students/year involved in CTE programs around natural resource careers and horticulture. They have an existing garden/nursery, but want a stronger nursery plan. They are interested in shifting production towards native plants for watershed restoration. This team is adjacent to an alternative elementary school, and has access to a 19 acre, ecologically underdeveloped school yard located a 10 minute walk from a network of degraded headwater wetlands, but in many cases pedestrian access is limited due to property restrictions. Schools provide a natural social hub for child-rearing families across the watershed. We introduced Marshall to the Native Plant Salvage Foundation (who is interested in developing a network of school native plan salvage and nursery programs) This note may be a key target for a future grant, although we agreed that seeking a 2019

Marshall Middle School Citizen Science Institute – In the middle of the watershed two middle school teachers are attempting to fully realize an integrated social and natural science-based education program. They have 60 students in an integrated half-day program and another 180 students/year involved in CTE programs around natural resource careers and horticulture. They have an existing garden/nursery, but want a stronger nursery plan. They are interested in shifting production towards native plants for watershed restoration. This team is adjacent to an alternative elementary school, and has access to a 19 acre, ecologically underdeveloped school yard located a 10 minute walk from a network of degraded headwater wetlands, but in many cases pedestrian access is limited due to property restrictions. Schools provide a natural social hub for child-rearing families across the watershed. We introduced Marshall to the Native Plant Salvage Foundation (who is interested in developing a network of school native plan salvage and nursery programs) This note may be a key target for a future grant, although we agreed that seeking a 2019

WDFW supported a lecture on amphibian conservation we set up at the Unitarian Church. There is a USFWS team monitoring Olympia mud minnow in the Green Cove wetlands. This inter-agency sub-culture has the ability to put small bits of time into community projects, and can share high quality knowledge and advice, but typically doesn’t develop long-term relationships, and is preoccupied with funded work.

WDFW supported a lecture on amphibian conservation we set up at the Unitarian Church. There is a USFWS team monitoring Olympia mud minnow in the Green Cove wetlands. This inter-agency sub-culture has the ability to put small bits of time into community projects, and can share high quality knowledge and advice, but typically doesn’t develop long-term relationships, and is preoccupied with funded work. Farmers (sub-culture) – We have contacts among a scattering of crop farmers and grazers in the watershed, mostly clustered on the SW corner of the watershed, grazing goats, and running organic community-supported agriculture or intensive vegetable production operations. They are generally supportive of ecosystem conservation, have knowledge, skills and equipment, and also need to use a large portion of their land and labor for commercial food production to make a living.

Farmers (sub-culture) – We have contacts among a scattering of crop farmers and grazers in the watershed, mostly clustered on the SW corner of the watershed, grazing goats, and running organic community-supported agriculture or intensive vegetable production operations. They are generally supportive of ecosystem conservation, have knowledge, skills and equipment, and also need to use a large portion of their land and labor for commercial food production to make a living.