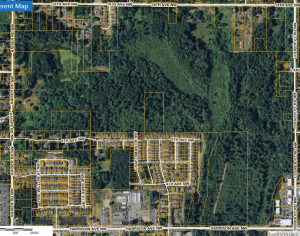

Time for a deeper update on my exploration of the Ecosystem Guild vision in Green Cove Creek Watershed. In the last installment (Update – 2018 Harvest) I resolved to temporarily shift focus away from restoration camping, and explore Green Cove Creek, to focus on the missing mechanisms necessary for communities to protect and restore watersheds in Lowland Puget Sound. I also concluded that restoration camping is all about people, and it seemed like Green Cove was a good place to start building a local community that could ultimately lead restoration camping in South Puget Sound.

This report is long so here is a one paragraph summary:

Summary – Over the last 6 months I produced eight essays, sketched a framework of restoration skills, contributed research to a fight over a watershed development proposal, developed conceptual design for a field station, developed and ran workshops on amphibians and hardwood cuttings, did a bunch of mapping and research, and supported a park planting. More importantly I became much more familiar with the Green Cove Watershed–below I briefly describe 24 institutions and sub-cultures in Green Cove. I initiated work between five watershed partners on a grant proposal that we agreed to postpone. All the makings of an Ecosystem Guild are present, but not integrated. We need a more robust systems to educate stewards, and to protect and restore the watershed. I propose an integrated model for building these capabilities, using a mix of on-line technical content, a project-based “open consultancy” teaching approach, and a flipped classroom model for skill building, based on evolving regional standards for restoration and protection practice. This allows us to begin on-the-ground work, as we build capabilities. There are many sites where we could begin, but I suggest two open consultancies on a private wetland-forest edge and a school mother-garden. Collective impact theory offers concepts for developing backbone functions to improve community performance. As we develop these pilot efforts, we can cultivate and test backbone functions that support future work. This strategy provides a clearer role for interns, and suggests two workshops, to initiate development of South Puget Sound revegetation standards, and to build community functions among Green Cove Watershed partners.

Report on Past Objectives

In my report last Harvest I set the following objectives, and have made some progress:

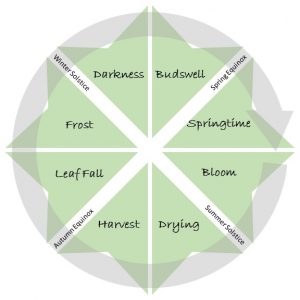

Publish the eight season year as a framework – Six seasons are drafted–two more to go. Read more about The Eight Season Year of the Salish Sea and how it defines both ecological and social work.

Publish the eight season year as a framework – Six seasons are drafted–two more to go. Read more about The Eight Season Year of the Salish Sea and how it defines both ecological and social work.- Develop a modular education strategy – I sketched a master list of skills necessary for restoration, and from these picked a core of skills that would allow a community to start restoring vegetation. I started a species list and recovered teaching aids from a previous school garden project. To minimize direct instruction I imagine a Flipped Classroom Model where individuals are able to self study, and we focus time together on learning through applying knowledge through field work. To support this I imagine organizing knowledge and skill learning around a set of standards for completing field work. We have concrete opportunities to run and refine standards in Green Cove at the middle school and college level over three sites (a school, a park, and private conservation parcels) where we can implement through a practice I learned from Darren Doherty called “open consultancy”. Read more below.

- Develop LLC structure – After investigation, I decided that piggy-backing on existing institutional structures is more efficient for the moment–becoming a volunteer in schools, NGOs, and the City. This “volunteer” status, done with full disclosure of my ulterior intent of restoring watersheds, also provides a deeper understanding of institutional sub-cultures. There will come a time, when it will be important to own collective property or manage liability outside the scope of existing institutions, and that will require a new institution. I have started framing a LLC operating agreement using a “sociocratic governance with planned mitosis” model (some of the possible functions are discussed below as part of Backbone).

