DRAFT

This is a framework for integrated social-ecological systems assessment to support the mission of the Ecosystem Guild. WARNING–very abstract stuff.

Stewardship is a two step dance. You observe and then you act. Then you do it over again[1]Different authors differ in their choreography of the dance, from Hollings’ early descriptions of adaptive management, evolved into the Open Standards for the Practice of … Continue reading. All of our knowledge, skills and technologies just facilitate this two step dance. We are trapped in the current moment, we learn by comparing present to past, and we speculate about the future. Stewardship of ecosystems is the ultimate strategy game[2]A portion of my fascination with this work, and my approach, comes from playing the classical East Asian strategy game of Go. Many complex games offer metaphorical guidance. We are all players.

Stewardship is a two step dance. You observe and then you act. Then you do it over again[1]Different authors differ in their choreography of the dance, from Hollings’ early descriptions of adaptive management, evolved into the Open Standards for the Practice of … Continue reading. All of our knowledge, skills and technologies just facilitate this two step dance. We are trapped in the current moment, we learn by comparing present to past, and we speculate about the future. Stewardship of ecosystems is the ultimate strategy game[2]A portion of my fascination with this work, and my approach, comes from playing the classical East Asian strategy game of Go. Many complex games offer metaphorical guidance. We are all players.

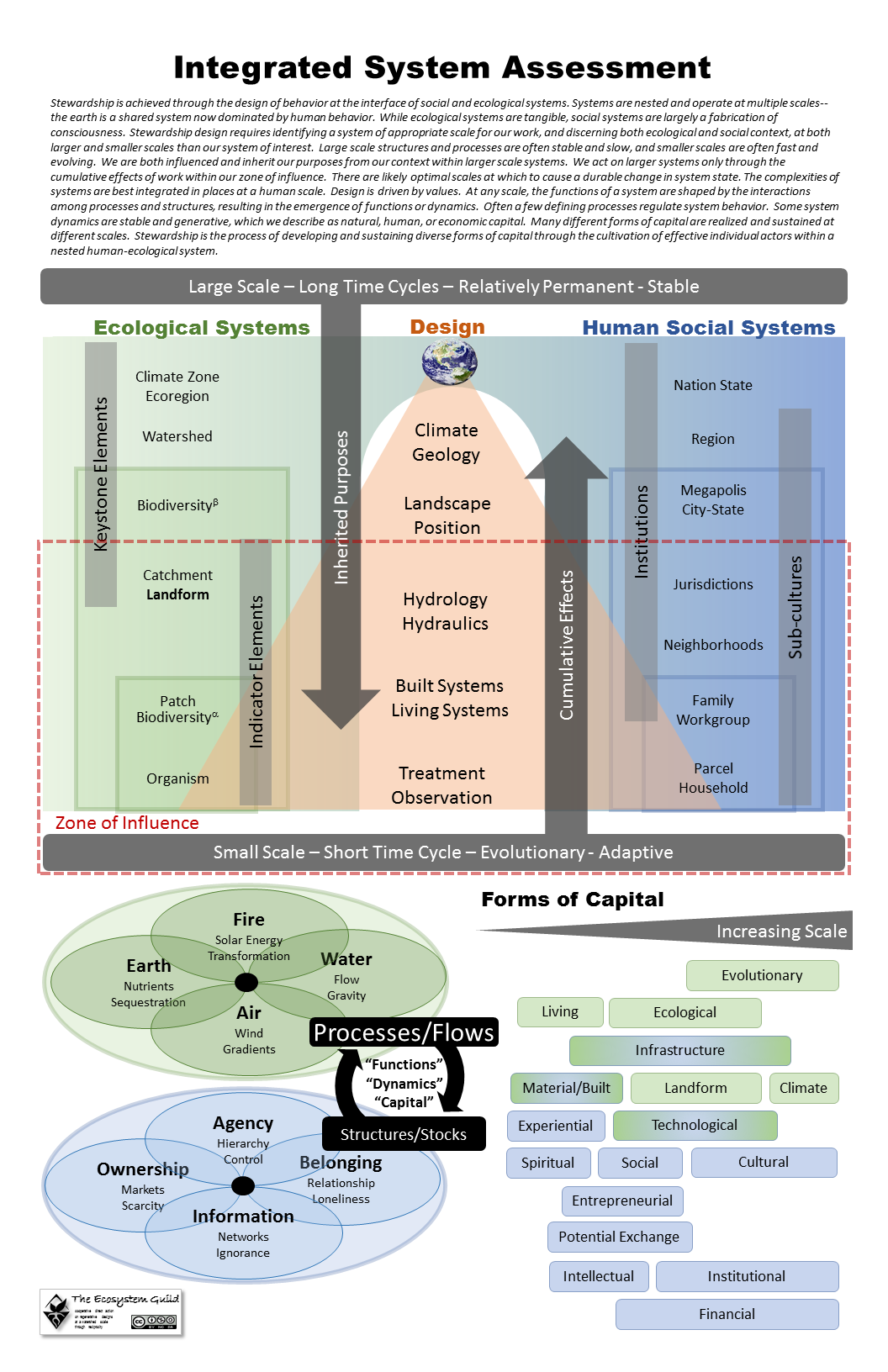

When I play a game, I like to have a strategy to organize my work. If we hope to play such a game as a community, a shared model is necessary to support our collaboration[3]Many strategic approaches depend on construction of shared models, such as Stroh’s Systems Thinking for Social Change, group exercises in Value Creation Chain evaluation proposed under Lean … Continue reading. In this infographic I offer my 30-year synthesis of how to assess the game board of ecosystem stewardship (also available in PDF format). It has been a vexing journey, and a learning experience, with ideas gathered from many different sources, so it seemed like a good idea to pause for a moment and try to scribble down a map. The next 7,000 words are just an expansion of this graphic. This is a draft and I have a lot to learn. Assessment of the design environment is so central to ecological work. I will likely be revising this the rest of my life. There are footnotes where I try to credit my inspirations. Thank you.

Before diving into the essay, here is the one paragraph version full of lingo:

“Stewardship is achieved through the design of behavior at the interface of social and ecological systems. Systems are nested and operate at multiple scales–the earth is a shared system now dominated by human behavior. While ecological systems are tangible, social systems are largely a fabrication of consciousness. Stewardship design requires identifying a system of appropriate scale for our work, and discerning both ecological and social context, at both larger and smaller scales than our system of interest. Large scale structures and processes are often stable and slow, and smaller scales are often fast and evolving. We are both influenced and inherit our purposes from our place within larger scale systems. We act on these larger systems only through the cumulative effects of work within our zone of influence. There are likely optimal scales at which to cause a durable change in system state. The complexities of systems are best integrated in places at a human scale through design. Design is driven by values. At any scale, the functions of a system are shaped by the interactions among processes and structures, resulting in the emergence of functions or dynamics. Often a few defining processes regulate system dynamics. Some system dynamics are stable and generative, and we describe these as natural, human, or economic capital. Many different forms of capital are realized and sustained at different scales. Stewardship is the process of developing and sustaining diverse forms of capital through the cultivation of effective individual actors within a nested human-ecological system.”

