Took too long to get this update out the door.

Writing about my efforts and what I am learning is helping me a little with sense making. It’s also a little bit like a soap opera or una telenovela. You can drop in and follow your favorite plot line, or if you like, binge watch from the beginning. For me it seems a bit like being a circus sideshow plate spinner.

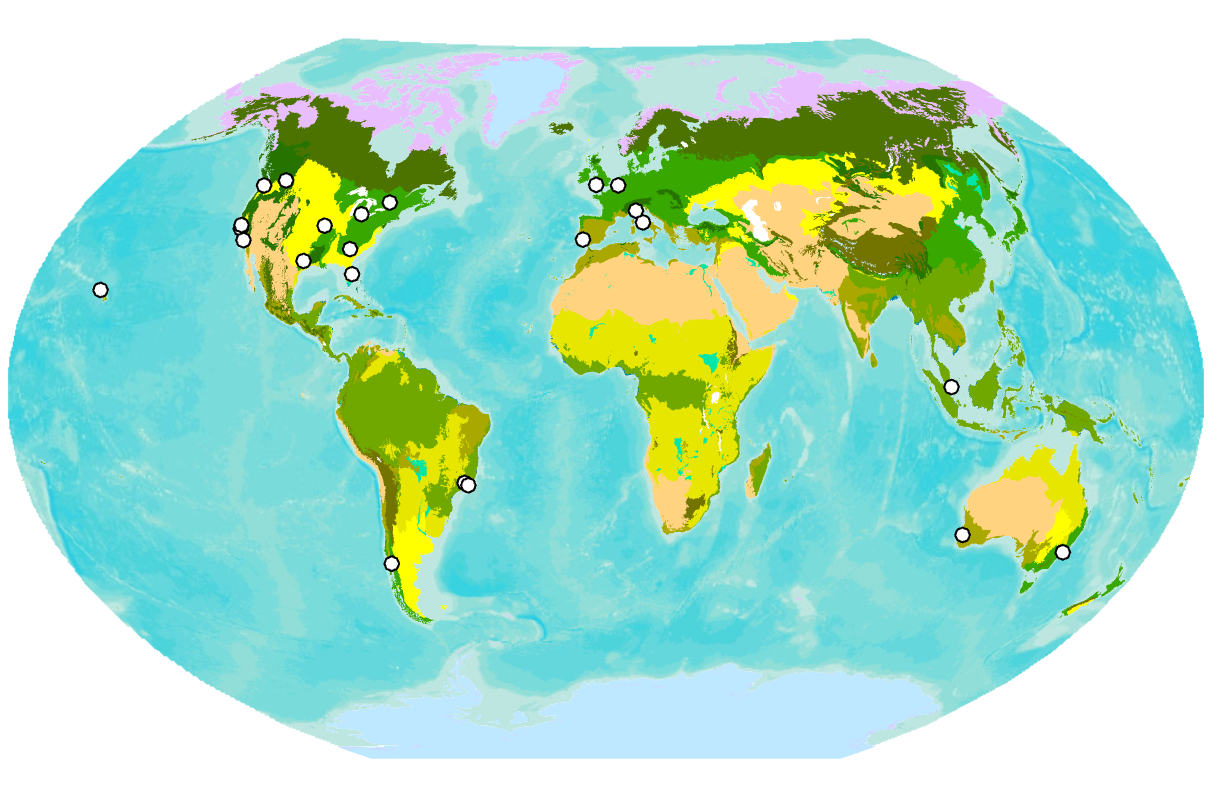

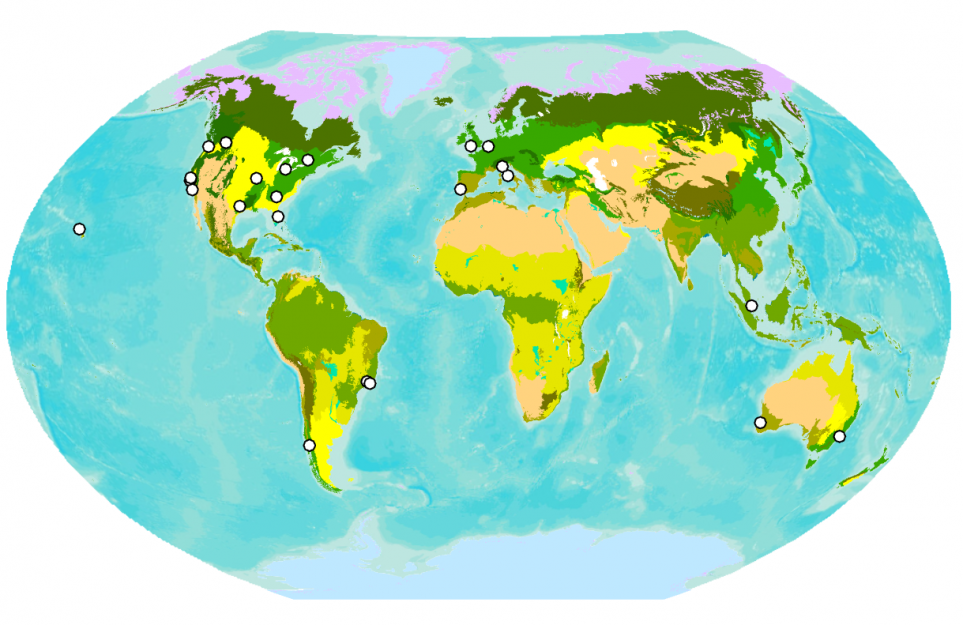

I’ve spent significant effort lately supporting to the extent I can the development of Joe Brewer’s Ecosystem Regenerators Platform. Joe frames a bold vision for a global network of bioregional education centers focused on regenerative culture, and his views on global ecological collapse and the cultural origins of our predicament resonate with me (check out his manuscript). That time interacting with folks from around the English-speaking globe has helped clarify my 30 years of work in the Salish Sea within a global context. We have so much to offer, and so much to learn. The potential to compare notes and strategies with colleagues in other temperate maritime ecosystems is exciting. This digital sojourn has also clarified for me the critical importance of social technology and the unresolved challenge of “group formation”: the art of the yarn, nonviolent communication, prosocial design, and sociocracy (more on all that later.)

I have spent a lot of effort collecting and reading various sources of information, focused on cultural evolution necessary for regenerative bioregional design. That collection of materials is here.

