Infrastructure (n.) – the basic physical and organizational structures and facilities needed for the operation of a society or enterprise.

We cannot build a regenerative and just bioregional culture without reinventing our infrastructure, because our infrastructure defines our relationship to ecosystems. Humans are “ecosystem engineers”—we reshape ecosystems to enable our society. Then we depend on what we have built. Infrastructure starts out as a good idea, and then we come to depend on it for survival.

100 years ago there were few cars, fewer parking lots, no interstate highways, and the rest of the oil infrastructure barely existed. We ran a world built around steam engines and horses. Our use of energy, time, and land revolved around these historical infrastructures. Everything always has been and always will be an ecological system. But when we create infrastructure we seem to believe we are above nature. We don’t acknowledge that we are just shaping our nature and our relationship to the earth, for better or worse.

Infrastructure is the warp on the loom upon which we weave our daily routines and build a society. Our houses are made of forest fibers, bound with metals, smelted from ore wrested from the earth by machines. We are connected by pipes, wires, and ribbons of asphalt to sustain the flow of food, water, fuel, and waste. The whole construct, from industrial forest to mine to household, is driven by fossil fuels.

In our current state, we have become collectively oblivious. Yes, there are interest groups that are very aware of our infrastructures. But the choice of what to regenerate and what to produce is not a subject of popular discourse, we are deep down paths chosen by our ancestors. And how we live and who chooses how we live is not on the table.

What we have built is a system of infrastructures that defines how we live, and how we relate to each other. Our cities and towns seem like home, but they are dead zones. They receive resources and produce wastes and cannot keep us alive. Urban soils are mostly damaged or paved. Water is poisoned and the summer brings drought. 65% of the population is completely dependent on supply lines they don’t control, and most are unable to produce food or shelter in any substantive way.

The infrastructures combine with a system of ownership to both enable and define social-ecological systems. We are born into these systems, but the towns we live in are just the belly of the beast. Far away, the extractive maw chews away at industrial forests, grazed deserts, and eroding prairies, suckling hungrily at depleted aquifers, or ripping into the earth hunting for rare elements. In many cases, this extraction is greased with human blood. You don’t see extraction zones when seated in our nest of infrastructure. You can’t see the whole story strolling down a suburban street.

Having built this infrastructure, we give it to our children, along with all the attendant stories, rituals, beliefs, and taboos. This gift has consequences—it shapes our hopes, expectations, and fears, and determines the future of the biosphere.

At 7.53 billion, this inherited infrastructure is what keeps us alive—drinking clean water, eating food, and staying warm. In an earth with no ecosystem beyond reach, we are the beneficiaries. We ride the beast. This infrastructure is now required—it is our ecological niche. We no longer evolve in response to the stress and disturbances of our environment. We just use more energy to change our environment.

Through infrastructure, our genetic evolution has been eclipsed by cultural evolution, and a culture is bound to its infrastructure. Our evolution has thus become untethered from an ecological conversation. We are the self-absorbed boors at the gathering of the species. We only talk about ourselves. Sitting more alone every year, we just need to sustain our infrastructure, forever.

The problem is that the infrastructure we’ve inherited is a Ponzi scheme. Our infrastructure burns ecological capital. Even before climate change, we drained water from underground reservoirs, our soils are a little weaker each year, our river deltas a little more polluted with nitrogen, and our global forests a little younger and smaller. A few of us get to ride in style, but overall, the colonial-industrial vehicle is a disaster. Each generation makes its profit by stealing from the next, and everyone feels rich, until the well runs dry, and the fragility of the underlying apparatus is made bare.

We are conditioned to attend to numbers that have no bearing on this reality. Gross national product and capital accumulation only reflect profits skimmed off a system of declining ecological production. We measure and trade labor surrogates, all leveraging energy slaves. Like that narcissistic boor mentioned above, we measure all our activity, as if it were the foundations of life. We value destruction as much as creation as if our activity were the only thing of worth. To a large extent, our financial measures of capital ownership just describe our relative social positions inside the cultural machine and don’t measure the health of the machine itself.

And our cultural machine is largely made of infrastructures–poorly understood, rarely discussed, and usually controlled by someone else. We wouldn’t know how to change, even if we had the will. But now, more than any other moment in history we must choose. Whatever social or political future we can muster, it must involve building a new infrastructure, that lives in harmony with the earth. Any social or political system that cannot do this work, is deficient.

Not all infrastructure is made equal. Consider a well-designed biodynamic farm, where pastures feed cows and horses, which in turn work smaller crop fields that sustain a settlement. The tapestry of woodland, pasture, field, and household is a whole creature, and if rightly proportioned, the soil is richer every year. An industrial corn and soybean rotation also produces a yield of food, while degrading the soil and undermining the climate. It requires only one operator over thousands of acres but is dependant on industrial equipment and colonial supply lines, petrochemicals, and uses nutrients mined from rock and extracted from the atmosphere by burning natural gas. It is soaked in fossil energy. The second the flow of fuel stops, the well dries up, or the soil dies, the system breaks down. Now as we sit on the edge of global ecological collapse, we can take a good look at this package we are giving to our children.

