This is one of a series of essays inspired by a study group hosted by Joe Brewer and Diego Galli on cultivating a culture capable of regenerating the earth. I am grateful for the opportunity to reconsider my work through this lens.

A note on the use of “restoration” and “regeneration” and “stewardship”: I use these terms interchangeably to describe cobbling together ecosystem functions lost during colonization or more generally, civilization. This blurry view might bother people invested in a particular philosophy. I suggest we go somewhere and focus on the work.

Enabling Conditions for Restoration

Before I was a restoration ecologist in the Puget Sound I was a laborer. I am grateful for my shovel work because it helps me differentiate between the actual labor of restoring ecosystems, and the efforts to creating the circumstances that enable the work to occur. Good restoration labor is enabled by the coincidence of circumstances–the right resources, knowledge and labor arrive the right place at the right time. That enabling effort is necessary, but is not the work of restoration itself. Right now we struggle to create enabling conditions around each new project. This is because we are attempting restoring outside of a culture of restoration. We not only must do the labor, but we must laboriously build the foundation upon which the laborer must stand. Under these conditions, we spend too many resources to accomplish too little as our damaged earth continues to unravel. However if we can lay a broad enough foundation the regeneration of the earth will be relatively simple.

What is this cultural foundation? We will not know “regenerative culture” by the books we read, the music we listen to, or what we post on social media. When we are ready to regenerate the earth, we will take our tools and our short lives, and we will serve plants, deepen soils, and recharge groundwater. We will tend to the fate of each species with our hands. We best know a culture not by its intentions, but by what it does. While this may be obvious, it seems useful to repeat the obvious. Our virtual lives, on this screen in front of you, or in our heads, will not restore ecosystems. Tending the earth happens when we are hands-on and unplugged.

The Japanese have a word “gemba” which describes the place where the action happens. Reporters report from gemba. Japanese and American industrialists adopted the term to describe the factory floor, where the things we value are actually created. The term is now used ritually across modern manufacturing to refocus management attention to where the value is actually created–the place where laborers make things we want (see Imai 2012). From this perspective, management is waste, and a good system works well with less management. When contemplating ecosystem restoration, and the conditions that support it, we may be served by keeping our mind on gemba.

We can have many conversations about regenerative philosophical frameworks. But if you want to see a culture of restoration, go to gemba. Go to the place where people meet the land and observe what they do. Once there, you will find people struggling to do the labor of restoration. If you ask good questions and listen carefully you can understand what they need. You can start to imagine the tangible form of a culture of stewardship, because that culture would support the work. In turn, if we are wise, our attention to the labor itself will shape our culture.

Design From Where We Are

In my home on the South Salish Sea, if you go to gemba , regenerative work is done by people working for Indian nations, county conservation districts, local public works departments, a handful of non-governmental organizations, and a few adventurous farmers. This work is mostly impelled by taxes that are distributed through state and federal grants. The grants flow into contracts to hire engineers, excavators, foresters, landscape contractors, or conservation corps. There are a few private landowners doing the work, often at a limited scale and in relative isolation.

As a bottom-tier bureaucrat, I now sit in the middle of this system, in front of a computer leveraging legal authorities, financial accounts, paychecks, contracts and stories. I don’t do a lick of labor. My partners work as project managers and in turn hire construction crews to take out dams, put bridges over streams, pull rock out of rivers, dig holes and channels, fence cows, and pay landowners to pull back from streams and plant trees. I am not saying that this is the right way or the only way to do the work, but right now, this is our community of practice—perhaps a couple thousand people in a couple hundred institutions over 13,000 square miles.

Despite the importance of restoration on a damaged earth, the nature of my industry is nearly invisible to the public eye. Our activities only touch a few places at any time. We do small capital projects, within in broader culture that has a limited conception of ecosystems and stewardship. We don’t tell good stories. When I describe my job, people politely act like they understand, but I know they don’t.

Our cash flow is a trickle siphoned off a vast industrial economy. In Washington State over seven million people drive 61 billion miles per year. Twenty million tons of goods flow in and out of ports, and we consume 2 quadrillion British Thermal Units of energy to generate $350 trillion in economic activity in a landscape of pavement, pipes, cables, bridges, and buildings.