Ecological Systems, Human Social Systems, and Design

Ecological systems and human social systems interact, but are fundamentally different. Ecological systems are made of tangible features that can be measured. If we spend the time, we can sense the flows, fluxes, and transformation of energy, water, nutrients, and gases[4]This nomenclature for ecological processes is inspired by processes-based models developed Simenstad and others, and will be revisited later, however the division of systems into four elements … Continue reading. Human social systems by contrast, are mostly inside our heads.

Between ecological systems and humans systems there is overlap, where the ideas in our heads lead us to work on the land, and some of that work can change ecosystem state[5]“Ecosystem state” is common short hand for the structure of a system at a moment in time. In turn, our observations of ecosystems can inform the ideas in our heads about social systems. How we obtain resources and interpret scarcity is an example of this interaction. Our relationship with nature is a story in our head, that is played out on the ground. This”place and moment of social-ecological overlap” is important, because as ecological systems and human social systems collide it determines the fate of civilizations. Stewardship is focused on shaping this interaction so that it aligns with our values and sustains the well-being of our descendants.

My assessment of social systems is focused on humans. There are beaver social systems and wolf social systems that we barely understand. Humans, however, are the earth’s dominant ecosystem engineer. Our efforts eclipse the work of all other beings. We do not tolerate any creature that contests our domain. The global well-being of most species is now along for the ride as we careen along a precipitous road mountain, dependent on our ability to drive–our emerging capability of collective design[6]I suspect that collective design capability is different than individual design capabilities and that individual design capabilities may not be sufficient to solve ecological stewardship problems..

The global well-being of all species is now careening along a precipitous road mountain, dependent on our ability to drive–our capability for collective design (Image from Pakistan Today by Javed Azam)

For the purposes of stewardship our social system and the ecosystem are not separate. They are one integrated system. I often avoid the word “natural”. Both human-built environments and “wild” places are part of a single inseparable social-ecological system[7]The term “social-ecological system” has emerged in part form the adaptive management community described earlier, the subject of increasing scholarly work. Our built environments are just those patches of earth that we have most aggressively engineered. While we may wholly transform a watershed it is still an ecological systems. Our idea of being somehow outside nature is only a story of rapidly declining utility[8]This is not intended to suggest that when humans detach from evolutionary processes and systems that there are not consequences in our mental landscape. We could likely describe a wildness gradient … Continue reading

I am using the word “design” both broadly as a widely applicable process, and precisely, as a specific phenomena. We carry all kinds of stories and understandings in in the clutter of our heads. Not all of these affect our designs. Design is the mechanism by which we take the stories in our heads, and turn them into tangible work in ecological systems. Our designs may be simple or sophisticated, and stack one upon another. However, we still work one design after another, one work after another[9]It is important to differentiate between work and talk. It is the work that affects ecosystems, and the talk only counts when it changes the work. Sometimes our designs are so ingrained, and our work so ritualized that they are almost subconscious, like when we repeat our design for how we get to work in the morning, burning fuel and spreading copper dust and oil residue, racing along perpetually maintained travel paths, built of compacted rock and tar. We carry all kinds of values in our heads, but the ones that count are the ones that get into our designs and our work. The form of the dance depends on not only our values, but our ability to integrate our values into our design process. In this way I talk about design broadly as a process that everyone uses all the time for just about everything, but it is specifically how we translate internal or shared values into external work.[10]There is a feedback loop here, recently clarified by a colleague Joe Brewer, who introduced the concept of “social niche formation” whereby we create inherited infrastructures that guide … Continue reading

Design is the only mechanism by which we exert control over our behaviors. Our effectiveness as ecosystem engineers depends on our design skills. How our designs perform, depends on both intentions and how our designs are fitted to the design context. We can have good intentions, and bad designs and fail to express our values. Our ability to create an effective design depends on our ability to assess the design environment. If we get the assessment step of the stewardship dance wrong, the action step is more likely to be misguided and misshapen. This seems simple, except for the complexity of our design environment. We are working in both ecosystems and social systems, and both systems are operating at multiple scales simultaneously.

Scale As Both Purpose and Mechanism

“Little Wheel spin and spin, big wheel turn around and around…” – Buffy St. Marie (YouTube music video)

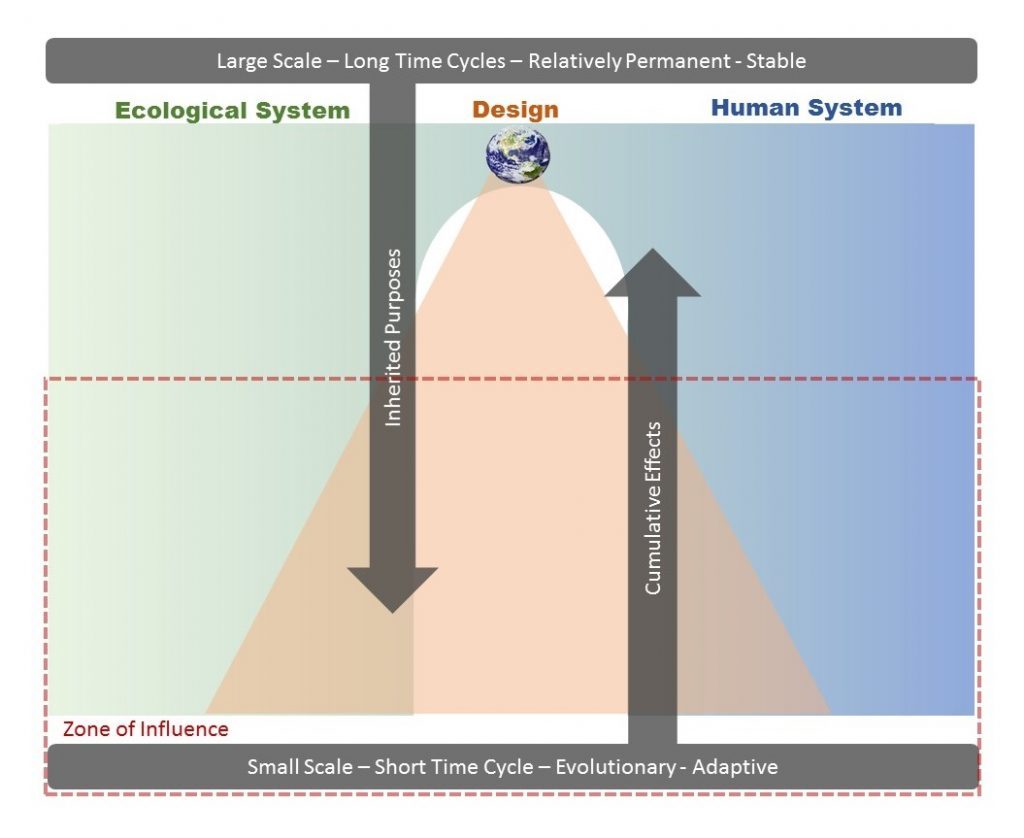

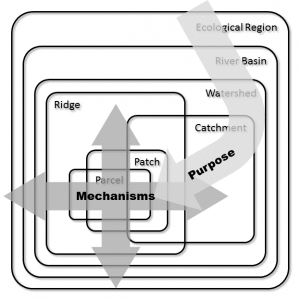

In my diagram, large scale systems are on top, and smaller scale systems are below. I could have just as well have drawn smaller scale systems floating in an ocean of larger scale systems. Small actions exist within a larger context. When you dig a swale, you are working within a soil series and in a hydrologic cycle. To understand larger scale systems we think about larger areas, and longer periods of time. Most of our lives are lived at smaller scales, over short time cycles, adapting to circumstance.

