Plant-soil work is perhaps the fundamental process of ecosystem stewardship. Every landscape on earth is shrouded in a green cloak of vegetation, with a particular structure and composition. Plants created the earth as we know it. The line between plants and soils is difficult to draw. Plants are a manifestation of a living soil ecology, and the soil ecology is aggressively modified by plants. We almost always work on both together. This land cover drives hydrology and carbon storage, and is the infrastructure of biodiversity.

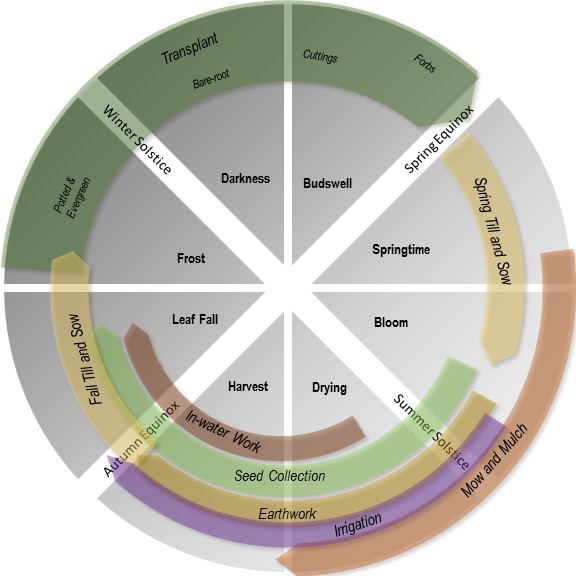

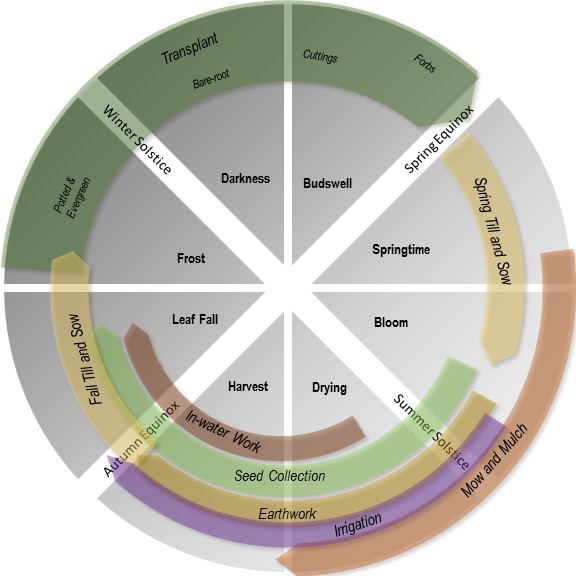

Like most human endeavors, our work with plants and soils follows the annual cycle of the sun. The Eight Season Year is a framework for organizing that annual cycle. Plant-soil work occurs everywhere locally; a primal intersection of social and ecological systems. Some kind of multi-scale systems assessment is useful for clarifying the context of plant-soil stewardship. Our work has layers of purpose and meaning.

Plant-soil work is infinitely varied, but follows recurring patterns. Buried in tradition there is some goal of achieving a desired future state. If you are farming for a living, that desired future state is an easy to harvest field full of product you can sell. If you are cultivating an ecosystem, your desired future state may be an evolutionary trajectory that plays out over 1,000 years. The important part is that you know where you want to go. Without clarity about where you want to go, you cannot pick a target, assess a complex social-ecological system, or design a good soil-plant treatment to get you there.

Most soil-plant treatments are built of three parts: 1) disturbance, 2) propagation, and 3) aftercare. This is a simplification, as a “treatment” may include several cycles or repeat steps, but we can always find three parts:

- Disturbance – Vegetation fills every viable niche on the surface of the earth. To introduce a new vegetation pattern we apply some destructive force, to create a vacancy. Nature does this with floods, landslides, fire, and herd animals. Humans use tillage, mulch, animals or poison. As part of our disturbance we may modify soils, changing their structure and composition. Because disturbance takes work, we constantly ask, how little disturbance is necessary to create enough of a vacancy to achieve the desired state?

- Propagation – The second step is to introduce some propagule into our vacancy. A propagule can be seed, a cutting of stem or root, a bare root plant, or potted stock. Perhaps we are only activating seeds sown in the seed bank by previous generations. The production and transport of propagules takes work, and less developed plants are better able to adapt to a new niche, but less able to withstand stress. So we constantly ask, what is the smallest propagule that can establish on a site, and initiate the transition to our desired state?