By contrast, our ecosystem restoration work is less than one tenth of one percent of this industrial frenzy, and our political benefactors, reading the tea leaves of power, fund this level of work, because that is all their patrons will tolerate. After all the paperwork and planning to create enabling conditions, only a small portion of revenue gets to gemba, to change the ecosystem. This is restoration, without a culture of restoration. If our global state credit rating falters, the restoration industry would convulse. At this moment, however clumsy, it is still a beautiful thing, and it’s what we’ve got. It is a situation worthy of study, and rich with opportunity and stories.

The Case Study of Restoring Estuaries

Because we are on the emerald edge of North America we care about Pacific salmon, a 10,000-year-old oceanic blessing on our lands and waters. Because these fish depend on estuaries, one of our earliest efforts has been to restore the marshes and swamps at the mouths of rivers. These are the places where young salmon transform from freshwater to saltwater creatures, and fatten up to survive the ocean. If there is too little estuary, the population is weak. We strengthen spawning and rearing in the rivers where we live, to enable ocean survival, where we have less control.

The easiest way to restore an estuary is to reconnect the rivers to their floodplains and get all our roads and buildings and ditches out of the way. Once unconstrained, the rivers and tides and plants do the rest. This mostly requires enough money to hire excavators and dump trucks for a summer’s-worth of work and getting the many concerned parties to come to agreement. In the case of the Nisqually River Estuary, this required around $22 million over 5 years to initiate restoration of around 1,000 acres–almost nothing compared to one of our road building projects. However unlike road building, our social infrastructure doesn’t support the work. The project teams had to create the enabling conditions.

In this way, over the last 15 years, the Nisqually, Skokomish, and Little Quilcene deltas have begun to regenerate, at a cost of around fifty thousand US dollars per acre. There are still a few complexities–for example a regional superhighway still cuts across the Nisqually floodplain (as seen above) constraining the flow of water and sediment. However, with rivers and tides free to work, these wild systems will sustain themselves forever. There is still much work to be done. Some smaller estuaries have been obliterated, and restoration would require excavation of vast quantities of soil, sluiced off of hillsides. Other estuaries are laced with roads, drainage ditches, family farms, fire stations, wedding venues, airport flight paths, toxic waste and neighborhoods. By a wicked coincidence, a significant land base for our future food security (including for 50% of the global beet seed supply) is below sea level, in low-lying river deltas on the Salish Sea. The ground is sinking, and the sea is rising.

So this is real work and progress. It is also the tip of an iceberg, and if we plan it right, the point of a spear. How do we get from a small but passionate sidecar industry that most citizens have never heard of, to a culture of stewardship and regeneration that guides our daily lives. I would propose that we must start with what we are doing, and leverage that into something incomprehensibly larger. I think we can best learn by studying gemba.

In 2015 I had a chance to drive around Puget Sound and ask local restoration teams what it takes to restore an estuary. I met with around sixty project managers and coordinators in nine watersheds, ending with a report (Cereghino 2015). I went to gemba and asked questions. While the title was “recommendations to accelerate estuary restoration in Puget Sound”, in those meetings we were talking about something larger. What are the enabling conditions that allow us to restore ecosystems? Each group considered and refined the thoughts of the previous group. They all had similar ideas about the practical barriers they faced across rural and urban project sites. They identified six conditions.