The large, long cycle systems in which we live influence the context for our work, both ecologically and culturally. Large global patterns of temperature and precipitation determines what lives or dies, from a tropical rainforest to an arctic desert. Among human systems, large, slow cultural stories about agency and ownership drive the structure of households and workgroups, from hunter-gatherer enclaves to the authoritarian networks at the heart of global empires[11]While this is a flip generalization, it is also intended to point at a particular aspect of context. Our social systems existing within a spectrum of co-mingled power structures. I believe J.C. … Continue reading.

There is a paradox here, because even as large long-cycle systems strongly affect our context, we also have a hard time observing these systems. We can’t “see” a civilization. “Seeing” large slow systems depend on the interpretation of diverse and diffuse evidence. The intellectual capital[12]there will be much talk of capital later which lets us comprehend ecosystems is a cultural artifact. Individuals within a sub-culture may reinterpret ecological evidence to fit their stories and beliefs[13]There is much recent consideration of confirmation bias as a human adaptation which can both stabilize and destabilize human systems. How we think affects our ability to comprehend the ecological system we are standing in. On the other hand, ecological systems don’t care what we are thinking about, only what we do.

If we want to be effective in the world we pay attention to what is going on around us. If you want to cross a river, you pay attention to the current and the river bed[14]This is not an accidental metaphor, derived from the Chinese proverb shared with me by John Liu, and I pick up the duality of recognizing both process and structure as a key part of design later. In this way, we react in response to larger scale context. In other words our context gives us purpose. However, these larger scale systems can only be altered by the cumulative effects of their smaller-scale evolutionary units (that’s us). This is a paradox. It suggests to me that there is a continuous and simultaneous flow of influence from large to small, and from small to large. The influence from large to small is powerful. We get this inheritance whether or not we like it. On the other hand our ability as small things to influence to large, whether forest health or a nation state, is not reliable, and so requires exceptional design, work, and adaptation over time.

“You don’t get to control what happens to you, only what you do about it” – The Random Factor[15]An old family friend changed her name to The Random Factor, and self published a book which discussed the phenomena of “resonance” which she described as the inexplicable reciprocal … Continue reading.

Scales in Ecological Systems

In ecological systems, communities of organisms are located in a particular physical position, within a physical landform like a ridge, valley, plain or plateau [16]While I say communities of organisms there is a real and useful discussion here about competing theories of ecological assembly that argue over the existence of “communities”. I think … Continue reading. These landforms can be organized into catchments and watersheds. Watersheds come in all sizes from massive to tiny. Watersheds either huddle within, or straddle, ecological regions, and climate zones. When I go for a walk I can observe individual organisms in patches. As I wander across a landform I can see patterns in the patches and how they sit in the landform[17]Precise definitions of landforms are provided by the science of geomophology and local analysis of landform is often more useful that global generalizations, for example Shipman’s Nearshore … Continue reading. I can use remote sensing, aerial photography or maps to start understanding a watershed. Through experience and research I can begin to understand ecological regions[18]for the purposes of stewardship planning, I believe the World Wildlife Foundation’s Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World is among the best complements to observation of raw temperature and … Continue reading.

In ecological systems, communities of organisms are located in a particular physical position, within a physical landform like a ridge, valley, plain or plateau [16]While I say communities of organisms there is a real and useful discussion here about competing theories of ecological assembly that argue over the existence of “communities”. I think … Continue reading. These landforms can be organized into catchments and watersheds. Watersheds come in all sizes from massive to tiny. Watersheds either huddle within, or straddle, ecological regions, and climate zones. When I go for a walk I can observe individual organisms in patches. As I wander across a landform I can see patterns in the patches and how they sit in the landform[17]Precise definitions of landforms are provided by the science of geomophology and local analysis of landform is often more useful that global generalizations, for example Shipman’s Nearshore … Continue reading. I can use remote sensing, aerial photography or maps to start understanding a watershed. Through experience and research I can begin to understand ecological regions[18]for the purposes of stewardship planning, I believe the World Wildlife Foundation’s Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World is among the best complements to observation of raw temperature and … Continue reading.

Ecological systems are not just a random collection of elements, but rather large systems, like ecological regions, watersheds and landforms generate a set of dynamics that limit or organize all the clumps of organisms. They define the problems we must try to solve, and so define our purpose. In our model, I call these forces “keystone elements.[19]This concept is rough–but essentially, some common aspects of a system are more important than others, because they fundamentally structure smaller scale phenomena. These elements may be … Continue reading.” These elements may include regular winter cold snaps, unpredictably long droughts, or the frequency of floods, in addition to biotic forces like beaver, or the moderation of climate and hydrology by communities of big old trees. These keystone elements of our systems write the big stories of place, and each patch inherits that story because of our position within a layered ecological systems.

On the other end of the scale spectrum, within each place, a particular set of features or biota tell a stories about the unique qualities of that place. These are “indicator elements”. If you see a meadow of mountain sweet-cicely (Osmorhiza chilensis) and bedstraw (Galium arvense) among dwarf shrubs in a river floodplain it might suggest vegetation moderated by elk (Cervus canadensis) and flood. The herbs are both weedy and travel by attaching to fur[20]This points toward another body of work focused on vegetation design around concepts of plant strategies, stress, disturbance, and the role of human work in changing the stress/disturbance mosaic, and the shrubs are dwarfed because of browse. These indicator elements (weeds) help us understand the larger scale nature of a place because they are a responsive to the keystone elements (elk and flood). If the story of elk is murmured and muttered over and over by indicators over a landscape, that is what leads us to identify elk as a keystone element of the ecological system, at the scale and cycle of the range and movement of the herd.

This interaction between large scale influences of climate and geology, and how survival strategies developed by organisms living in patches respond to these influences is the vast unfolding story of the evolution of life, which is our ultimate design context.

Scales in Human Systems

Human systems also structure and process over multiple scales. Unlike ecological systems that organize around physical and biological processes, social systems organize around shared stories in human consciousness. This may be what is most exceptional about humans–that we can create and sustain shared stories among vast populations that sustain collective behavior, sometimes in direct contradiction to ecological reality[21]A concept borrowed from Y.N. Harari’s Sapiens, which I enjoyed, even as his amateur evolutionary psychology is derided by students of human history, the vast majority of which had nothing to do … Continue reading.

We sustain and evolve our shared stories, in part, through institutions. Not unlike keystone species, legal, religious, or economic institutions have complex influences that are inherited by a local human system. We are born into institutions and may or may not be aware of their influence. Like a Jay hiding nuts anticipating the depth of snow, we are conditioned and adapted to survive in the social system in which we are formed[22]This concept of “social niche formation” is reinforced by both inherited social institutions and built infrastructure..

In a landscape shaped by institutions, extended families and workgroups may develop a sub-culture. A sub-culture is like an indicator species in an ecological system, telling a story of place–a social survival pattern in response to the disturbances and stresses of surrounding institutions[23]this reference to stress and disturbance is a second intentional reference to theories of ecological strategy and change including Competitor-Stress Tolerator-Ruderal (CSR) Theory and the Panarchy … Continue reading. Sub-cultures form around shared stories, beliefs, rituals and taboos just as different species are varied in their physiological adaptations[24]This framework describing the four elements of culture came from Javan Bernakevitch at All Points Land Design. Both institutions and sub-cultures reflect a history of human system evolution. Just as in ecological systems, every structure tells a story of past processes. Every cultural feature is a sign, like a bent branch or broken twig that marks a deer’s trail through the forest.