Thinking About Infrastructures

We have lots of choices that we almost never make. What system shall we build for our children? These kinds of choices are too much work, too inconvenient, someone else’s job. Being creative about something like a cultural ecology requires not only massive self-discipline and effort, but demands a framework–some kind of scaffolding upon which to organize and elevate our thinking. Here are three tools that help us start:

First, we can recognize that everything we can see is our ecosystem—a collection of living and non-living components forming relationships. The parking lot in front of my condo is an ecosystem. It does a horrible job cycling energy, nutrients, or water, and is generally hostile to life. It requires constant application of energy and toxins to function and mostly generates heat and subtly poisoned water, but it is still an ecosystem. I admire any creatures that can survive there because it is designed to be dead. It’s twice as large as necessary, but that is what makes it convenient to drive in.

Recognition is not easy. Our conditioning is the unseen part of our inherited infrastructure package. We are trained to think of that parking lot as somehow a separate project—somehow apart from the living earth. But we took that land from its previous inhabitants for our exclusive use. It’s called colonization, and it’s not just a period in a history book. It is a way of life. That parking lot is a degenerate thing we created because we wanted it all for ourselves. Only when we take a step back and observe our whole landscape as an ecological system of our own creation can we start to break the conditioning that makes it seem normal. The conditioning makes the familiar seem normal, as the character Morpheus says to Neo in the movie The Matrix: ”You take the blue pill, the story ends. You wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe.”

So first: we must see the ecosystem that we are conditioned to not see.

As a next step, we could benefit from thinking about infrastructures as plural—as made of many diverse elements. We have enterprises within enterprises and they require different structures and facilities. Our cultural orthodoxy presents “infrastructure” as a singular monolith, the sum of all that is necessary to perpetuate this peculiar colonial-industrial society. Decisions about our infrastructures are generally reserved for “leaders” while the consumers of infrastructure are thankful but generally ignorant of the details. This asymmetrical flow of information is part of the package, a package with layers of social inequity entwined with hierarchies, from families to schools to businesses and governments. We are surrounded by a multiplicity of interconnected alternatives—we are just unable to notice them. Our infrastructures are both interdependent, but also separable. Training children in schools doesn’t require an electrical grid, and water supply doesn’t require sewers, but if you don’t learn about waste management or energy systems in school you can’t see the alternatives.

Third and finally: we can learn how to organize biological systems as among the most elegant of all infrastructures. We live in a verdant coastal temperate rainforest. For a well-adapted society the forests, beaches, wetlands, and rivers are all valuable infrastructures generating food, water, shelter, and energy. They are self-organizing and self-repairing—autopoetic. To a society that has become addicted to fossil energy, annual tillage grain production, and the global transport of materials, our infrastructures are complicated, fragile, expensive, and dangerous.

Everything we build immediately begins to break down. Only biological systems have the potential to regenerate, to be self-organizing, and to grow over time. Most of what we actually need to sustain our lives can be created and maintained locally in biological systems–food, shelter, and water. Only our information, transportation, and energy infrastructures necessarily operate at larger scales. It may be energy, transportation, and communications that ultimately define colonial-industrial civilization, because they allow us to ignore local biological infrastructure, in favor of parasitizing somewhere else.

Three simple ideas: everything is an ecosystem, we maintain a smorgasbord of infrastructures, and biological infrastructures are our only viable foundation.

With these reflective lenses firmly attached, we have some of the scaffolding that might let us make sense of ourselves. We are ecosystem engineers, and everything we think, see, and use defines the ecosystems that we create. We have a heritable culture, and that heritage is both physical and social. Those infrastructures most necessary for survival are local and biological, while those that define colonial-industrial civilization operate at larger scales. Our inheritance is complex with choices that are hard to change, and we have a natural sentimental attachment to the infrastructures given to us by our ancestors. Our ancestors bequeathed us a death trap.

Infrastructure Is What Infrastructure Does

With conditioning comes blindness–once we believe something to be true we stop seeing. Once we have tools that enable a way of doing things, we forget that there are other ways to do the same thing. To assess and evaluate our infrastructures, I like to reframe them in terms of what they allow us to do. Our infrastructures are valuable because of what they enable us to do. They are embodied processes. Each infrastructure is a productive response to a perceived problem. It is this generative capability that makes them powerful. We talk about infrastructure as if they were structures, but their essential capacities are how they facilitate processes.

The core infrastructures of human societies operate as extensions of biological ecosystems and can be evaluated using ecological thinking. Like all ecological processes, our infrastructures either transform or move matter and energy—transformation or flux. To understand or design an infrastructure you need to track the form and flow of matter and energy. Only when we start to evaluate our infrastructures as ecosystems can we start to see where our troubles begin.