- Aftercare – Once our intervention is complete, the wildness of the earth re-asserts itself over the site. Propagules are subject to competition and stress. We mediate that process, by supplying nutrients or water, or with selective disturbance. Aftercare is always more expensive than the initial disturbance, because we have to work around our propagules. We now pay for any poor choices in steps one or two. There are many risks: poor site assessment, ill-informed species selection, too little disturbance, too small a propagule, a labor intensive layout, a bad season, poor quality stock, or unskilled planting. We pay for any weakness in design with aftercare. If our design is poor, or we are unlucky, we can fall into spiraling aftercare costs, or fail to achieve our desired change.

Every plant-soil treatment successful or not, emerges from a vision of a desired future state. In restoration, we push ecosystems from one wild state to another wild state. Given the complexity of wild things, lack of clarity in design is not surprising. What exactly is the desired change? Where are we going and why? It is easy to be lazy in our intentions and purposes, and play it by ear. I suspect that if we are going to restore hydrology, carbon stores and biodiversity at the scale of watersheds, our soil-plant work must become a disciplined art. This art is built from a deep knowledge of place, species, tools, technique, and the annual patterns of vegetation.

Evolved vegetation is not entirely random. What we see in a plant community are the results of forces at work in a place. Those forces precede us and remain after we leave. Vegetation ecologists attempt to explain the factors that control vegetation, and their theories can help us organize our thinking about soil-plant work, so we are working in alignment with ecological drivers. In particular we pay attention to the role of disturbance and stress. These drivers change as a stand recovers from disturbance (a pattern called “succession”), and different species have traits that are adaptive to circumstance. However the evolution of a patch of vegetation is also affected by more random processes of assembly, like who’s there now, and who shows up next. The narrative of vegetation is like an story where the details change, even as the themes remain the same.

Lets take each of these concepts in turn:

Disturbance

Each site has a regime of disturbance. Disturbance involves physical damage to a plant. Storms rip at stems and leaves with some combination of wind, ice, snow, and cold. The flooding of rivers and streams can scour or bury, and saturated slopes slump and slide. Grazing herds nip and trample more noticably than the quiet predation of insects or fungi. Living under a big-leaf maple insures an annual burial under smothering leaves. Plants have a traits that make them more or less resilient under disturbance, such as winter retreat to roots, stems that form roots, or the production of toxins. The frequency, predictability, intensity, and homogeneity of disturbance determines who lives or dies on a site, and shapes structure and composition.

Stress

Optimal growth is achieved in warm, moist, and oxygenated environment in the presence of nutrients. In the absence of stress and disturbance, life in a patch of vegetation becomes a race for light amid rampant growth. As growing conditions become less than ideal, this causes stress, a reduction and eventually cessation of growth. Cold, heat, prolonged inundation, nutrient deficiency, or drought can slow growth or force dormancy. Each species has traits that make them more or less resilient to different stresses: waxy leaves, deep roots, or symbiotic relationships with bacteria or fungi. As with disturbance, stress comes in different frequencies, intensities, and with variable predictability over an annual cycle. Species that are resilient to the stresses of a site will come to dominate the vegetation.

Succession

Following a severe disturbance, there may be more resources available to an entrepreneurial propagule. As vacancies are filled, and the annual regime of stress and disturbance settles in, the rewards for exuberance decrease. Even as the work of plants increasingly moderates climate, retains moisture, and cycles nutrients, those resources are shared among increasingly entwined co-habitants. The species that are successful after disturbance shift over time, from fast growers, to those that are able to thrive under the stresses of cohabitation. This process is called succession, and as plant-soil workers, we can anticipate, accelerate, arrest, or reset successional processes to suit our purposes.

Assembly

While we can talk about pattern, the reality of vegetation is formed by uncountable individual experiences by individual plants. Any pattern we might detect emerges as a general direction, driven by a mix of potentially erratic processes. While succession is a tidy and useful story, the development of vegetation does not follow a predictable path. The sequence of arrival, specific interactions, and random events may create unexpected changes in the story-line of vegetation. Under climate change, past performance may not indicate future behavior. As short lived species, we humans may have a very limited understanding of long-lived cycles and patterns. We may find patterns out of habit, to soothe our confused minds, while the wild is sublime in its chaos. It may be more useful to see evolving vegetation as subject to a variety of filters that winnows down the pool of potential species, to those that can complete the challenge of life in the moment. A variety of young ideas, under the umbrella of assembly theory, attempts to makes sense of emerging unpredictable reality.

Annual Cycle of Work

Armed with this language, lets walk through the Eight Season Year beginning in Springtime (early spring). Bud-swell (late winter) is a culminating flurry of activity, when woody plant propagules are inserted into a site during cold weather dormancy. In Springtime we catch our breath, and look at what we have done. We anticipate our our past mistakes, and begin aftercare and disturbances in preparation for the next planting.