- Develop and test a mobile field station – I have a bunch of sketches, have done some research into materials, but am still short of specifications for an initial build. My conceptual design is for a 4’x4’x8′ trailer box with a tool shed on one site, and a kitchen/classroom on the other, that unfolds to a 10′ x 24′ tent structure. Human waste would be managed through a bucket-based composting toilet. It still seems like a mobile field station may be premature, but will become suddenly relevant if we are ready to spend more time in the field away from infrastructure. Describing these systems will require another blog entry, and construction will have to be passed to collaborators or would pull me away from other activities.

Community weaving in the Green Cove Creek Watershed – Much of my work has been focused on getting to know the watershed communities. What an incredible community and place! Perhaps every place is a thing of beauty when fully appreciated. I’ve established a GIS and document archive. We’ve had two workshops on amphibians and cuttings, a planting work party with the city, discussions with the city about park access, and conversations around a prospective grant application, along with some social gatherings. I’ve had a large number of private conversations. My assessment of this community, and my plan for how to proceed is the bulk of my report below.

Community weaving in the Green Cove Creek Watershed – Much of my work has been focused on getting to know the watershed communities. What an incredible community and place! Perhaps every place is a thing of beauty when fully appreciated. I’ve established a GIS and document archive. We’ve had two workshops on amphibians and cuttings, a planting work party with the city, discussions with the city about park access, and conversations around a prospective grant application, along with some social gatherings. I’ve had a large number of private conversations. My assessment of this community, and my plan for how to proceed is the bulk of my report below.

To remain organized I like to focused on the desired end state–a social system capable of capturing rain, building biomass in forests and soils, and sustaining biological diversity (see Three Simple Goals), as a collaborative activity where everyone benefits through reciprocity (see System Among Neighbors). To achieve these goals, we need three tangible capabilities: the ability to restore, the ability to protect, and the ability to educate ourselves. In practice these three capabilities are intertwined and mutually supporting.

These capabilities largely depend on having the right forms of cultural capital present in the community (See Systems Assessment for Stewardship Design for a more abstract discussion of social flows and forms of capital). For these reasons, understanding the people in the watershed, and their institutions and sub-cultures is very important. People are the cradle of vision, investors in resources, and carriers knowledge. I start by reviewing 24 Green Cove institutions and sub-cultures I have observed.

I am trying to decide where to invest my efforts in developing “backbone functions” that are missing in the existing social system (for a simplistic example: Green Cove has abundant shovels, and students wanting to do work, but lacks a good plant species list, and nursery management knowledge). This is where an Ecosystem Guild could aim to catalyze community capability. The critical principle at work is to remain focused on the capability of the local social system to do the work. We are not colonizing a watershed community to support a new institution. We are strategically building relationships among existing institutions to create new watershed capabilities.

Institutions in Green Cove

I’ve had conversations with around 20 individuals involved in the watershed. I describe institutions and sub-cultures, in part to give individuals some privacy. I am increasingly convinced that our creations are largely built of relationships among individuals. Some people wield disproportionate creative or adaptive capabilities, or may be skilled at crossing institutional or sub-cultural boundaries. I believe deep watershed stewardship will depend on a diverse and inclusive network of these people.

Olympia School District – The school district has Career Training and Education (CTE) programs, that provides funds to schools and teachers, to give middle school and high school students work-like experiences. These programs attract students that are not engaged in sports or music or other extracurricular interests. There are allies in the watershed that are interested in developing a natural resource management CTE program at the high school level. CTE programs have access to resources that enable students to do real world work. Because of the overburden placed on teachers running these programs, they need help engaging professional communities, developing technical resources, and identifying meaningful watershed projects.