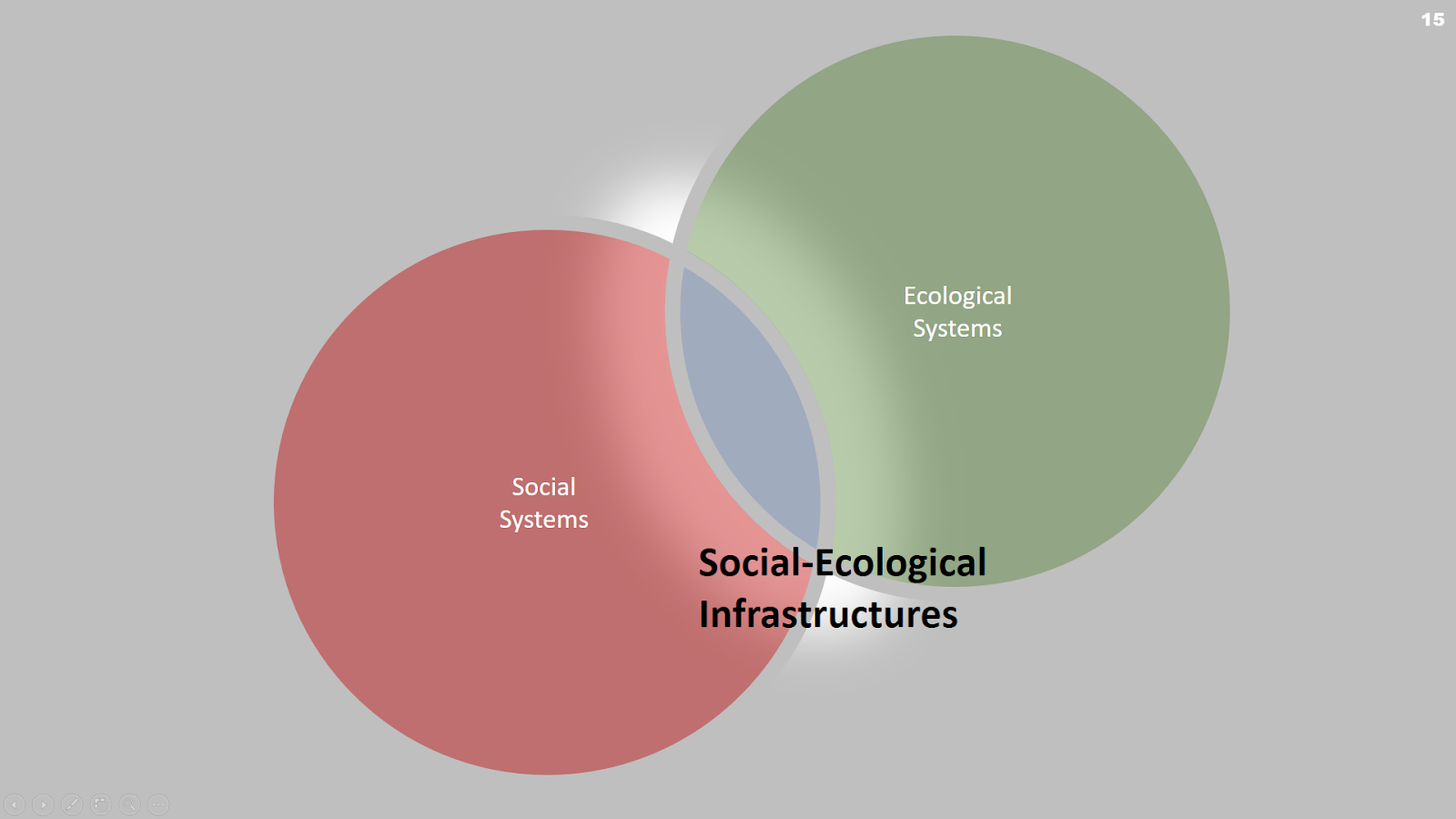

When infrastructures facilitate social and cultural processes, our thinking gets muddy. Redesigning ecological infrastructures will likely force us to wrestle with our social infrastructures, but let’s not yet take our eye on the ecological ball. A philosophy untethered from ecosystems is dangerous, and we have been untethered for generations. We know our systems of power and ownership are entwined herein, but surviving this game requires we play for ecological survival, and loaded down with philosophical baggage, we are likely to play poorly.

Between the ecological artifice of colonization and our conditioning, we can no longer see our ecological infrastructures. One of the qualities of a narcissist is that they are preoccupied with their self-conception. When we think only as individuals we are easily confused. The “individual” is not the scale of biological organization at which to understand infrastructures, survival, or for that matter much of anything. For 200,000 years we have functioned as households, settlements, and networks of settlements. To think about infrastructures we must strip away a bit of our self-absorption and may benefit from some language to help us anchor in the structures of society.

For the conversation, we need shared language. For most of history, people have found security by forming households and networks of households. Our closest relationships are among those who share shelter. Settlements are clusters of households where we sleep, eat, work, rest, and play. Production sites are places we go to work in the ecosystems to meet our needs. Household production is where we meet our needs within a household, and usually close to home (unless we develop a nomadic infrastructure). Community production is work where many households gather and then distribute goods in turn to many households, usually through elaborate exchange rituals involving currency.