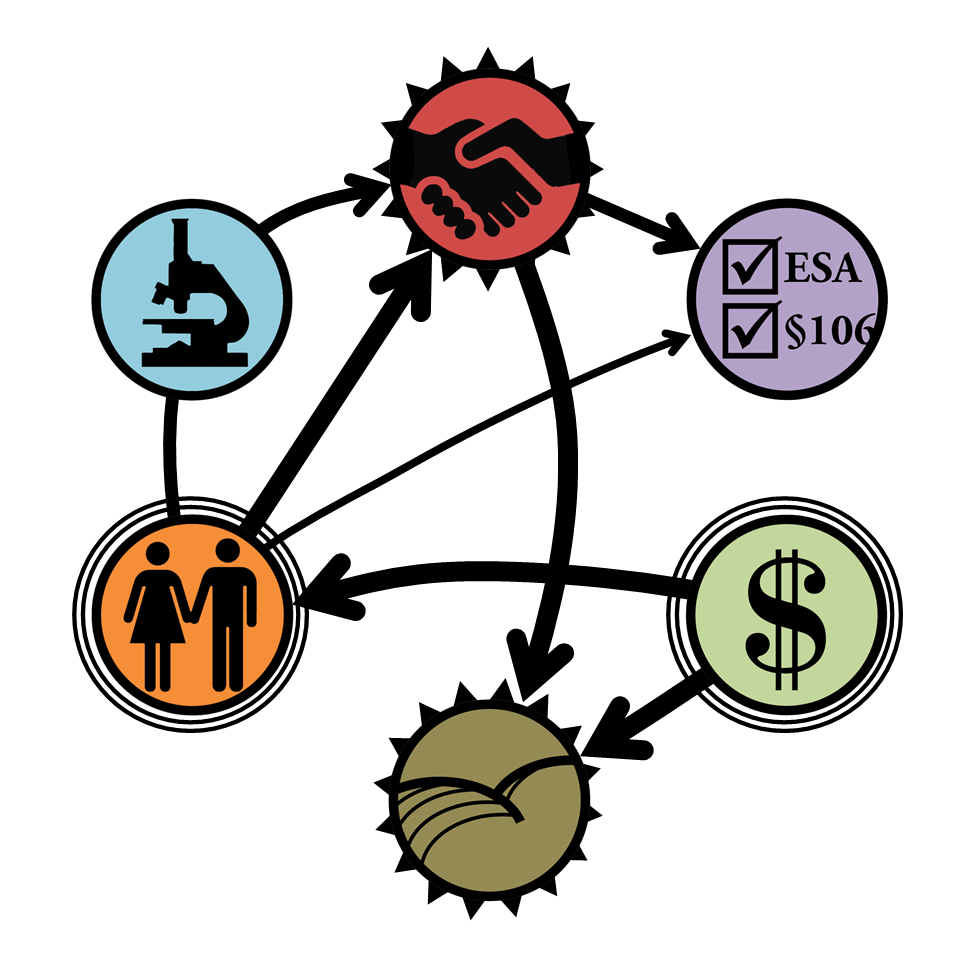

Six Conditions

I am not saying these six conditions are the ingredients of a regenerative culture. I suspect we have no idea of our ultimate cultural destination. It may have something to do with how we think about kinship and our responsibility to other species. It may lead us to reconsider some of our more frantic behaviors. Regardless, if we escape our degenerative culture, it will be through doing the work of restoration. We start where we are.

My examples describe large agency efforts I am familiar with, requiring hydraulic models and millions of dollars in construction contracts. But at its heart we just agree to work together to move some dirt. I bring up these large projects, not to impress or intimidate. I believe they are at their heart no different than what a community could do with shovels (or perhaps a neighbor’s backhoe). The enabling conditions are the same.

Around 10 years ago a local colleague described the restoration of Smith Island in the Snohomish Estuary as “faith-based restoration.” When his team launched the effort in earnest they had no idea what it would take, and how they would get it done. Nisqually was both a lifetime of work by the tribe and allies, and a fluke, with financing driven by panicky stimulus funding after the 2008 real estate market collapse. The mechanisms and precedents for doing those projects didn’t exist when they were initiated. They broke trail through doing the work. Ultimately Smith Island required creation of a new state appropriation to support projects like Smith Island–the Puget Sound Acquisition and Restoration Fund for large capital projects. It was the opportunity to restore Smith Island that helped create the ability to restore Smith Island. Here are the six ingredients they needed:

Project Managers – A herd of people does not necessarily do useful work. Someone in the crowd must take the time to envision the future, and to work out the details. They must organize the herd. The critical skills are not ecological, but rather social. Mobilization alone is not enough. Although a related art, rabble-rousing is not project management. A restoration project manager can envision the destination, and work backwards to plot the course. Consistency matters. Good ideas are cheap and plentiful. Events come and go. It may take years or even decades to deliver a complex project. Someone needs to cultivate and nurture large project consistently, to step back and forth between vision and practice, again and again. To have this devotion, most people need some training and tangible support. Usually this comes in the form of a paycheck from an institution and colleagues. Any institution can work, based on any cash flow. You can push-start a project with volunteers, and then an unexpected institution might step up to play a key role. You can create new institutions, or better yet, entrain, empower, or connect existing ones. However, you cannot finish a project without a project manager. It’s the existence of that individual human that counts. It is that individual human that takes responsibility for weaving the threads. The skill sets can be taught, but the motivation and consistency is what matters and may be hard to cultivate. The project manager must pivot and weave with every nuance of context, not be deflected from the goal, speak carefully, and return all phone calls.