Marshall Middle School Citizen Science Institute – In the middle of the watershed two middle school teachers are attempting to fully realize an integrated social and natural science-based education program. They have 60 students in an integrated half-day program and another 180 students/year involved in CTE programs around natural resource careers and horticulture. They have an existing garden/nursery, but want a stronger nursery plan. They are interested in shifting production towards native plants for watershed restoration. This team is adjacent to an alternative elementary school, and has access to a 19 acre, ecologically underdeveloped school yard located a 10 minute walk from a network of degraded headwater wetlands, but in many cases pedestrian access is limited due to property restrictions. Schools provide a natural social hub for child-rearing families across the watershed. We introduced Marshall to the Native Plant Salvage Foundation (who is interested in developing a network of school native plan salvage and nursery programs) This note may be a key target for a future grant, although we agreed that seeking a 2019 No Child Left Inside grant was premature. We began negotiations with parks and local property owners to support pedestrian access to restoration sites.

Marshall Middle School Citizen Science Institute – In the middle of the watershed two middle school teachers are attempting to fully realize an integrated social and natural science-based education program. They have 60 students in an integrated half-day program and another 180 students/year involved in CTE programs around natural resource careers and horticulture. They have an existing garden/nursery, but want a stronger nursery plan. They are interested in shifting production towards native plants for watershed restoration. This team is adjacent to an alternative elementary school, and has access to a 19 acre, ecologically underdeveloped school yard located a 10 minute walk from a network of degraded headwater wetlands, but in many cases pedestrian access is limited due to property restrictions. Schools provide a natural social hub for child-rearing families across the watershed. We introduced Marshall to the Native Plant Salvage Foundation (who is interested in developing a network of school native plan salvage and nursery programs) This note may be a key target for a future grant, although we agreed that seeking a 2019 No Child Left Inside grant was premature. We began negotiations with parks and local property owners to support pedestrian access to restoration sites.

The Evergreen State College Programs – There are many faculty at The Evergreen State College that teach programs that consider some elements of watershed restoration. Evergreen programs are like tourists, in that they may visit the watershed but move on, preoccupied with paper studies and the resulting degrees. Some faculty are associated with durable campus projects (Natural History Museum, Ethnobotany Gardens, GIS Lab, Organic Farm) but are generally heavily burdened with teaching duties, and it will be difficult to cultivate strong commitments to watershed restoration. However, even the ephemeral attention of programs is the best way to connect with students.

Evergreen Students (sub-culture) – A 15 minute bike ride from the heart of the watershed, Evergreen students have a variety of opportunities to complete Student Oriented Studies (SOS) and Internships as part of their education, and are seeking practical experiences as an entry point to the job market. There is an internship database where The Guild could facilitate involvement of students. Graduate programs have mailing lists of students looking for research projects, and there is a community liaison for undergraduates. It is otherwise very difficult to communicate with students and faculty directly. Breaking into social networks will take some persistence. Interns require solid mentorship and deserve investment. Development of standard project-based practices can make intern entry into productive work easier for everyone. A reputation for providing good quality internships can increase the quality of candidates.

Stream Team – Olympia, Lacey, Tumwater and Thurston County are required to sustain a volunteer coordination, education and outreach system, as part of their NPDES permit under the Clean Water Act. Four stream team staff have varying professional skills and ambitions, but are directly charged with supporting watershed monitoring and restoration. They are also constrained by their institutional mandates, and shape their work based on personal interests. Stream Team also manages a regional mailing list of several thousand interested citizens.

Stream Team – Olympia, Lacey, Tumwater and Thurston County are required to sustain a volunteer coordination, education and outreach system, as part of their NPDES permit under the Clean Water Act. Four stream team staff have varying professional skills and ambitions, but are directly charged with supporting watershed monitoring and restoration. They are also constrained by their institutional mandates, and shape their work based on personal interests. Stream Team also manages a regional mailing list of several thousand interested citizens.

City of Olympia Parks – Grass Lakes Nature Reserve is a city owned wetland complex, with restoration potential at the Green Cove headwaters. Park staff are overburdened with general park management, such as maintaining trails, picking up garbage, responding to people living in the woods, and maintaining infrastructure and gardens. Parks has a volunteer program that is organized but small. Many neighbors don’t know that Grass Lakes Reserve even exists, and park staff are poorly positioned to develop networks within the watershed community. They do have equipment and budget for restoration, and a mandate to support restoration and environmental education, and establish public/private partnerships to maximize the public value of park properties. Parks is generally focused on their own properties and their own needs.