Settlements are nested within settlements, and civilization is by definition the formation of settlements too large and dense to meet their needs through local production.

This kind of simple language can make the structures and processes of the human ecosystem more apparent. Seeing ourselves and our acquaintances as individuals in households in nested settlements, and being able to see a landscape pattern of settlements and production sites, helps us think about how we solve the problems of staying alive. It also helps us look at how our infrastructures have come to function. This is particularly important if we aim to survive on a degraded planet as we simultaneously upgrade our expensive, fragile, and degenerate infrastructure.

So what are the building blocks of infrastructure? Both household and community production require water, materials, and tools. Shelters are essential and durable cultural artifacts that moderate weather and climate. Our shelters define our settlements. Roughly half our energy is used in the operation of our infrastructures, while the other half is spent building and maintaining our shelters and tools.

Infrastructures enable ecological processes. They enable us to create a flow or cause the transformation of energy or material. Our infrastructures are a response to a problem.

As our energy sources became profligate our designs became sloppy–untethered from ecological energies. We started developing infrastructure without regard for efficiency. We wove a vast teetering tower of flows and transformations one on top of the other, all requiring energy. Through this process of stacking infrastructures on top of infrastructures, we have created a huge teetering superstructure. It is difficult to comprehend, particularly when the operating manual is encoded into a hierarchical culture, where we are strangely disconnected from ecological processes.

Why step so far back and take in this view? As we sit on the edge of global ecological collapse, it seems wise to take a good look at this package we are giving to our children. How can we make sense of the changes we need to make? Do we wait for our “leaders” assuming they are less confused than we are? They are not. They are acting out roles they inherited, roles built around a failing system of infrastructure. You can notice that many of our institutions are unable to even consider the meaning of global ecological collapse, and cannot comprehend an infrastructure other than the one we have. The endless reproduction of our existing infrastructure is hard-coded into our cultural niches. For the challenge we face, we have constructed no job to do the necessary work.

Lodged in this teetering house of cards, it can be difficult to recall the base of the tower—those essential problems and infrastructures that keep life from death. It is difficult to innovate if we cannot see the heart of things. Unable to see, we are prone to rearranging deck chairs—shuffling around aimlessly, doing the things that our parents did.

Here is a list of problems that appear to be at the nexus of life and death, using the simple language introduced above:

- Provide drinkable water for settlements

- Provide enough water to production sites

- Tend production site tools and shelters

- Move materials from production sites to settlements

- Assemble materials into new shelters and tools

- Cultivate and harvest food

- Store food between harvest and consumption

- Process and cook food

- Convert organic waste to soil

- Return wastewater to the water cycle

- Gather or produce fuel or energy

- Transport ourselves around our settlement and production landscape

- Move materials and products within and among settlements

- Care for the infirm

- Minimize the impacts of disease and trauma

- Strengthen the capabilities of children

- Introduce youth into creative roles

- Evolve our allocation of roles among members of a settlement

- Design, build, and keep up our infrastructure

This list is not definitive or complete. These problems could be lumped or further split. In less energy-intensive societies that live entirely on photosynthesis, these technologies are woven together into daily, seasonal, or annual rhythms. Each requires both social and ecological components. These problems can be solved at different scales, in different ways, with different implications. Our unique solution set is the operating system of our society. This is the list that matters when the earthquake comes or when we change the climate.

Some of us solve some of these problems in our daily work. A few generations ago, most of these problems were solved at the scale of a settlement or network of settlements. Now many of us have no connection to the solution set. Either we are preoccupied with “more important affairs” or we are providing household services to those that do. We may assume someone is paying attention to the fundamental health of the system.

Let’s consider for a moment the implications of the last bullet on the list of problems—the work of keeping up our infrastructures.

Infrastructures with their ecological and social dynamics are not neutral actors in a society. We spend effort solving problems of our own creation. Before I became an information worker in a vast bureaucracy, I used to work on infrastructure #5, assembling materials into new shelters, where I specialized in building soils, growing plants, and building small walls, paths, and fences. A significant part of my labor was to undo the damages caused by the construction of the shelter or the surrounding transportation system or to satisfy aesthetic rituals for households too busy to tend their own land, who never learned as children, or who had the social status to have me do work for them.

Now I work as a restoration ecologist. I spend my effort trying to undo the damage to the biosphere caused by our production sites and transportation systems. Infrastructures take on a life of their own, and we spend our time reacting, fulfilling functions defined by our constructed habitats.

The Infrastructures Of Global Flow

We have now built, and now maintain infrastructures that operate at massive scales. These are the pipelines, cables, railroads, and freeways by which we move materials and energy from one settlement to another. This system was initially built to support the movement of materials from natural production sites (farms and forests) to industrial production sites in cities (mills and factories). With the advent of colonization, and as we began to deplete the European biosphere, these flows expanded their reach. We “discovered the new world”—a place where people hadn’t destroyed their biosphere. This was the birth of what we call modern civilization. We solved a problem of our own creation, by creating new problems. As we fell deeper into the colonial-industrial system, we developed the illusion that we could live disconnected from the biosphere. We began to live in dead zones, called cities, that survived by draining the life from places that were out of sight.