Not surprisingly, while ecological sciences are taught in most primary and secondary schools, we have no parallel curriculum about human systems. They are hard to measure. Experiments are difficult to control and repeat. When we study human systems, we are both observer and observed. A honest experimental construct can be laborious or even unethical to maintain. Our stories about ourselves are more defined by institutions and subcultures than any empirical consensus on the human condition. People get angry if you contradict their founding stories.

We are now at a point in history when big institutional relicts, like nation-states, monotheistic religions, and bank-debt currency systems dominate virtually every inch of the globe. Even within our global cultures, there are still weakly influenced zones where unique local sub-cultures dominate: in rugged undeveloped landscapes, and in underground economies of decaying supercities[25]this is an admixture of observations by J.C. Scott mentioned above, on the global supremacy of grain-based empires, and the retreat of hill-peoples, combined with analysis by Y.N. Harari around … Continue reading.

Organizing Design over multiple Scales

If you begin to see the world as a nested, multi-scale interaction of human and ecological systems, it is easy to be overwhelmed. Stewardship requires work. The art and science of design helps us develop work that is well fitted to the design environment, both human and ecological, so that our actions resonate with the influences of larger scale phenomena, and are more likely to create cumulative effects that reflect our values.

Keyline design was such attempt to find order. Percival Alfred Yeomans was an Australian mining engineer who envisioned what he called the “scales of permanence.” His hypothesis is that when conducting a design you assess and integrate the hardest-to-change elements of a system first (like climate and landform), and work down into the smaller scale easier to change elements of a system (like where to put a fence). In this way, your design features are well-nested within their context and serve many purposes. Design begins with climate, landform and the organization of water, and only then do we locate roads, fencing and buildings. Secondarily, Yeoman’s offered us a clear sense of agency–that we are here to maximize the potential of the system, with a focus on water and soil to build the health and resilience of our community[26]Yeoman’s most complete presentation of his theories may be The Challenge of Landscape written in 1958.. Yeoman’s scales of permanence was birthed amidst Australian grazing operations, and even as I simplify his elegant system, the underlying strategy remains essentially unchanged[27]The most recent refinements of the keyline scales of permanence can be found in The Regrarians Platform, under the stewardship of Darren Doherty..

This concept is very similar in posture to another piece of work, on the other side of the globe, from roughly the same period of time by Fiebleman who coined his “theory of integrated levels” in which he suggested that our understanding of each scale (which he called levels), depends on our understanding of associated larger and smaller levels, and that unique properties emerge with each successive level. In this way, both Yeomans and Fiebleman may have been indicator elements.[28]Interestingly both were individuals with professional land experience, who were trying to bring integrative thinking into ruling institutions during a period when knowledge in the academic world was … Continue reading.

Perhaps these principles of scale might apply to the design in human systems. If so we would first considers and integrate the factors that most strongly shape local context, and are most difficult to change. Only then can we effectively consider the opportunities for interventions that might shape larger social patterns. While this metaphor seems intriguing, how do we understand what aspects of human systems are most fixed and influential within a design environment? What elements of our social system are “keystone?”

To have a purpose in a large system requires clarity about our personal values[29]I suspect this is perhaps Mollison’s greatest contribution to ecosystem management through his permaculture framework by demanding ethical design first based on values rather than : care for … Continue reading. As we work within our zone of influence, where we can have a discernible effect, we can see how our interventions might cumulatively affect larger scale patterns and systems, if they create synergy with our networks. This aligns with the aphorism “think globally, act locally.” A more detailed construction might be: “use your values to assess purpose from global to local, and then design interventions within local systems that are most likely to create cumulative global effects.”

A System at the Right Scale

Each design intervention occurs within a social-ecological system. But practically speaking, how do we define the “system”? The beauty of systems theory is that we can draw a box around a system at any scale we want, but not without consequence. How we define our systems affects our ability to do work. For stewardship, what matters is the work. In short, the first step is to be somewhere. Because multi-scale design in social-ecological systems is very difficult, but is almost impossible if you are not thinking about somewhere in particular. It makes sense to make some kind of commitment to a place.

There are dangers in casting our systems too large. Our governments profess to manage national or state systems. Because these boxes are so large, we then divide our systems into topics, like flood, fish, farming, water supply, waste management, or transportation. Different agencies are created to work on different topics. In attempted efficiency, we assess and set policy at large scales, with little understanding of the interactions among topics or the particulars of neighborhoods. A story that looks good on paper may hit the ground in unpredictable ways, destroying as much capital as it creates, and generating unintended consequences.

Stewardship is the antidote to the weakness of this centralized plan development and institutional policy deployment. Stewardship revolves around something called a “place”. Within a place, we have the opportunity to integrate institutions and sub-cultures for the purpose of structuring the human-ecosystem interface. The various topics of government agencies can be reassembled back into an integrated whole[30]While I pass over this quickly, for those of us living in an industrialized empire, the challenge of reintegrating large institutional systems so they function well in a place may be a critical pivot … Continue reading. Our places are both social and ecological, and so the definition of a place requires assessment of both ecological and human social systems.

What is the right scale to design stewardship? If a design environment is too small, you will not be able to identify an intervention that has a cumulative effect in the ecosystem to achieve benefits only achieved at larger scales (for example recovery of a fish population). If your intentions are too small compared to the influences at work at larger scales you reduce your ability to be effective (for example modest restoration in the face of climate change, or inadequate tinkering in the face of rapid immigration). You can’t fix watershed hydrology on a single parcel. You can’t shift government policy in one household. This is not to discourage small scale moral action, but if we are designing effort in community, lets take aim at scale.

If your design environment is too large, you exceed your ability to take meaningful action that is responsive to the nuance of context. You waste effort because your actions are too generalized, and poorly adapted to the landscape you are trying to affect. You are easily overwhelmed by complexity, and unable to organize conflicting community needs and concerns into a mutually beneficial pattern. The number of people you need to involve to create a socially durable effect becomes unmanageable at large scales. Its easy to become lost or misguided.

Scale in ecological systems is largely a function of area, while scale in human systems in largely a function of population. This is important because we are looking for a right scale of assessment and action, optimal for affecting the human-ecosystem interface. Too small is ineffective, but too large overwhelms our capabilities. this optimal scale must consider both the ecological and human scale of you system. Thus the right scale for assessment and stewardship design may be smaller that ecologically appealing, as human population density increases. However, our ability to effectively steward community and ecological capital is more likely to pay off through cumulative effects, rather than grandiose schemes. [31]These hypotheses follow many influences from Kirkpatrick Sale‘s Human Scale, Shumachers’s Small is Beautiful, or Ignasi Ribo’s Habitat, all the way back to Greek debates around … Continue reading.

To make any sense of a design environment we must draw a box around a piece of the whole, and try to understand what is happening inside, and how it relates to the rest of the whole. I’d propose that for the purpose of ecological stewardship, that this box surrounds something called a “place”, which is neither too big nor too small, with size driven by population, and boundaries defined by a mix of hydrology and community experience. This size is particularly important because stewardship without work has no ecological meaning. By actually doing the work, we learn a great deal about exactly what we need larger scales of social systems to do to support stewardship in a meaningful way.