City of Olympia Parks – Grass Lakes Nature Reserve is a city owned wetland complex, with restoration potential at the Green Cove headwaters. Park staff are overburdened with general park management, such as maintaining trails, picking up garbage, responding to people living in the woods, and maintaining infrastructure and gardens. Parks has a volunteer program that is organized but small. Many neighbors don’t know that Grass Lakes Reserve even exists, and park staff are poorly positioned to develop networks within the watershed community. They do have equipment and budget for restoration, and a mandate to support restoration and environmental education, and establish public/private partnerships to maximize the public value of park properties. Parks is generally focused on their own properties and their own needs.

City of Olympia, Environmental Services – This small shop within Public Works is responsible for managing the hydrology of the City of Olympia. Each municipality has such a “surface water utility” authority, and raises revenue through a parcel assessment. These professionals have access to the inner workings of local governments, manage modest public budgets, own tools, and can provide technical assistance and project management. This team operates a small nursery for growing out bare-root stock, and has been working to accelerate restoration of city parks, but can also work in private greenbelts or public rights-of-way to achieve public benefits.

Agency Scientists (sub-culture) – I am lumping agencies and focusing on technical staff within agencies, because except for a few exceptions most natural resource agencies have no durable direct relationship with Green Cove Watershed. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife Service are the primary natural science agencies for the state and federal government respectively. They are loaded with expertise in a variety topics, such as amphibian ecology, fisheries. They have colleagues in USGS, Ecology, NOAA, WDNR and other agencies. Staff from Stream Team and  WDFW supported a lecture on amphibian conservation we set up at the Unitarian Church. There is a USFWS team monitoring Olympia mud minnow in the Green Cove wetlands. This inter-agency sub-culture has the ability to put small bits of time into community projects, and can share high quality knowledge and advice, but typically doesn’t develop long-term relationships, and is preoccupied with funded work.

WDFW supported a lecture on amphibian conservation we set up at the Unitarian Church. There is a USFWS team monitoring Olympia mud minnow in the Green Cove wetlands. This inter-agency sub-culture has the ability to put small bits of time into community projects, and can share high quality knowledge and advice, but typically doesn’t develop long-term relationships, and is preoccupied with funded work.

Native Plant Salvage Foundation – A small local volunteer NGO with two paid staff and an active board, has been salvaging and growing native plants. Native Plant Salvage sometimes serves as a contractor to Capital Land Trust and others doing native plant work. They offer plant ID training, including winter twigs, and are increasingly supporting school nurseries, and have long term relationships with an assortment of sites. They are willing to serve as a 501(c)3 fiscal agent if the project is right, but have very limited staff capacity to grow, and don’t have a mechanism for growing a larger staff without grants.

Wild Fish Conservancy – Wild Fish is a regional advocacy, science and restoration NGO, but some of their science staff live in the watershed, and have been tracking the chum salmon run on Green Cove Creek. This brings fishery knowledge to the watershed. In addition WFC has supported mud minnow research, and has specialized in using rigorous methods to expand local government protections under existing rules by documenting fisheries.

Capital Land Trust & Partners – There are eight parcels near the north end of the Kaiser Swamp, and abutting Evergreen land, where easements or title owned by CLT. They have a restoration, stewardship, and outreach staff, working across all CLT holdings, and they are interested in collaborating on watershed stewardship. In general, they limit public use, but are exploring how to increase public access to some sites. CLT has a regional donor network, but has not been pursuing acquisition in the watershed lately for a variety of complex reasons. CLT provides a bridge to a population of private conservation land owners, and is exploring increased public access to its holdings.