More and more of our people are involved in tending infrastructures and their effects. Our survival systems have become increasingly dependent on infrastructures with unintended effects that create more work. By determining who in our “complex societies” has more power and ownership, we spend tremendous effort in accounting systems that track the work, rather than evaluating the outcomes of our work or the health of the earth. This whole fragile system is hidden from view by pipes, cables, freeways, shipping lanes, or railroads. We don’t see what is at the end of the pipe.

Global neoliberalism and its accounting system seem to suggest these “pipes” are just laid willy-nilly all over the place, and that everyone benefits equally from the pipework. The more pipes the better. However, this piped flow of global resources is neither equally beneficial nor even benign. Energy and materials flow from extractive production sites to modern settlements. This flow defines a pattern of continuous recolonization–layered histories of natural pattern, good fortune, trauma, control, manipulation, and chance. It is a vast parasitic network. The host is dying.

I suspect that our inability to perceive our social-ecological system and its infrastructures is a deep root of our dysfunction. We are born embedded in this way. We can no longer imagine a simple solution to simple problems. Instead, our attention is fixed on a financial scoreboard, decorated with ideological stories, operating at scales where we have no agency. We are simultaneously entranced, horrified, and riveted upon the colonial-industrial nation-state. We are befuddled as we try to track the pea of our individual security as if in a street-corner shell game. We are simultaneously born to habit, deprived of basic information, rewarded for compliance, and distracted by the cacophony.

We all have roles to play that consume our energy and attention. But very few of us have any cognitive connection to the underlying infrastructures upon which we depend. Those supply lines are taken as given–necessary, practical, essential. By that reckoning we cannot question the importance of sustaining that supply, nor do we follow the pipeline back to its source and seek responsibility for extraction in all its forms. We are born and we play our roles. This modern social-ecological system is both intensely interconnected and in a state of mental torpor, we are ants building a nest we cannot perceive.