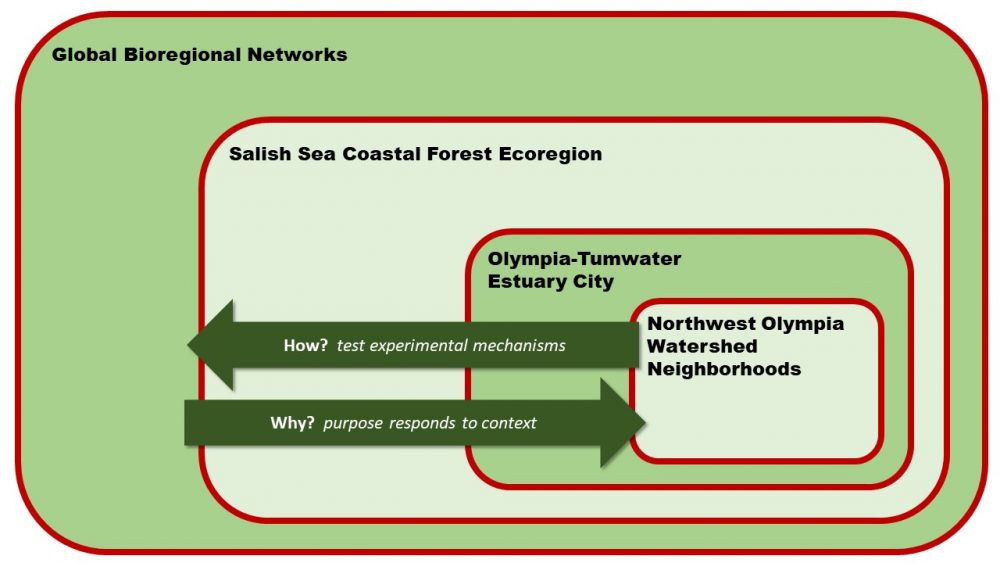

Following that vein, this update tries on a new structure, divided into sections, each section revolving around a spinning plate. My sections follow efforts organized in nested scales from global to neighborhood. I suspect that creating this kind of coherence, so that our local actions make sense in the context of an evolving global ecological collapse will help us see more clearly.

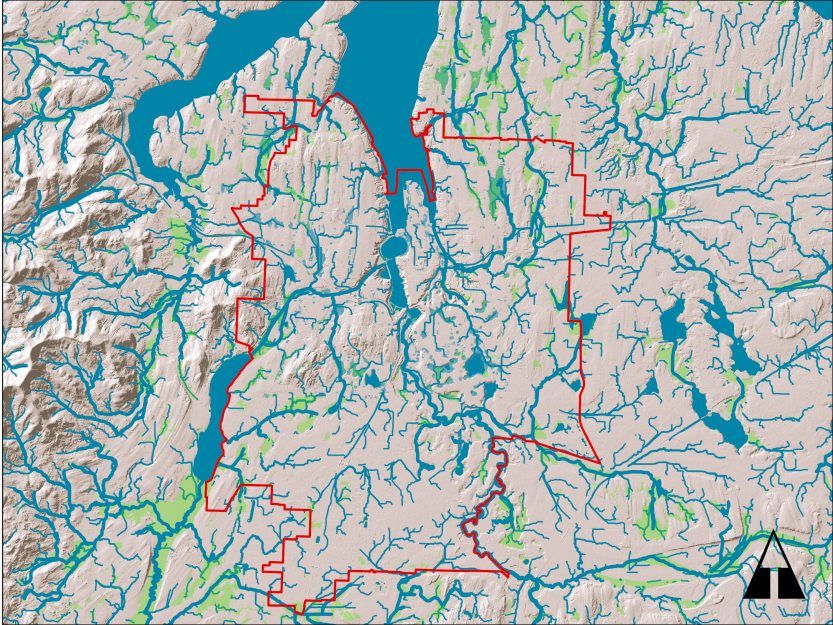

My day job has me focused on the impacts of industrial colonial culture at the scale of our coastal forest ecoregion. Also at this scale, the Salish Sea Restoration Wiki is a tool that straddles public service and private education. We have an undiscovered role within a global bioregional networks. My home is within the NW Olympia watersheds, centered on my cohousing neighborhood where I work with my hands. That work is a local experiment within Olympia-Tumwater, our local estuary city state at the southernmost reach of the Salish Sea. The Ecosystem Guild, and its ability to go restoration camping connects the two scales, linking my neighborhood in my estuary city to other such places within our bioregion. In general I am envisioning a menagerie larger than I can effectively manage, so part of this update is to share this evolving pattern, hoping that someone will jump in if a wobbly plate strikes your fancy.

The Imperial Ecologist

My day job as a federal restoration ecologist is a source of insight, information, capability, and networking, without which I couldn’t do what I am doing. It offers both stability from which to plan and a platform to operate from. I am both grateful for the work, suspicious of its ultimate efficacy, and curious about shaping the governmental platform so that if functions better. In industrial societies like mine, for better or worse, local, state and federal governments capture and distribute a large portion of that collective energy of our civilization that is not focused on private accumulation and instead focused on the public trust. We have left the commons to our bureaucracies. But thankfully at least there remains a significant commons, both in the public landbase and among public trust resources. There are some that would destroy our governments, proclaiming them corrupted and distribute our remaining commons among private interest groups as private properties. Not an improvement of a fragile affair.