NIMBYs (sub-culture)– There is a network of individuals with some legal and science experience that come out of the woodwork to fight development proposals. This includes people active in local neighborhood association. The latest recurring conflagration has been over a development proposal to build 180 housing units on the old Sundberg Gravel Pit, which is an abandoned gravel mine, used as an unregulated dump site, located a five minute drive from 11 toxic waste sites. The NIMBYs tend to react to development proposals, don’t have clear objectives for future watershed condition, but are extremely motivated when aroused. They form an episodic communication network, but are not united in philosophy or methods, and core members, through repeated battle, have developed a warrior ethos.

Homeowners and Neighborhood Associations – Gold Crest and Cooper Crest are two HOAs recognized by the city as neighborhood organisations. There are several other Neighborhoods on the eastern periphery of the watershed, but much of the urbanized watershed is composed of disorganized sub-divisions, or unincorporated county, without functioning neighborhood organizations. Some of these institutions own greenbelts or storm water ponds that provide key corridors for water, wildlife, and forest remnants. Many HOA/Neighborhoods have some kind of internal communication network, but don’t have a clear vision of watershed status or future, and may be preoccupied with internal neighborhood politics.

The Trail Builders (sub-culture) – There is a proposed pedestrian trail network that passes through the southern side of the watershed, being developed by a group of well-connected retired professional advocates, with relationships in state and local government. These advocates are using their networks to incrementally build a regional pedestrian and bicycle trail system that will connect the State Capital to Capital Forest on the SW edge of the greater Olympia city-state.

Religious Institutions – I have heard bits about four religious communities that reside around the edge of the watershed: a Catholic parish, a LDS Temple, a Baptist Church, and the Unitarian Church. The LDS and Baptist leadership appear supportive of the trail builders, and the Unitarian Church has an earth stewardship group that has offered their facilities for public meetings to support watershed restoration. There are other potential religious communities that I have not explored. Each religious institution manages a communications network within its membership–it is unclear to what extent each of these institutions have a city-wide draw, or represents a more local population.

Olympia Coalition for Ecosystem Preservation – a small alliance of professionals advocating for protection and restoration of ecosystems in the vicinity of Olympia, currently focused on the westside green belts along Budd Inlet, but also interested in continuing to develop their capabilities. There is some relationship between members of the Coalition and both Evergreen and St. Martins colleges, and other regional restoration workgroups.

Sound Native Plants – A regionally known native plant nursery and restoration contractor lives in the South of the watershed, and has a wealth of experience and skills, but needs to survive through more or less continuous contracting, but has a community-oriented world view and has supported local work in the past.

Thurston County – Under the Hirst Decision a county was sued for allow development without knowing the status of groundwater. Thurston County is now responsible for evaluating the groundwater status of the watershed under new state requirements, and has regulatory jurisdiction over half the watershed. The county has a fish passage program that is seeking to avoid inaction in the face of legal liability under tribal treaty rights. There are two fish passage barriers in the lower watershed that appear to be affecting spawner distribution. The county led a watershed planning process 20 years ago, that set targets for forest cover, and warned of damage to the watershed from development that has been implemented in some ways, and neglected in others.

Farmers (sub-culture) – We have contacts among a scattering of crop farmers and grazers in the watershed, mostly clustered on the SW corner of the watershed, grazing goats, and running organic community-supported agriculture or intensive vegetable production operations. They are generally supportive of ecosystem conservation, have knowledge, skills and equipment, and also need to use a large portion of their land and labor for commercial food production to make a living.

Farmers (sub-culture) – We have contacts among a scattering of crop farmers and grazers in the watershed, mostly clustered on the SW corner of the watershed, grazing goats, and running organic community-supported agriculture or intensive vegetable production operations. They are generally supportive of ecosystem conservation, have knowledge, skills and equipment, and also need to use a large portion of their land and labor for commercial food production to make a living.