Project Managers – A herd of people does not necessarily do useful work. Someone in the crowd must take the time to envision the future, and to work out the details. They must organize the herd. The critical skills are not ecological, but rather social. Mobilization alone is not enough. Although a related art, rabble-rousing is not project management. A restoration project manager can envision the destination, and work backwards to plot the course. Consistency matters. Good ideas are cheap and plentiful. Events come and go. It may take years or even decades to deliver a complex project. Someone needs to cultivate and nurture large project consistently, to step back and forth between vision and practice, again and again. To have this devotion, most people need some training and tangible support. Usually this comes in the form of a paycheck from an institution and colleagues. Any institution can work, based on any cash flow. You can push-start a project with volunteers, and then an unexpected institution might step up to play a key role. You can create new institutions, or better yet, entrain, empower, or connect existing ones. However, you cannot finish a project without a project manager. It’s the existence of that individual human that counts. It is that individual human that takes responsibility for weaving the threads. The skill sets can be taught, but the motivation and consistency is what matters and may be hard to cultivate. The project manager must pivot and weave with every nuance of context, not be deflected from the goal, speak carefully, and return all phone calls.

Land Tenure – Ecological regeneration must do work on land. Under our global land ownership system just about every square inch of earth is allocated to some owner in some nation. The complete enclosure of the globe is perhaps the great feat of the colonial age. In my home landscape this began with vast imperial claims, allocation of huge blocks among railroads and timber barons, the subdivision for homesteaders, the attempted extermination of Indian sovereignty, the manipulation of value though construction of a spider-work of freeways and roads, and now the aggressive swapping and partitioning under a regulated real estate system designed to serve speculation and capital flow. To rebuild the river corridors of Puget Sound will require organizing thousands of land owners, one at a time. The more finely divided the landscape the more complex this challenge. The mechanisms for building this network are diverse. You might buy, lease, subdivide, file an easement, or work under an agreement, a contract, or a handshake. Land access is created through face-to-face relationships, knocking on doors, browsing county parcel maps, and noticing signs. Land owners talk to their neighbors, and the vital ingredients are trust and motive. In my culture, private land is guarded with a mix of pride and insecurity. A landowner needs a chance to examine a tenant or an offer without feeling unsafe. Governments are poorly positioned to do this work, and land trusts and tribes move quietly and carefully to acquire lands, using state and federal grants. This acquisition system is complex and flawed, and there is no shortage of land needing stewardship. A single Washington State grant database reveals over 2,700 acquisition projects valued at over 2.3 billion US$ over the last three decades. What we lack are the mechanisms for cultivating ecological stewardship. In this work our colonial institutions and allies are equipped to acquire, but ill-equipped to tend or build relationships. Modern conservation tends to see our human communities as a destructive rabble to be kept at bay. Institutions like to work with institutions. That part of the problem deserves another essay.

Land Tenure – Ecological regeneration must do work on land. Under our global land ownership system just about every square inch of earth is allocated to some owner in some nation. The complete enclosure of the globe is perhaps the great feat of the colonial age. In my home landscape this began with vast imperial claims, allocation of huge blocks among railroads and timber barons, the subdivision for homesteaders, the attempted extermination of Indian sovereignty, the manipulation of value though construction of a spider-work of freeways and roads, and now the aggressive swapping and partitioning under a regulated real estate system designed to serve speculation and capital flow. To rebuild the river corridors of Puget Sound will require organizing thousands of land owners, one at a time. The more finely divided the landscape the more complex this challenge. The mechanisms for building this network are diverse. You might buy, lease, subdivide, file an easement, or work under an agreement, a contract, or a handshake. Land access is created through face-to-face relationships, knocking on doors, browsing county parcel maps, and noticing signs. Land owners talk to their neighbors, and the vital ingredients are trust and motive. In my culture, private land is guarded with a mix of pride and insecurity. A landowner needs a chance to examine a tenant or an offer without feeling unsafe. Governments are poorly positioned to do this work, and land trusts and tribes move quietly and carefully to acquire lands, using state and federal grants. This acquisition system is complex and flawed, and there is no shortage of land needing stewardship. A single Washington State grant database reveals over 2,700 acquisition projects valued at over 2.3 billion US$ over the last three decades. What we lack are the mechanisms for cultivating ecological stewardship. In this work our colonial institutions and allies are equipped to acquire, but ill-equipped to tend or build relationships. Modern conservation tends to see our human communities as a destructive rabble to be kept at bay. Institutions like to work with institutions. That part of the problem deserves another essay.