Processes, Structures, and Emergent Functions

To understand a system, we can cut it into parts. There are wet parts, dry parts, living parts, non-living parts, evolved parts and anthropogenic parts [32]I have become increasingly cautious in using the term nature or natural, as I find it imprecise. I try to reserve the term “natural” for those elements of a system that are the result … Continue reading. We can measure size and density and temperature. We can count individuals and patches, and convert the structure of our system into data. While structure is easier to measure, it is only a snapshot of the system. We can dissect and measure the broken musical instruments on a stage, but never hear the orchestra[33]When I was younger I was impressed by, Masanobu Fukuoka, an agronomist who invented a form of natural farming, and who made a strong critique of examining systems by dissection, from which I … Continue reading.

To understand a system, we can cut it into parts. There are wet parts, dry parts, living parts, non-living parts, evolved parts and anthropogenic parts [32]I have become increasingly cautious in using the term nature or natural, as I find it imprecise. I try to reserve the term “natural” for those elements of a system that are the result … Continue reading. We can measure size and density and temperature. We can count individuals and patches, and convert the structure of our system into data. While structure is easier to measure, it is only a snapshot of the system. We can dissect and measure the broken musical instruments on a stage, but never hear the orchestra[33]When I was younger I was impressed by, Masanobu Fukuoka, an agronomist who invented a form of natural farming, and who made a strong critique of examining systems by dissection, from which I … Continue reading.

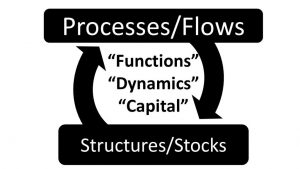

Systems are always cycling into something else, and the way that systems change are through processes. Processes include flows, transformations, and fluxes[34]This three fold taxonomy of processes comes from Simenstad and others and is part of a body of “process-based” restoration analysis, often shaped by the interaction of multiple physical and biological processes. Processes are described by observing the change of structures over time. Processes within processes shape structure, but structure also shapes process[35]In Meadows’ seminal primer Thinking in Systems, she describes processes and functions as flows and stocks. Some system mapping software describes edges and nodes. Other system models use … Continue reading.

This interaction among processes and structures creates the phenomena we see around us. These phenomena occur at all temporal and spatial scales[36]Or as they say in Star Trek and graduate school, “in space and time…”, and reoccur again and again: waves on a beach, the wetting and drying of soils, the accumulation of toxins in a food chain, daily rush hour, or the annual production of a vegetable grower. We call these durable patterns of structures and processes by different names: functions, dynamics, or in the cases, when a dynamic supports the stable and repeated generation of something of value, we call it “capital”.

These terms–functions, dynamics and capital–each have different shades of meaning, but I suspect that many of the fundamental attributes are the same. In the end, I suspect we should focus particular attention on forms of capital. These recurring elements of systems emerge from the interactions of processes and structures[37]Emergence describes a process by which complex systems generate phenomena that are not apparent within any one part.. So when we examine a system we look for structures and processes, and pay particular attention to processes as a generative force.

There are millions of processes occurring simultaneously at all scales, but not all processes are created equal. Some processes so strongly shape and sustain the structure of systems, that we make special note. While we appreciate all processes, as designers we are looking for those processes that most strongly shape or limit the structure of ecosystems. In doing so we can best refine our observations, and develop a stewardship strategy[38]I suspect there is a relationship between keystone processes and their scale of operation, such that larger scale processes equate with Yeoman’s higher scales of permanence, or … Continue reading.

Critical Ecological Flows

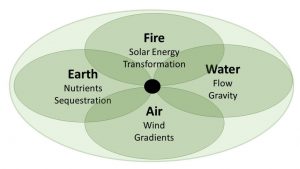

To understand a system we look for the processes that are doing the work to create and sustain important structures. Work over time creates the desired future social-ecological state, which is the goal of stewardship[39]The importance of recognizing processes in system change is identified by many authors and among many diverse systems, including Meadows, Holmgren, Simenstad, and Hollings among others. The beauty of process observation in ecological systems is that you can understand the dynamics of wildly different systems by looking at a few critical flows. These critical flows can be identified in any ecology text, and include:

- Energy, which flows from the sun as radiation, captured by plants and the mass of earth and water, and is then transformed again and again until lost to entropy as heat,

- Rare Earths, or nutrients which are either gaseous or mineral, and mobilized by temperature, water, and light, and provide the scarce building blocks of the carbon-based compounds necessary for life, specifically: nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur and another dozen and a half rare elements,

- Air, which along with water, provides a energy-driven circulation system by which heat energy and water vapor and even rare earths are distributed over the globe, and between oceans and continents.

- Water, which is in continuous cycle from pool to pool[40]A pool refers to a structure, where flows accumulate, driven by solar evaporation, air circulation and gravity.

It is no coincidence that these four flows were identified by Greek philosophers as the building blocks of the cosmos. Many scientists like to suggest that the four elements framework was discarded with the advent of elemental chemistry, only to come back around to the four elements in their conceptual modelling of ecosystems! Standing in a tropical swamp, or a boreal desert, you can typically understand the fundamental dynamics of your system of interest by observing the flow of these “elements” at multiple scales.

It is no coincidence that these four flows were identified by Greek philosophers as the building blocks of the cosmos. Many scientists like to suggest that the four elements framework was discarded with the advent of elemental chemistry, only to come back around to the four elements in their conceptual modelling of ecosystems! Standing in a tropical swamp, or a boreal desert, you can typically understand the fundamental dynamics of your system of interest by observing the flow of these “elements” at multiple scales.

Critical Flows in Human Social Systems

Compared to ecological systems, when we try assess human systems, we find ourselves relatively blind. We don’t teach a cohesive framework for human systems in primary or secondary school. Perhaps this is because the responsible adults spend their lives arguing around positions and policies, and lack a common framework for human system assessment. There are many confounding issues, creating an obstacle to stewardship design. Without an analysis of the processes and structures of human systems, we are only operating with half an understanding of the design environment.

As a restoration ecologist, I had no training in how to understand human systems. My family sub-culture introduced me to Marxist theory, but failed to teach me about financial systems, or give me experience in dominant legal institutions. In my youth, I was a student of astrology. The beauty of astrology is that it offers a thousand-year-old framework for human system analysis through a direct extension of the Greek’s four elements model–an easy road map for a lost ecologist. Astrological theory divides human systems into physical, intellectual, emotional and spiritual domains.

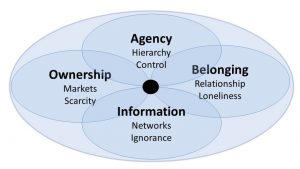

Later in life, with a little more experience, I stumbled into B. Guy Peters’ writing about policy alignment among social institutions. He identified hierarchies, markets, and networks as three distinct mechanisms for building social relationships that lead to coordinated action. Each mechanism varies in the durability and character of the relationships created. Peters’ framework enhanced my observations and fit neatly into my astrological taxonomies. The quid pro quo of markets was governed by earth, the networks of ideas ruled by air, and willful hierarchical control governed by fire. However, the emotional world of water was absent in Peters’ framework–perhaps appropriate for an academic focused on the power systems of nation states. I experience this emotional world as belonging.