One interesting recent event: some colleagues at the Skagit Watershed Council convened a days-worth of presentations on revegetation leaving me with a pile of notes. 180 people from across the Salish Sea showed up, excited to talk and learn. The first half was on climate change and assisted plant migration. The second half was about lessons learned in wetland mitigation. The comments and discussion pointed towards a set of topics that folks are wrestling with. One of these questions was about how the economic and political structures of our restoration industry (driven by state and federal grants) has come to affect how we think about and do restoration (as a capital construction project completed by transient professionals). This is an issue of pivotal importance for the work of our Guild. Contrast this with the emerging vision of biocultural restoration.

Tangentially related, I recently facilitated a workshop on capital programs and climate change using the Three Horizons Framework, and made a video of the introductory presentation. The practice itself is a tool for how complex systems inevitably change, and how we can thinking about human agency within that process of change.

The Salish Sea Restoration Wiki

More than ever, sustaining and building out the Wiki seems to be a multi-scale resource. It contains information about both social and ecological systems. I helped create the wiki back in 2011, and this plate is starting to wobble dangerously. The wiki is parked on an Amazon server, with a volunteer keeping the software alive. I’m running a MediaWiki installation with circa 2011 plugins, and would like to upgrade the user interface. I have an agency sponsor with perhaps $2,500 a year who is willing to keep it alive, but needs a vision and a plan. A public entity, however, won’t host it because of the legal fears and logistical challenges of distributing documents. I’ve had three dead ends even among university and college centers. I am looking for a network solution to solve the need for hosting, stewardship, contract maintenance and improvement, and ultimately to engineer a MediaWiki/GIS interface. I am thinking this might be a place where I need to come up with a chunk of grant under a coalition to stabilize this plate and get it spinning again. I need a motivated and professional technical partner for this work.

The Ecosystem Guild and Restoration Camping

I met someone new through facebook, who is also growing a portfolio of possibility, but from a different and parallel universe. He has worked for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and been deployed to natural disaster sites (floods, hurricanes, etc…) with a focus on logistics technology. He is also on the board of Burners Without Borders which is a spinoff of Burning Man that uses their desert-earned proficiency in self-contained mobile cities to support disaster victims. This new relationship is deeply involved in the technologies necessary to sustain communications systems under collapse, and is similarly interested in ecological sensor arrays that allow us to observe ecological systems at a watershed scale. For example, Raspberry Pi produces cheap cellular ready computer boards that can be used for a wide range of purposes. We wandered the intersection of community development, disaster resilience, rights of passage for youth, mobile restoration camping, online community, collaborative proposals, and project bootstrapping.

I think a video and primer on The Cynefin Framework might be a useful tool for the guild.

This multi-scale inter-disciplinary weaving is fun, but we agreed that it depends on integrated action, and integrated action (that aims to go deep rather than wide) depends on places. We shared our places of interest and arrived at Lopez Island, the Mainstem Skagit River, Lower Skykomish River, as places where we might overlap most easily.

I had a long conversation with a dear friends on Lopez Island, and they are committed to having their 40 acre wetland-forest-farm as a cornerstone of a Lopez Island guild. This would be the easiest to pull off, because it works outside the logistical friction of working in land management bureaucracy, and I have a love of islands and islanders. Lopez is in the rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains, with 27” (680mm) of rainfal in winter, compared to our 50” (1270mm) in my Southernmost Salish Sea. That water provides all their well water, groundwater, irrigation water, fish water, pond water, everything. Our host at Midnights Farm is also a heavy equipment operator, and they run an island wide yard debris composting business that is the foundation of their no till vegetable production. They take WWOOFers and interns, and they are part of broader efforts to bring “rights of nature” into the county charter.