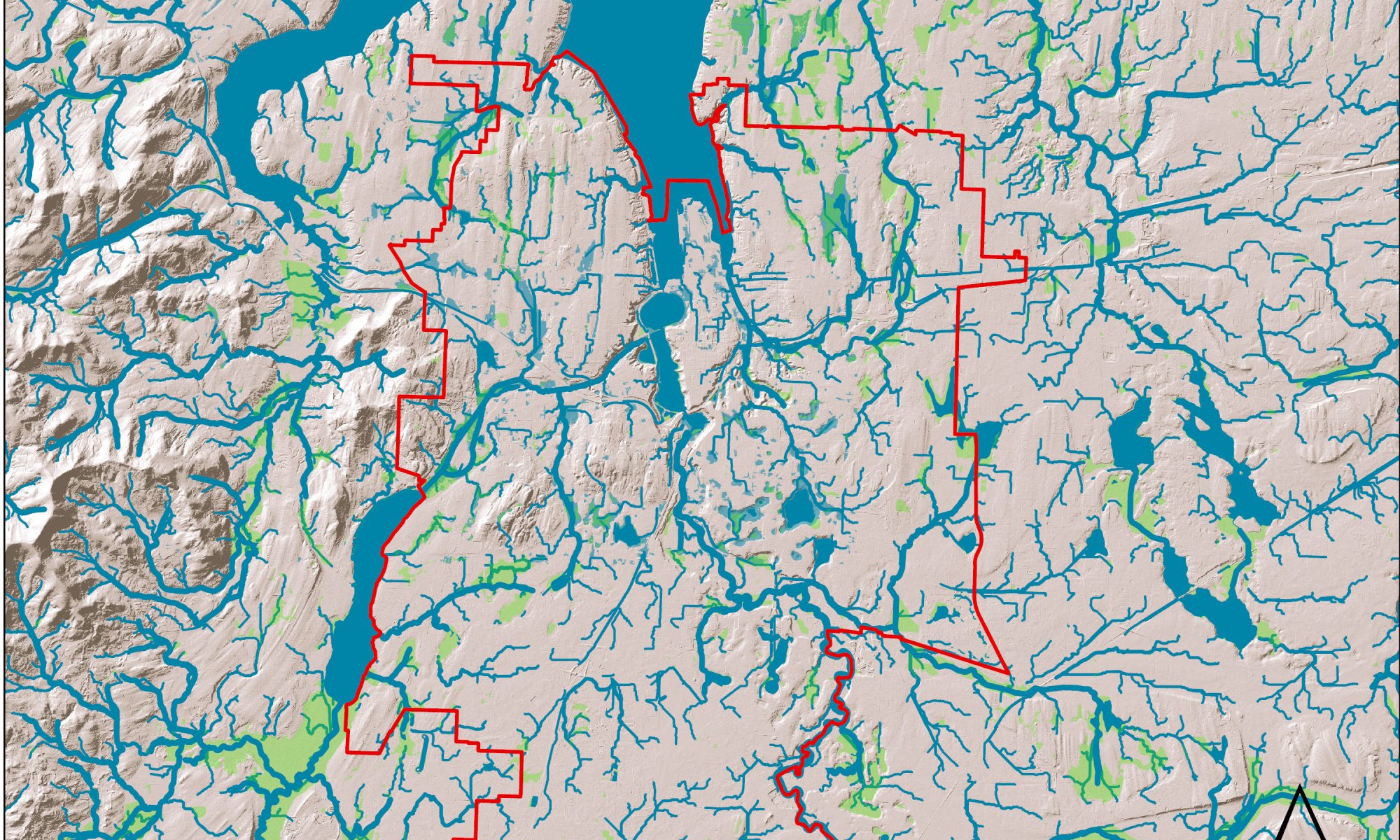

A Regenerative Bioregional Culture For Cascadia

Here in the Salish Sea, we have converted our forests into a fiber factory. Between our national parks and our settled lowlands is a vast foothill landscape that was once a mosaic of ancient forests. It is now enrolled in a global industrial-colonial fiber production system. Before automation and consolidation to maximize profits for investors, our rural settlements used to be bustling production sites. This landscape is now managed to generate a continuous global flow of cellulose and wood. There are many ways to live in a forest, but this particular way provides inexpensive global feedstock for cheap single-use disposable wood and paper economy, from oversized and fragile housing to Amazon shipping boxes. The price is reduced carbon storage, declining biodiversity at multiple scales, fragile hydrology, degraded aquatic ecosystems, and declining quality of fiber.

A regenerative bioregional culture is intimately aware of its infrastructures so that it can evaluate their effects on ecosystem productivity and resilience. A bioregional culture meets its needs by working with the climate, landforms, and biota of a place, and then seeking reciprocal relationships with other bioregions for luxuries. A regenerative culture designs infrastructures that increase the underlying ecological capital of the place we live.

Alternately we can play our role to sustain a system we barely understand, ignorant of the violence and cruelty that sustains our supply lines of feedstocks, petulant if deprived of our inherited privileges, envious if we are born with less, unaware of the fragile nature of our infrastructures. This ignorant, petulant, envious, and unaware state is non-partisan–it is a kind of childhood. You can find threads of this narrative in both liberal and conservative factions of our nation-state. In some ways, fascist and white supremacist narratives may be more conscious of this survival challenge, even as they explore solutions that are unacceptable in their cruelty and inhumanity.

The only way to awaken from this state of hypnosis and delusion is to take stock of our infrastructures. It helps us remember the problems we are trying to solve. That’s why I so appreciate woodcraft, gardening, and backpacking. When you walk away from a road, you are walking away from the colonial-industrial system. What will you bring with you? What burden are you willing to carry, and what will you leave behind? What will you bring for a weekend, or a month, or a year, or to sustain future generations? I can look in a camping kit, and see the seeds of the infrastructures we actually need.

Back in 1995 a landscape mentor told me this and it stuck. After doing a job, we would use a blower and clean out the entrance and paths of a garden job, even if we never touched those areas. Walking outside, the client would see everything looking freshly swept and feel good before they even looked at our work. I remember one job I did for a client–we traded landscaping for voice lessons. She was unhappy with her yard and wanted it more “tidy.” I cut an edge between her shrubs and lawn, and raked all the leaves to cover the newly defined beds. She was gleeful.

Back in 1995 a landscape mentor told me this and it stuck. After doing a job, we would use a blower and clean out the entrance and paths of a garden job, even if we never touched those areas. Walking outside, the client would see everything looking freshly swept and feel good before they even looked at our work. I remember one job I did for a client–we traded landscaping for voice lessons. She was unhappy with her yard and wanted it more “tidy.” I cut an edge between her shrubs and lawn, and raked all the leaves to cover the newly defined beds. She was gleeful.