Why wouldn’t human systems be governed by critical flows like ecological systems? Could we equip ourselves, like ecologists, to understand any system in which we were standing by assessing a set of critical flows? Could this help me navigate the design of stewardship systems?

Why wouldn’t human systems be governed by critical flows like ecological systems? Could we equip ourselves, like ecologists, to understand any system in which we were standing by assessing a set of critical flows? Could this help me navigate the design of stewardship systems?

Toward this end I have, for better or for worse, adopted an evolving admixture of astrology and contemporary policy analysis to frame my social systems. Over a period of several years it still satisfies my needs:

- Agency, is the flow wherein an individual cedes their agency to the will of another, often resulting in hierarchies. I suspect it is important to pay attention not to the accumulator of agency, but rather the process by which an individual cedes their agency as the source of the flow, just like the sun is the source of energy. Is not our will like a divine spark?

- Ownership, is the understanding among peoples over who has the right, often transferable, to use a set of resources, often resulting in markets where value is exchanged. It is important to recognize that even more than agency, defining and enforcing ownership systems is perhaps the essential purpose of states (which operate at large scales).

- Knowledge is difficult to control because it travels from person to person, combining and recombining unpredictably, and moves through decentralized networks. I have found information networks and nodes to be a critical tool for system design when you lack control over larger systems of agency or ownership.

- Belonging, the missing ingredient of Peters’ policy framework, and the glue which draws people together around a common affection for each other and place, built of trust and reciprocity[41]My consideration of belonging continues to evolve, through fellow ecologist Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, and Nenad Maljković’s recent essay on trust..

In this way any human might stand within a social systems, and by observing a set of key flows, discern some of the processes that drive system functions and forms of cultural capital.

Emergence and Forms of Capital

This brings us finally, long-way-round, to my stated purpose of assessment for stewardship design:

“Stewardship is the process of developing and sustaining diverse forms of capital through the cultivation of effective individual actors within a nested human-ecological system.”

Capital historically refers to financial capital, including built assets like factories, traded among capitalists and forming the “means of production and distribution” that defines our industrial age. The meaning of the term has evolved to include more sophisticated “human capital” as we started to invest more of the capabilities of institutionalized humans. Finally we’ve begun assessing “ecological capital” as we ponder the economic feedbacks and full economic costs of resource extraction. The colonial project is ending, as the serpent has found its tail. Ecological revenue is now an economic factor, even if born by future generations at a discounted rate[42]This is a placeholder for economic valuation of ecological capital which is problematic in the deepest sense of the word.. So “capital” has grown to encompass many “forms of capital” which together describe the stable generative functions of both ecological systems and social systems[43]As with the “ecosystem goods and services” language of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, there is a risk of misunderstanding the dynamics of systems by only valuing human services. … Continue reading.

Within the last couple years I have encountered two groups both describing forms of capital[44]Ethan Roland and Gregory Landua ‘s Eight Forms of Capital, followed by Hallsmith and Lietaer’s Growing Wealth, and I offer them here as a loosely organized pile of overlapping phenomena. Some forms of capital seem to only emerge at larger scales. Some only emerge under a complex combination of circumstances, and some obviously relate to each other. While I am using words I have gathered from others, I have added a few concepts of my own, focused on the emergent properties of large ecological systems. These proposed forms of capital are my reinterpretations, as I play with observing capital in the systems I work. There is no perfect framework only frameworks that serve different purposes imperfectly. I want to test the language describing key system flows (agency, ownership, information and belonging) in the context of understanding the nature of capital. Further, I also consider each form of capital as it might apply specifically the work of ecological stewardship. From this perspective I’d suggest that these “forms” are not discrete but rather overlapping and interdependent, and represent a confluence of processes and structures, which become stable and generative.

Within the last couple years I have encountered two groups both describing forms of capital[44]Ethan Roland and Gregory Landua ‘s Eight Forms of Capital, followed by Hallsmith and Lietaer’s Growing Wealth, and I offer them here as a loosely organized pile of overlapping phenomena. Some forms of capital seem to only emerge at larger scales. Some only emerge under a complex combination of circumstances, and some obviously relate to each other. While I am using words I have gathered from others, I have added a few concepts of my own, focused on the emergent properties of large ecological systems. These proposed forms of capital are my reinterpretations, as I play with observing capital in the systems I work. There is no perfect framework only frameworks that serve different purposes imperfectly. I want to test the language describing key system flows (agency, ownership, information and belonging) in the context of understanding the nature of capital. Further, I also consider each form of capital as it might apply specifically the work of ecological stewardship. From this perspective I’d suggest that these “forms” are not discrete but rather overlapping and interdependent, and represent a confluence of processes and structures, which become stable and generative.

I use the term capital very broadly, to encompass various forms of infrastructure, both built and living. I find myself using the term infrastructure similarly with poor separation between the two terms. Even as I might identify “infrastructure capital” following Hallsmith and Lietaer, I might turn and describe “cultural infrastructure” as social constructs that enable stewardship. Capital must be constructed at a particular scale, for its dynamics can function fully. A train track in not capital, as it only functions when it connects two stations that are placed within population centers. In some cases capital serves as a keystone element creating purpose within its system. In other cases capital serves as an indicator, a particular assemblage of resources responding to the demands of context. Understanding the forms of capital in a system, as a pattern of keystone elements, indicators, institutions and subcultures may be the critical step in integrated system assessment. Toward this end, it will likely be useful to understand capital as a emergent property of structures and flows–a dynamic of a system. A form of capital creates a pattern among critical flows of systems. From there we can diagnose the absence of capital, or design its regeneration. Lets look at that list:

- Cultural – an accumulated and shared body of stories, beliefs, rituals and taboos that enable groups of people to create value together. Culture spreads through networks but creates belonging, which motivates us to give our agency to shared ends. Undermining our analytical abilities, culture is nested within culture. It seems likely that “cultural capital” is just an imprecise umbrella for all non-physical forms of capital.

- Institutional – a kind of cultural capital where rituals and embedded into durable social structures, enabling more efficient mobilization of ceded agency. What are the institutions in your system, and at what scale and in what domains do they operate? By what flows do they sustain their structure?

- Intellectual – a particular understanding built of multiple experiences that can be stored and taught enabling technology. In what systems are our understanding of keystone elements and indicators stored? How is intellectual capital created, maintained and spread?

- Technological – a particular kind of intellectual capital which enables the conversion of material capital into infrastructure. Within our pools of intellectual capital, how do we develop and distribute technologies that enable stewardship?

- Experiential – the accumulation of experience within an individual, allows for that individual to apply skill to create value. What are the mechanisms by which individuals in the system can acquire experiences that build capital?

- Social – a network of individual-to-individual relationships which creates the belonging and trust which enables people to work for each others needs, or pool resources to achieve common goals. This capital appears to be an underpinning of a number of other forms of cultural capital. What are the sub-cultural networks that generate social capital in your system?

- Financial – the ability to aggregate ownership to achieve shared goals through the use of currencies, contracts, and shared ownership structures, largely mediated through monetary systems. Local financial systems are shaped by larger scale patterns of ownership and scarcity. What aspects of stewardship are valued by financial systems, and which are not?