I am contemplating setting aside other site development, and instead focusing on a summer camp on Lopez as a pilot site, for strengthening the bioregional vision of the island and developing an action plan that could be enhanced by seasonal restoration camps, anchoring at Midnight’s Farm. This intention swirls around the sharp unpredictable edges of our evolving global pandemic.

A pandemic also seems to be a time where digital community development may be ripe. Like cold stratification or some other kind of gestation, there may be work to be done that is building structures that can unfold with the spring.

Olympia-Tumwater Estuary City – Local Government Reform

Twice now I’ve met with a new proto-circle and had a long sprawling conversation. Five of us attended, a fascinating blend. I was the only male, which is a subtle shift in dynamics. There was the volunteer for environmental policy at Black Lakes Audubon Society, which is deeply involved in local advocacy. There was a woman who narrowly lost a Port District commissioner position, a historian by training, deeply interested in the bioregional challenge, the third was a friend who is a tireless and aggressive gadfly in the face of local developers and their high-paid teams, working with a self-taught lawyer recluse, and a fourth another ex-bureaucrat distributing copies of essays on The Pluralist Commonwealth.

The short version: fighting development is exhausting, corruption is filling the void in our culture, the culture of environmentalism has been consumed by endless conflict with a tight group power brokers, we need to know what we are trying to create, the laws already exist that state the intention of stewardship, local governments are the arena in which to create bioregional vision and realize the intent of the law. We will meet in late March and revisit our findings.

Most citizens don’t understand how local government works. Its nuances have largely been created by a very small number of individuals that are in the business of catalyzing large development projects to make profit. Based on my limited interactions, these individuals see themselves as a kind of caretaker of progress in colonial society, and see their wealth and power as a sign of their righteousness.

At my day job, I am part of a network of scientists, understand how local government systems work, and who are despondent because the fate of our local ecosystems are in the hands of these powerbrokers. But there are no relationships. The activists, scientists, agency bureaucrats, elected officials, developers, and their gun-for-hire consultants (who are often ex-bureaucrats!) are operating in separate enclaves. Meanwhile the citizens of the place feel left out of the whole process, and tend to mistrust everyone who looks and acts like a powerbroker in variable measure.

I think the first step is in clarifying the nature and rhythm of the system by which the fate of the watershed is determined, under the “policing powers” of the local jurisdiction. Once the dance is clear, then we can place each faction clearly in the dance, and we can select where, when and how we intervene to change the dance. Just kicking a dancer, doesn’t change the dance, and just exacerbates the mistrust build from isolation.

The dance floor for this experiment is the City of Olympia (our organism of interest) and perhaps by extension the City of Tumwater, which together manage the historical landscape that is the Deschutes River Estuary. However it’s the same dance all over Puget Sound, because the dance is governed by state law. This is another prototype situation. I am seeking colleagues working on other dance floors to increase transfer of knowledge (next scale larger). In addition I am breaking down the details of the dance (which revolves around Shoreline Management Act, Growth Management Act, and Capital Plans (such as drainage and stormwater) which creates enforceable codes like the Zoning, building codes, impact fees, shoreline master program, and critical areas ordinance. There is shockingly little ‘complex systems analysis’ at this level (one scale smaller than the organism of interest). What happens on the dance floor if you switch the key of the music?

The Marshall Nursery Guild (Green Cove Creek Watershed)

Two guildmembers from the Marshall Nursery have started up planning to start up nursery work again in anticipation of the fall of 2021. (To be clear, I generally refer to anyone who is voluntarily taking responsibility for bioregional design and stewardship as a guild member!)

The school nursery system is simple. At the beginning of the year we show up with pots, compost, seeds and sources of cuttings and divisions. We tell stories about the location of the school grounds in the watershed, the degraded ecosystems, the idea of a commons, and the value of building a commons within the school and watershed. We teach labor (yes, knowing how to labor effectively is a skill that most industrial youth don’t have and you have to teach them how to labor or most of them are almost useless and feckless–this is a class and subculture phenomena that is interesting and important). We then organize our collective labor to potting and planting all winter using various self-organizing strategies. By May we have potted stock to sell to families, and the rest is held over summer in beds. In fall we sell more stock, install restoration projects, and start over again.