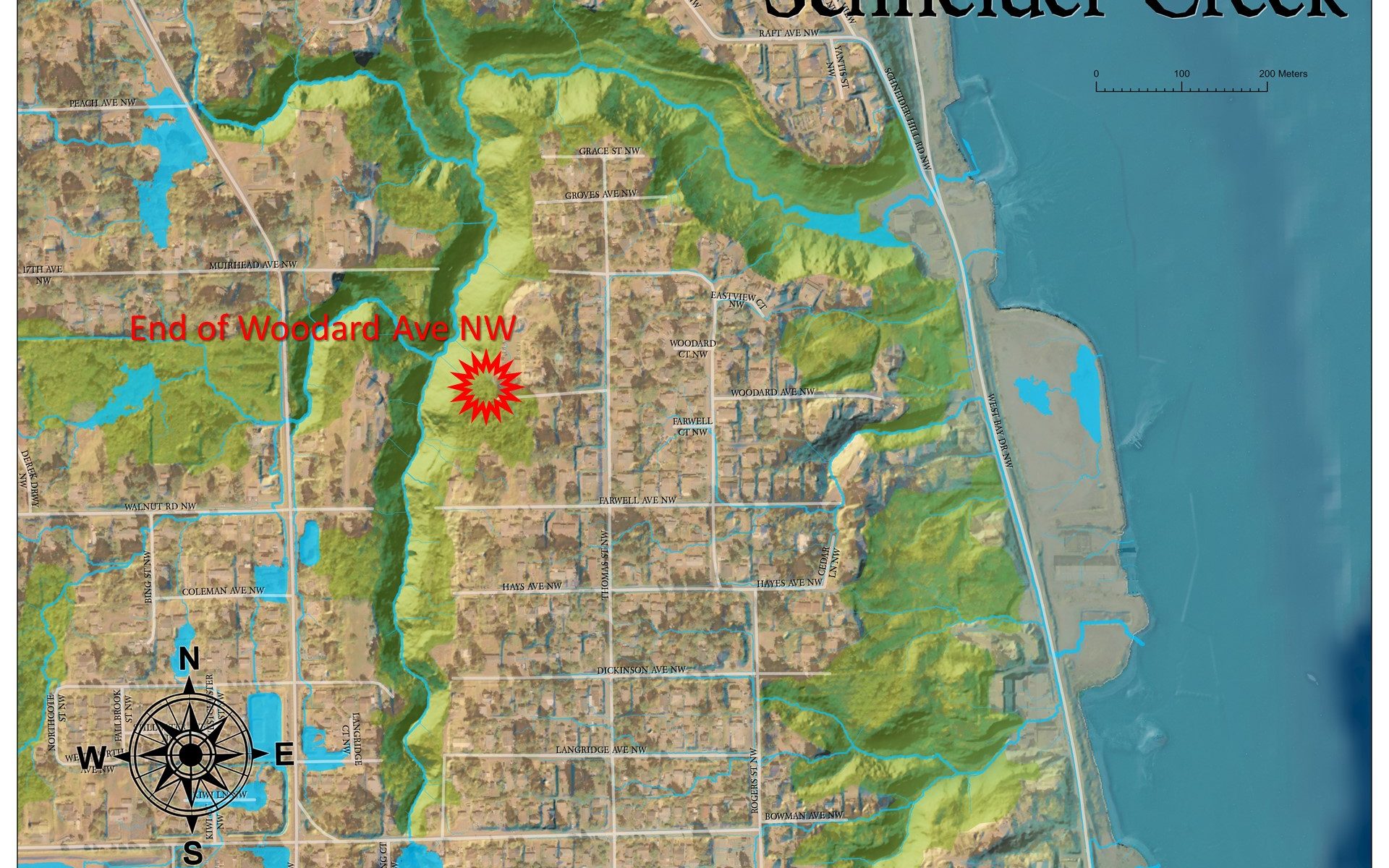

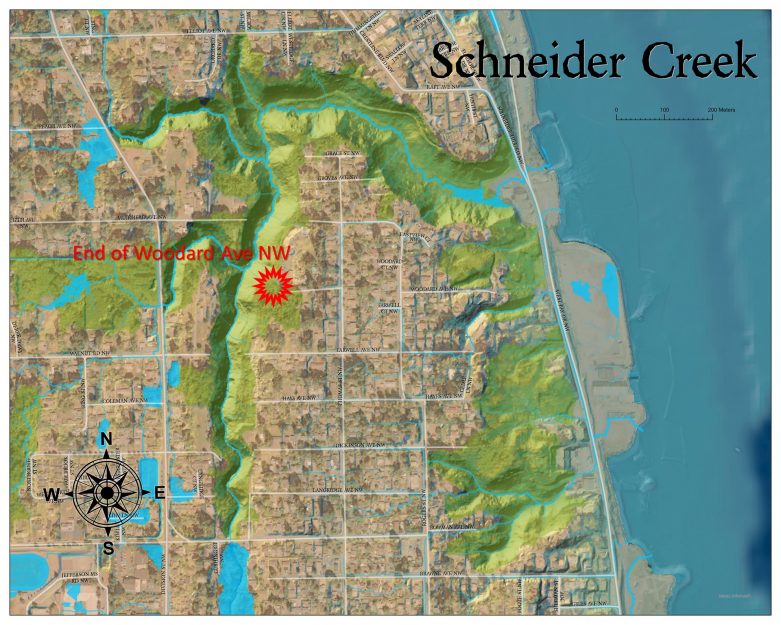

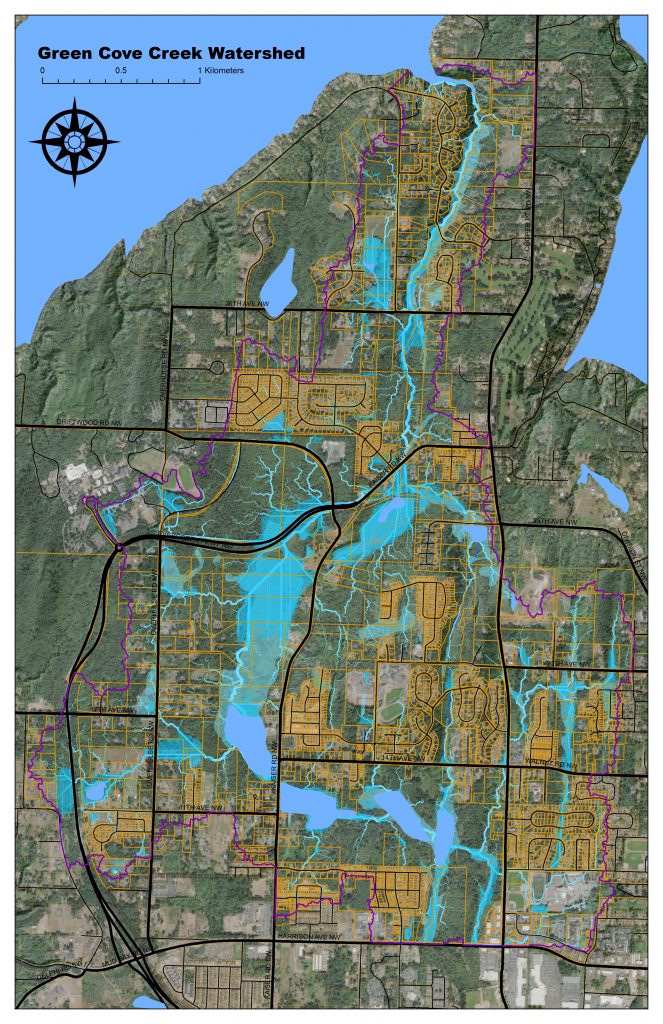

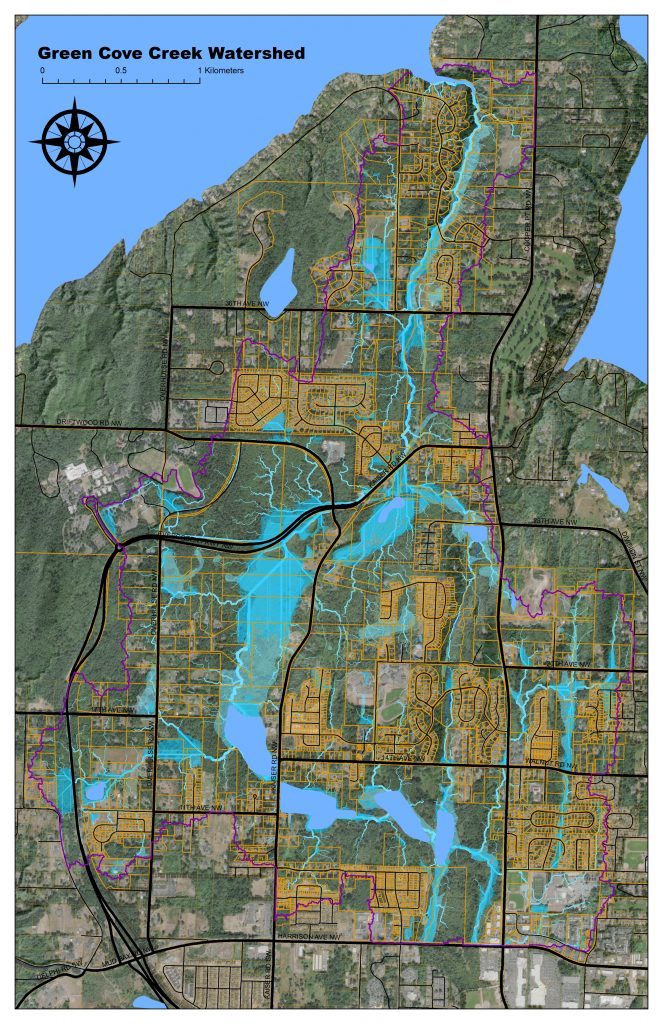

Green Cove Watershed is the largest watershed on Cooper Point on the Edge of the City of Olympia, and the natal site of the Ecosystem Guild. It cradles a vast wetland complex, with amphibians, bittern, green heron, mud minnow and other uncommon species. These wetlands recharge the local aquifer, providing drinking water for the city and residents, and feed a small stream that flows to Eld Inlet, and supports a robust chum salmon run. This tapestry of life has flourished for perhaps 5,000 years under the stewardship of people now known as the Squaxin Island Tribe.

Green Cove Watershed is the largest watershed on Cooper Point on the Edge of the City of Olympia, and the natal site of the Ecosystem Guild. It cradles a vast wetland complex, with amphibians, bittern, green heron, mud minnow and other uncommon species. These wetlands recharge the local aquifer, providing drinking water for the city and residents, and feed a small stream that flows to Eld Inlet, and supports a robust chum salmon run. This tapestry of life has flourished for perhaps 5,000 years under the stewardship of people now known as the Squaxin Island Tribe.