- Potential Exchange – is a particular admixture to financial capital which describes our ability to orchestrate desired outcomes through currencies and exchanges other than the global system of bank-debt currency. What are the existing mechanisms of exchange other than money? What are immobilized assets that don’t flow because there is no mechanism for exchange? How do various fees and taxation drive economic activity towards bank-debt currencies?

- Spiritual – A sense of personal belonging to the unknown elements of the universe which gives individuals the will to exercise their agency. Spiritual capital seems to be built by experience and reinforced by institutional sub-culture. What are the underlying beliefs that shape our relationship to the landscape?

- Entrepreneurial – an emergent capital where a combination of capital enables individuals to pursue vision by reorganizing and creating new institutions. This is another specialized capital that has to do with the mechanisms that enable individuals to take experiential capital and use it to evolve institutions. This relates strongly to panarchy theory, and the tendencies for institutions to go through cycles of evolution and ossification[45]This whole concept of the timing of change in relation to the natural cycles of systems proposed under Panarchy will be brought up in part 2.. What are the mechanisms by which an individual can create new institutions that realize stewardship?

- Landform – the innate potential of the shape of a landscape to create value through the capture and flow of sun, water, and nutrients, or the presence of rare earths, within a given climate. What services does the landscape naturally produce that creates flows, both historically and currently?

- Living – The stock of organisms in our system that we can use to meet our needs. What are the goods and services that organisms in the landscape currently producing? What organisms were once present but are now missing? What are dynamics not supported by the existing assemblage?

- Material – Tools, materials, and machines extracted from landforms and living capital that enable efficient production and distribution, and allow us to modify ecosystems to meet our needs. What are tools that are available for stewardship: facilities, vehicles, hand tools, machinery with small and large engines?

- Infrastructure – the organization of material and technological capital into larger scale systems that allow for the increased efficiency in the application of collective work. What are the structures of the systems that enable transportation, waste re-circulation, information flow, social interaction, human health, water supply, and energy? Is this the right list of infrastructures?

- Ecological – the proximate organization of organisms into webs of relationships that produces resilient, low entropy systems that efficiently capture and use flows of water, nutrients and sun energy, while moderating climate. How is the living capital productivity or resilience affected by patterns of disturbance, stress, dispersal, refuge, predation, or mutualism?

- Evolutionary – the ability of living capital to evolve over time through ecological processes, thereby increasing ecological capital without human effort. Where are genetic resources at risk from non-evolutionary selection? Where genetic exchange and natural selection processes are compromised? What is the genetic state of the living capital which has co-evolved under human stewardship?

The art and science of stewardship is the process of tending and increasing these forms of capital within the systems in which we live. It stands to reason that system assessment involves these steps:

- Inventory of the various forms of capital present in our systems and the interactions among forms of capital.

- Identifying where shortages of capital prevent the fulfillment of values either because of influences from larger scales, or insufficient mechanisms at smaller scales.

- Assessment of how social and ecological flows limit the development of desired capital at the right scale.

- Identifying the appropriate scale for the efficient development of capital[46]This rough outline is a simplification of Savory’s Holistic Management framework, as presented by Bernakevitch, and will be picked up again in more detail with designing stewardship system … Continue reading.

- Where is a system dependent on external flows to sustain capital functions?

This assessment for stewardship has value when it leads to effective action. System assessment, informed by values, naturally beings to suggest weak links, and actions. System assessments in the absence of values creates large bureaucratic reports that have no meaning. Assessment of systems therefore hinges of values and what we hope to accomplish with our lives and our individual and collective agency. An assessment can begin with an individual, but becomes much more powerful when it becomes a shared body of intellectual capital, and an ongoing flow of knowledge and belonging within a human system. This said, I rarely share my assessment of capital at multiple scales with most of my partners in projects. These are diagnostic frameworks, shadows of reality, that help the designer perceive, and ultimately distill an intervention, which must then be tested in reality.

I still hold out hope that we can build towards common understanding. Stewardship enabled by cultural capital, rather than jury-rigged within a failing infrastructure. The challenge in operating at a meaningful scale is to build from individual agency to collective agency. This requires shared values and a shared understanding of the systems in which we are working. If we learn how to develop shared values that don’t distort our assessment of social and ecological systems, we may have a chance of getting where we want to go.

Intervention in the Zone of Influence

While much chatter is spent on large scale social and ecological phenomena (such as war, political contests and global crises) all these large scale dynamics are the expression of smaller scale dynamics which are shaped by large scale dynamics. When we glimpse of the world at large, what we see is little more than what we have built through how we live our collective lives, as well as what we have inherited from our ancestors. We may come to believe that the changes we desire are somewhere out there in that amorphous whole. However, it is clear that our agency is local and immediate. Our best information is local and immediate. From an ecological perspective, we only belong to the land we stand on and the people we are standing next to. The resources we actually have to work with are those in our hands. Our ability to create cumulative effect is through organization of our zone of influence.

Design is the process of converting our values into the systems in which we live. These systems are both social and ecological. We use capital to build capital. Capital is not created from nothing, but rather involves the reorganization of existing flows. If we design our work well we become more effective in the future[47]The refinement of adaptive management theory by Snowden’s Cynfin Framework provides a useful method for adjusting our decision approach to the complexity found in systems..

The process of envisioning a desired future state starts with a reckoning of climate and geology, including the cultural climate, and dominant institutions in which we have been born. Within that landscape we consider states, population centers and their institutions, as well as the flow of water, and recurring ecological keystone elements distributed among landforms. While considering the flows of critical resources, created by this pattern, we can begin to inventory forms of capital, in both living systems, built environments, and ecological systems. We compare this inventory of our capability to our values, and look for collective goals–what we want to build for the future. This is the platform that may enable collective integrated design. Any social-ecological vision is realized through a series of treatments and observations. Each treatment changes the stocks of capital required to create and sustain our desired future state. It begins with accurate assessment. Then you act, and assess again.

Part Two

I am currently working on a complementary infographic and essay focused on the process of designing a social-ecological vision, and working toward that vision through a series of interventions and observations.

I am grateful for any insight or discussion, through the Ecosystem Guild and Restoration Camping facebook page.

FootnoteS

References

| ↑1 | Different authors differ in their choreography of the dance, from Hollings’ early descriptions of adaptive management, evolved into the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation parallel to Holmgren’s principle “observe and interact“. Contextual variations are proposed by Snowden’s Cynfin framework. The underlying pattern of observe and act and do it over again is the same. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A portion of my fascination with this work, and my approach, comes from playing the classical East Asian strategy game of Go. Many complex games offer metaphorical guidance |

| ↑3 | Many strategic approaches depend on construction of shared models, such as Stroh’s Systems Thinking for Social Change, group exercises in Value Creation Chain evaluation proposed under Lean Management, or logic chain modelling in Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation. |

| ↑4 | This nomenclature for ecological processes is inspired by processes-based models developed Simenstad and others, and will be revisited later, however the division of systems into four elements is ancient and informs the later discussion of system flows |

| ↑5 | “Ecosystem state” is common short hand for the structure of a system at a moment in time |

| ↑6 | I suspect that collective design capability is different than individual design capabilities and that individual design capabilities may not be sufficient to solve ecological stewardship problems. |

| ↑7 | The term “social-ecological system” has emerged in part form the adaptive management community described earlier, the subject of increasing scholarly work |