Thurston Conservation District – The CD is a county-wide “special purpose district” with a budget based on parcel assessments, and staff that administer technical assistance and cost share programs, particularly to farmers, but also to private land owners, to solve ecological problems. They also run a environmental education program in schools focused on water quality monitoring (South Sound GREEN), but don’t have a particular presence in Green Cove. The District has been under assault from politically conservatives that think that the CD should be only be providing farmer subsidies, and not participating in restoration.

Veterans Ecological Trades Collective – A growing network of veterans, now based on a new farm in south Thurston County, organized around permaculture principles, are seeking to develop skills and land access for veterans, in fields related to forestry, farming, and ecosystem management. They may enjoy practical training opportunities.

Capitol High School – A 15 minute walk from Grass Lakes, the high school has a greenhouse, a horticulture program, and an environmental club. The cross country program may use trails in the park once access is increased by the Trail Builders.

South Puget Sound Community College – similar to Evergreen, SPSCC has internship opportunities, a horticulture program, and a natural resource science offerings, and may more more organized communications networks than Evergreen, and is located in the adjacent Percival Creek Watershed.

Blue Heron Bakery – A local restaurant and cafe on the south edge of the watershed that has offered using their space for community events.

South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group – a regional fishery enhancement group, SPSSEG has project management capability for in-stream work and assessment, and is completing a habitat assessment of Green Cove Creek using state grants.

Bark and Garden Center – the largest retail ornamental nursery in Olympia, serves the gourmet gardening community of Olympia. They don’t have a workshop schedule, and their communications network is unknown.

Master Gardeners Foundation of Thurston County – a network of gardeners that host workshops and provides 40-hours of detailed ornamental garden and integrated pest management training in exchange for 40 hours of volunteer community services. Master gardener graduates are looking for volunteer opportunities.

A Vision for Three Capabilities

Plainly, an “Ecosystem Guild” of sorts exists in the watershed, but it is fragmented, doesn’t have shared ecological goals, and lacks the capabilities necessary to restore and protect the watershed. Many individuals are overburdened, or missing specific resources to realize their hopes and visions. There are multiple social networks, but very little local place-based ecological knowledge in circulation. There are tangible pools of capital that are underutilized. Ecological work is limited in scope and fragmented.

I propose a set of three future conditions that describe our ability to achieve an educated community capable of protection and restoration:

EDUCATE!

- Transparent – the state of the watershed is transparent to each resident.

- Free Knowledge – The knowledge and skills necessary to protect and restore ecosystems are available to anyone in the watershed that is willing to apply effort toward watershed restoration.

- Self-aware – The watershed community can generate accurate knowledge of watershed condition.

To protect and restore, a watershed community must have knowledge and skills. When a watershed community can all plainly see the condition of the watershed, and answer its own questions, and has the skills and knowledge to act, then a community can begin to protect and restore in earnest.

PROTECT!

- Proactive – residents anticipate impacts, and can work to increase protection prior to a crisis.

- Efficient – the processes and tools necessary to address threats are ready and at hand and do not excessively drain resources.

- Accountable – the inability of local governments to provide ecosystem protection are remembered and addressed at the ballot box.

When an educated watershed community understands the character of threats, and has proactive strategies and resources in place to either immediately counteract threats, or pursue redress over time, then a community can protect a watershed.

RESTORE!

- Self-reliant – The community has the institutions, knowledge and skills to design and implement restoration of the water, biomass, and diversity.

- Integrated – Restoration efforts are part of the economic and cultural life of the community, and provide multiple benefits.

When a community that is able to protect its resource base has the resources to design and implement restoration, and when that work comes naturally and is socially fulfilling, than a community can restore a watershed.