The nursery project was my first attempt at facilitating formation of an autonomous volunteer team. At the end of the day, the project seems to be mostly about individual relationships. The team doesn’t meet regularly and communications only as much as necessary. It seems to be revolving around the teacher and the nursery. This is unfortunate, since the teacher may be the one person least able to coordinate, not having a surplus of horticultural skills and with their plate full of being a middle school teacher. If there were volunteer network able to recruit and sustain group processes, that would serve the teachers better, and be able to scale up. I have in the past tried to facilitate more group process, but that is not the natural pattern. I am left contemplative, and content to let it evolve rather than trying to interfere.

I believe my personal interests in this effort are around replicable system development: I would like to define the minimum technical and social scaffolding necessary to allow any middle to high-school with willing volunteers to initiate plant production as part of science and CTE programming. I’d like this work to connect the school as a facilitator of local restoration efforts, and lead to the regeneration of the school grounds. Schools are an under-capacitated commons infrastructure in the center of every community. Families care about their children. Children are better able to love the earth. But we need to avoid colonizing schools and making schools carry more burden for a broken society, but rather bringing our community in to gather around schools with a broader and expanded vision of what a school is in a community.

If we can figure out group formation in support of the school, and can develop more group functions, then network among groups could make each school stronger. I would love to cultivate a community that can curate and build out School Nursery Resources, as part of building the replicable social infrastructure. That plate will need to be spinning by fall of 2021, however new viral variants make the future of public education complex. I wonder how to engage an Evergreen Student working on bioregional education for an industrial middle school, in a way that supports coherence of the support group, perhaps as part of teaching social technology? I think my pathway here is still in training. I have started playing around with unstructured video resources at my home nursery:

And here’s a more involved exploration of Fireweed:

WoodLaCoHo and St’uchub Ravine Neighborhood

The most significant change since my last update, has been moving into Woodard Lane Cohousing in the NW Neighborhood of Olympia.

Life at “the commune” is a lovely anchor. I put out a call for a garden flash mob and got three people who helped me pull out infrastructure so I could rehabilitate a large section of our garden. I am so grateful to live in the constant presence of a helping hand. The garden infrastructure on the other hand is a classic example of a systems failure triggered by one narrow decision that then drove a cascade of decisions. This is what Mollison would have called a type #1 error–an initial design mistake after which you spend the rest of your life working to maintain. I made a quick video describing the failed system, and some of the standard drip irrigation solutions I have come up with over time, based on many mentors.

It is both a pleasure and a burden to come into a community where I am one of a handful of individuals with a love of laboring and with construction experience. The community formed around a vision of interpersonal relationships, and some deep skills around sociocracy, mediation and nonviolent communication. They don’t necessarily dedicate a commensurate effort with buildings or drainage systems or the forest edge. They do a great job supporting each other and having regular meals together, and pulling together for work parties, and it’s a good place to try to survive a global pandemic.

Some significant garden improvements are underway, I have established a small native plant nursery, and the tool shed and wood shop are now organized and cleaned out. I set up a potting bench under shelter, and blackberry cleared our sections of our 60 acre Schneider Ravine forest, ivy pulled off trees, and deer trails explored. There is always work to be done.

This tension between the physical and ecological dimensions of a community and the social dimensions of a community is an interesting play on Ostrom’s rules. The commons are both physical and social, and there is work to do in both. However, if in a community, many are busy with social contributions, while the physical work falls on a few people this is a potential source of strife. Stewardship capability promises to be a long topic. On the other hand our little community of 18 households has a lot to offer our neighborhood and surrounding community.