| ↑8 | This is not intended to suggest that when humans detach from evolutionary processes and systems that there are not consequences in our mental landscape. We could likely describe a wildness gradient in human social systems as well as ecosystems. Emerging rewilding communities are actively exploring these concepts |

| ↑9 | It is important to differentiate between work and talk. It is the work that affects ecosystems, and the talk only counts when it changes the work |

| ↑10 | There is a feedback loop here, recently clarified by a colleague Joe Brewer, who introduced the concept of “social niche formation” whereby we create inherited infrastructures that guide future behavior without the need for conscious design. |

| ↑11 | While this is a flip generalization, it is also intended to point at a particular aspect of context. Our social systems existing within a spectrum of co-mingled power structures. I believe J.C. Scott’s scholarly exploration of the historical relationships between grain-based empires and their peripheral decentralized hill-peoples is an important exploration of this dynamic with modern applications |

| ↑12 | there will be much talk of capital later |

| ↑13 | There is much recent consideration of confirmation bias as a human adaptation which can both stabilize and destabilize human systems |

| ↑14 | This is not an accidental metaphor, derived from the Chinese proverb shared with me by John Liu, and I pick up the duality of recognizing both process and structure as a key part of design later |

| ↑15 | An old family friend changed her name to The Random Factor, and self published a book which discussed the phenomena of “resonance” which she described as the inexplicable reciprocal relationship between scales experienced in individual human lives. By doing so she planted seeds in my 12-year-old mind. When you search google for the random factor and resonance, you find engineering parameters. |

| ↑16 | While I say communities of organisms there is a real and useful discussion here about competing theories of ecological assembly that argue over the existence of “communities”. I think there may be some metaphorical importance there. |

| ↑17 | Precise definitions of landforms are provided by the science of geomophology and local analysis of landform is often more useful that global generalizations, for example Shipman’s Nearshore Classification, Montgomery’s local stream classification strategies, or syntheses that connect river process to channel pattern. |

| ↑18 | for the purposes of stewardship planning, I believe the World Wildlife Foundation’s Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World is among the best complements to observation of raw temperature and precipitation data , and the earth as a whole. |

| ↑19 | This concept is rough–but essentially, some common aspects of a system are more important than others, because they fundamentally structure smaller scale phenomena. These elements may be structures or processes, and physical or biological, or all of the above. |

| ↑20 | This points toward another body of work focused on vegetation design around concepts of plant strategies, stress, disturbance, and the role of human work in changing the stress/disturbance mosaic |

| ↑21 | A concept borrowed from Y.N. Harari’s Sapiens, which I enjoyed, even as his amateur evolutionary psychology is derided by students of human history, the vast majority of which had nothing to do with the dynamics of grain empires. |

| ↑22 | This concept of “social niche formation” is reinforced by both inherited social institutions and built infrastructure. |

| ↑23 | this reference to stress and disturbance is a second intentional reference to theories of ecological strategy and change including Competitor-Stress Tolerator-Ruderal (CSR) Theory and the Panarchy Hypothesis to be picked up again when we discuss stewardship design. |

| ↑24 | This framework describing the four elements of culture came from Javan Bernakevitch at All Points Land Design |

| ↑25 | this is an admixture of observations by J.C. Scott mentioned above, on the global supremacy of grain-based empires, and the retreat of hill-peoples, combined with analysis by Y.N. Harari around global systems of cultural homogenization. |

| ↑26 | Yeoman’s most complete presentation of his theories may be The Challenge of Landscape written in 1958. |

| ↑27 | The most recent refinements of the keyline scales of permanence can be found in The Regrarians Platform, under the stewardship of Darren Doherty. |

| ↑28 | Interestingly both were individuals with professional land experience, who were trying to bring integrative thinking into ruling institutions during a period when knowledge in the academic world was being balkanized into different specialized fields. |

| ↑29 | I suspect this is perhaps Mollison’s greatest contribution to ecosystem management through his permaculture framework by demanding ethical design first based on values rather than : care for land, care for people, and return of surplus. |

| ↑30 | While I pass over this quickly, for those of us living in an industrialized empire, the challenge of reintegrating large institutional systems so they function well in a place may be a critical pivot point for our careening civilization, and in developing adaptive capacity within our institutions. However our institutions do not typically recognize their weakness in places, or the opportunity for improvement offered by places. I suspect different subcultures will increasingly define themselves by their attitudes about our increasingly incompetent institutions from Kaizen Gemba to nihilistic forms of anarchism. I use the term “incompetent” here in a geomorphic sense, like a river that is not able to move its sediment. Our institutions may be structurally unable to accomplish the purposes being required by ecological systems. |

| ↑31 | These hypotheses follow many influences from Kirkpatrick Sale‘s Human Scale, Shumachers’s Small is Beautiful, or Ignasi Ribo’s Habitat, all the way back to Greek debates around community size and structure. |

| ↑32 | I have become increasingly cautious in using the term nature or natural, as I find it imprecise. I try to reserve the term “natural” for those elements of a system that are the result of evolutionary processes. But are not humans and our regnerative and degenerative impulses not an acting out of evolutionary process? |

| ↑33 | When I was younger I was impressed by, Masanobu Fukuoka, an agronomist who invented a form of natural farming, and who made a strong critique of examining systems by dissection, from which I gathered his broken instruments metaphor |

| ↑34 | This three fold taxonomy of processes comes from Simenstad and others and is part of a body of “process-based” restoration analysis |

| ↑35 | In Meadows’ seminal primer Thinking in Systems, she describes processes and functions as flows and stocks. Some system mapping software describes edges and nodes. Other system models use different labels like drivers, results, or outcomes, to describe the role of an elements within a logical chain of influences. |

| ↑36 | Or as they say in Star Trek and graduate school, “in space and time…” |

| ↑37 | Emergence describes a process by which complex systems generate phenomena that are not apparent within any one part. |

| ↑38 | I suspect there is a relationship between keystone processes and their scale of operation, such that larger scale processes equate with Yeoman’s higher scales of permanence, or Feibleman’s higher levels, and this logic may be useful in understanding the dynamics of human social systems. |

| ↑39 | The importance of recognizing processes in system change is identified by many authors and among many diverse systems, including Meadows, Holmgren, Simenstad, and Hollings among others |

| ↑40 | A pool refers to a structure, where flows accumulate |

| ↑41 | My consideration of belonging continues to evolve, through fellow ecologist Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, and Nenad Maljković’s recent essay on trust. |

| ↑42 | This is a placeholder for economic valuation of ecological capital which is problematic in the deepest sense of the word. |

| ↑43 | As with the “ecosystem goods and services” language of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, there is a risk of misunderstanding the dynamics of systems by only valuing human services. In addition Anand Giridharadas provides a robust critique of debating social justice without analyzing social systems, and his critique could extend well to an environmentalism that assumes extraction economies. |

| ↑44 | Ethan Roland and Gregory Landua ‘s Eight Forms of Capital, followed by Hallsmith and Lietaer’s Growing Wealth |

| ↑45 | This whole concept of the timing of change in relation to the natural cycles of systems proposed under Panarchy will be brought up in part 2. |

| ↑46 | This rough outline is a simplification of Savory’s Holistic Management framework, as presented by Bernakevitch, and will be picked up again in more detail with designing stewardship system interventions |

| ↑47 | The refinement of adaptive management theory by Snowden’s Cynfin Framework provides a useful method for adjusting our decision approach to the complexity found in systems. |