A Strategy

We need a strategy for developing these three conditions and capabilities. Of course we can refine our destination over time, but it is important to start heading somewhere if we don’t like where we are. If we can support meaningful learning through meaningful work we can be very efficient and effective. I propose a mix of 1) on-line guild-generated educational content, 2) coupled with project-based “open consultancy” teaching, and 3) a flipped classroom model for connecting skill building related to the project work. This approach will likely require a “collective impact” approach among watershed partners, and the development of some “backbone functions”. Lets break that down:

The best example of a user-generated content platform is a wiki. The Salish Sea Restoration Wiki provides a framework in which anyone can contribute and organize content. This framework can incorporate both open-source content through an archive, and proprietary content through links. Wiki links are stable over time. This kind of open-source repository becomes an open archive and reference manual for our work. Project after project, site after site, watershed after watershed, you can easily refer back to continuously improving wiki content, rather than republishing resources, evidence or materials.

An open consultancy using continuously improved standards is where a professional provides a consultant service to a land owner or manager, to design and implement restoration or protection efforts. Unlike private work, the open consultancy solves a problem by teaching a group of students and the client to do the work through sharing standard methods (documented in the public domain on the wiki). The professional builds intellectual and experiential capital in the community, while generating a protection or restoration product, while further refining shared standard methods through the interaction. The client gets a product, and diverse views of the problem, while learning the methods by which they can adaptively managing the site over time. The student gets to immediately exercise and test new knowledge and skills in a practical context. Consultants, students, and clients contribute to improved standards through the process of doing work.

The flipped classroom model is where a student is taught knowledge through on-line reading or video, so that workshop and field time is reserved for experiential skill development and getting the work done. This allows the student to control the pace of knowledge transfer, and puts responsibility back on the student, for fully engaging in the open consultancy and ecological knowledge. A flipped model standardizes the knowledge available to students and clients as they enter the open consultancy, regardless of the consultant running the project, and reduces the cost and effort to the consultant, maximizing the value for everyone involved. By coupling the flipped classroom with continuously improved standards, everyone involved in a project becomes more effective over time.

Needless to say, we are not there yet. Neither the shared restoration and protection standards, the skill and knowledge base, nor the self-study resources, exist in the public domain. In addition, consultants with the technical knowledge to restore and protect, usually lack skill as teachers. The carriers of knowledge and skill (among agencies, NGOs, and private contractors) have typically not organized knowledge for efficient transfer, nor are they motivated to do so. This work is delegated to academic settings that typically lack practical experience. We do have substantial knowledge about the watershed, but lack detail. The professional restoration system, holds tremendous knowledge in private contractors, who sell knowledge and skill at $100/hour, which watershed residents can never afford. Institutions that do environmental education, don’t invest in skill development or information storage and retrieval, and depend on a direct instruction model for sharing knowledge (which has a low up-front cost but doesn’t generate a durable and retrievable resource). Environmental educators working with the general public rarely have the confidence or experience to run an open consultancy. Researchers typically lack practical experience in manipulating systems. Public agencies, which have a public benefit mandate, are overburdened or lack a shared strategy, platform, or motive for making knowledge transferable and empowering residents in protection or restoration.

So we have all the bits and pieces present in Green Cove, along with a huge concentration of industrial resources, but we are not organized into a functioning system. I believe there is an opportunity to develop a model system in Green Cove, in collaboration with local and regional partners.

To not get lost in discussion, and get to work, we need sites where we can start to experiment with open consultancy.

I am aware of four potential landscape sites at different scales and with different functions that could serve as a test. There are many other potential sites beyond these, but each of these landscapes has an existing protection and restoration stewardship community, and an immediate opportunity to conduct a consultancy:

- Kaiser Wetlands private conservation lands (site-scale restoration)

- The Marshall Middle School (site-scale nursery/mother-garden)

- The Grass Lakes Nature Refuge (multi-scale restoration)

- The Olympia urban growth area (landscape scale protection)

The watershed also has a potential student body, including middle school students, college students, neighborhood stewards, and professional and amateur training students. So what kind of situation makes for a good open consultancy pilot site for a startup?