Springtime (Equinox)

By the equinox, all our woody planting should be complete, and we can turn our attention to aftercare of old plantings, and disturbances to prepare for new plantings. We can observe leaf and shoot development rate and color, and get a feel for which plantings are robust, and which are weak. While the ultimate outcome is yet to be seen, and first year growth varies among species, we begin to feel which of last years treatments are effective. We get to see the regrowth in last years disturbances, and the level of competition. Any detail weeding should be done in spring time, before weeds are rampant. Tillage windows become abundant, although spring seed beds will be rougher than those begun in fall, and seeds are sown when not requiring cold stratification.

By the equinox, all our woody planting should be complete, and we can turn our attention to aftercare of old plantings, and disturbances to prepare for new plantings. We can observe leaf and shoot development rate and color, and get a feel for which plantings are robust, and which are weak. While the ultimate outcome is yet to be seen, and first year growth varies among species, we begin to feel which of last years treatments are effective. We get to see the regrowth in last years disturbances, and the level of competition. Any detail weeding should be done in spring time, before weeds are rampant. Tillage windows become abundant, although spring seed beds will be rougher than those begun in fall, and seeds are sown when not requiring cold stratification.

Bloom (Mayday)

Bloom is the peak of above ground growth, and the moment when new plantings are over-topped. Vegetation is succulent, nutrient rich, and easy to cut. This is the opportunity to chop and drop, or cut and carry material to smother planting sites for next years growth, and to protect new plantings from drought. The mechanisms for providing water as aftercare should be in place, as drought can come in bloom, and water may be most effective if applied in occasional deep irrigation before drought stress arrests growth, so that new plantings can sustain root growth into the drought. In bloom, the flowering details of species are easily observed, but spring ephemerals are still present.

Drying (solstice)

Earthwork and tillage is easier while there is still some moisture in the soil. After the rush of cutting and piling and before the heat of summer is the ideal time for all outdoor construction and earthwork. Building trails and bridges. Cut and carry can continue in moist areas with rampant growth. The seed formation and collection season has begun.

Harvest (Harvest)

By Harvest, the natural dry-down may create intense stress. In new plantings, some of this stress is beneficial, driving plants to commit to deeper roots. Seed harvest is in full swing.

Leaf Fall (Equinox)

With the return of rain, the aftercare season is over, but planting season has not yet begun in earnest. This is a good time for starting a new round of layering.

Frost

Frost is the beginning of the dormant season, and the ground is less likely to be frozen than during darkness. Out-plantings, particularly evegreens, will have the maximum time to adjust to their new settings.

Leaves are abundant, and can be collected, moved, stockpiled or concentrated to achieve disturbance effects. Some municipalities will stockpile or even deliver leaves. Tree services begin their winter storm cleanup work, and will be motivated to dump ramial chips.

Darkness

After a flurry of planting in frost, and after the holidays, attention turns to cuttings, which benefit less from the early out-planting. Clear days bring frozen ground, and inefficient planting. Bare root orders arrive, having been dug by nurseries during Frost. Planting in Darkness makes you wonder why you didn’t get your work done during Frost.

Budswell

As day length expands, buds begin to break, stimulating root growth. Elderberry and osoberry pop first, and any bare root plant or potted stock must go in the ground or be replanted into nursery beds for another summer of watering. Weedy root-mass not sufficiently damaged by disturbance will start to push through rapidly decomposing mulch. Leaves and cuttings from last season are almost gone, while wood chips persist. This is the flurry, before you take another breath, and switch to aftercare and a new wave of disturbances.

Each plant-soil treatment is an experiment, based on a prediction (sometimes unstated or unclear). To the degree each treatment is well-designed, and we watch our results, we can advance a shared art.

Our greatest challenge is to find and let go of useless work. Can we use the right tool, and the right technique, at the right time, and create the desired result with less effort? Can we create a sequence and structure and timing of disturbance that also reduces the labor of aftercare? Can we use accelerated assembly and succession to let time do our work for us? This is the mystery ahead.

Right now, I suspect our plant-soil work is rudimentary. We are good at trees, because they are easy. Biodiversity is harder. Succession is haphazard. The dynamics of assembly, mysterious. We use lots of oil and buy lots of stuff. Labor is separate from design, and monitoring is generally absent. Staff turnover is rapid, and plant-soil workers are the last to be consulted and the least paid. We don’t respect the art.

Further, most of us don’t use wild plants, and so we barely care about the wild communities we tend. A young forest with fifty species might provide twenty products to enrich a community, and harvest might be just another tool to guide assembly. But we are divorced before the planting is even done. The designers have gone home, and the crews toil in the rain, and may never see the site again. No wonder we remain ignorant.

The cycle of the year suggests a web of practical skills from ecology, horticulture, ethnobotany, pedology, phenology, silviculture, agriculture, botany, allometry, biology, agroforestry, and culinary arts. You can follow the roots of these sciences deep into time before memory. Each thread of this web ties us to the land. Each place is a new story unfolding.