- The land manager is interested and supportive of the model

- There is a discoverable body of students attracted to the work

- The work in not too complex (to reduce the initial burden for standard development and skill training)

- We have guild volunteers willing to serve as consultants

The Guild will need to define an “open consultancy standard” which describes how we coordinate the professionals, interns, and students and bring them into a relationship; and define scope with the land manager, while designing the project to social and ecological context at multiple scales. We will need to outline standard practices for assessment, design, and implementation of restoration and protection work. In some cases we’ll be designing standards as we go. We need to support the consultancy by teaching knowledge and skills, using self-learning materials. We need to understand and align with the cycles of the 8 seasons. We’ll need to efficiently develop lessons on video that students can self-study before field work.

This will take more work than just running a “sage on the stage” workshop. However, I suspect we may be creating much more value over time. Each open consultancy generates cultural capital that supports the next consultancy. In this model the processes of learning, teaching, design and implementation are integrated. You are both doing stewardship and building systems that make stewardship easier.

A Proposal For An Initial Open Consultancy

I believe the best fit to test an open consultancy model would be restoration of private wetland buffers, and development of a mother-garden at Marshall Middle School. As an example, here is how institutions and sub-cultures within Green Cove might be organized to conduct the Kaiser Wetland Work.

Kaiser Wetlands Buffer Restoration

Subject: Patch Scale Stewardship in a Wetland Buffer Forest – increasing infiltration, biomass potential and biodiversity support in a degraded young forest stand.

Target Standards:

- Stormwater Infiltration

- Forest Patch Stewardship

Client: Capitol Land Trust and Affiliated Private Landowners

Consultant: Ecosystem Guild and a Restoration Standards Partnership (potentially including City of Olympia Environmental Services, Sound Native Plants, Native Plant Salvage Foundation, Veterans Ecological Trades Collective, Stream Team, Agency Scientists, Thurston Conservation District, or Capitol Land Trust)

Students: Evergreen Students, Marshall Middle School, Homeowners and Neighborhood Associations, NIMBYs, South Puget Sound Community College, Veterans Ecological Trades Collective, or Master Gardeners.

Backbone

Following the Agile development strategy we need to quickly develop a working prototype. Our first open consultancy will likely be improvised and rough, grabbing resources and methods off the shelf. As we go we will be developing our skill at defining and evaluating a standard. Does is embody good design? Does it integrate multiple scales? Does it describe the range of variation? Should the standard be split or lumped? Also, as we do the work we should be thinking about how each event serves to build the backbone functions that support collective impact in the watershed. Six principles define backbone organization function under a Collective Impact model.

- Maintain clarity of purpose (realign, communicate, co-create)

- Drive long-term momentum and growth (partner raising, build community, strategic partners, recognition, autonomy, ROI narratives, conditions for innovation)

- Build Partnership Identity (formal launch, rituals, team-building, work in and on partnership)

- Connect and Align People and Activities (conscious integration, map skills, define domain and role, good meetings, accountability, build memory)

- Involve the Watershed Community (understand needs, focused co-creation, engagement, agile development,

- Measure and Learn (critical metrics, data stories, find problems)

Building on these backbone concepts, I propose two workshops. Timing and location depend on community interest. To reduce workshop cost, we would test a modified “open space technology” standard, where both the summoning query, and elements of the open space deliverables are more deeply defined in advance. These two workshops would directly reinforce the open consultancy model, and strengthen the consultant community.

- Regional Revegetation Standards Retreat – NGOs, local governements, Conservation Districts, Tribes and Conservation Corps conduct revegetation all over lowland Puget SOund. We would benefit from developing shared standards for assessment, design, installation and monitoring of projects so that we can improve our efficiency and effectiveness. This retreat bring together interested parties to establish a revegetation section of the Salish Sea Wiki, and initiate information sharing among revegetation workgroups.

- Green Cove Watershed Retreat – This workshop would bring together individuals from among the institutions and subcultures described above, to explore the development of backbone functions for the Green Cove Creek Watershed.

But What About Restoration Camping?!

I did want to briefly mention that I have not forgotten in any way about restoration camping. What I believe that I am described above is the social context for restoration camping, which is essentially a sequence of open consultancies, delivered through a mobile field camp. One step at a time.