Knowledge – Once you have people who can envision the destination and access the land, you can get to work. You need enough understanding of the land and its creatures to know what to do. This isn’t an abstract knowledge or just knowing the names of things. It is not taught in a university (I know, I was there). One ecologist mentor suggested that to understand a living thing, you must not only know the thing itself, but what is happening around it in its landscape, and within its body–its biology. To make sense of a place, you need to step back far enough so that you can see the forces and processes and evolutionary heritage of a place. And you must also understand each working part, and the small human strategies and tools by which we change landscapes, and how they fit into the choreography of a solar year. This is a deeper knowledge of systems, along with the traditions of wildland tending, agriculture and construction. These tools are unpredictable in practice, requiring the use of intuition informed by experience. Regenerating the living skin of the earth is a craft. It is best accomplished as a creative experiment, with unfiltered information flowing between the hand and the mind and the gut. It also helps to have a healthy pile of high resolution topographic measurements. Unlike cash, knowledge is a resource that builds itself over time and grows through collaboration–a positive feedback loop. It has collective dimensions if we have the infrastructure to store, share and retrieve knowledge within a community. You can buy knowledge into a project. However the cloistering of knowledge in universities, professional societies, and proprietary brands, for the profit and aggrandizement of narcissistic institutions and individuals, is likely part of our problem. Fortunately information flows easily.

Knowledge – Once you have people who can envision the destination and access the land, you can get to work. You need enough understanding of the land and its creatures to know what to do. This isn’t an abstract knowledge or just knowing the names of things. It is not taught in a university (I know, I was there). One ecologist mentor suggested that to understand a living thing, you must not only know the thing itself, but what is happening around it in its landscape, and within its body–its biology. To make sense of a place, you need to step back far enough so that you can see the forces and processes and evolutionary heritage of a place. And you must also understand each working part, and the small human strategies and tools by which we change landscapes, and how they fit into the choreography of a solar year. This is a deeper knowledge of systems, along with the traditions of wildland tending, agriculture and construction. These tools are unpredictable in practice, requiring the use of intuition informed by experience. Regenerating the living skin of the earth is a craft. It is best accomplished as a creative experiment, with unfiltered information flowing between the hand and the mind and the gut. It also helps to have a healthy pile of high resolution topographic measurements. Unlike cash, knowledge is a resource that builds itself over time and grows through collaboration–a positive feedback loop. It has collective dimensions if we have the infrastructure to store, share and retrieve knowledge within a community. You can buy knowledge into a project. However the cloistering of knowledge in universities, professional societies, and proprietary brands, for the profit and aggrandizement of narcissistic institutions and individuals, is likely part of our problem. Fortunately information flows easily.

Cash Flow – I think I’ve mentioned cash at least twice so far. There are many ways to reduce project dependency on currency, but perhaps no way to completely avoid the industrial marketplace. Industrial machines and resources produced in mines and factories born of bank capital are paid for with bank currency. The easiest way to sustain project managers and craftspeople in their work is to give them a chunk of currency. There are perhaps four mechanisms available to generate cash flow for restoration: public funding to provide public ecosystem services, private payments for mitigation services, sale of marketable products from restored lands, and payments for recreational or educational use of restored lands. By far, my industry currently operates almost entirely on public funding. To move past where we are, will require an integration of the restoration economy into our broader economy. Until then, cash is used to buy project managers, knowledge, land access, and the reports necessary for government permission. Without cash, everything becomes a do-it-yourself project. Now that I have elevated the importance of cash flow, I would also like to lay it low. We use cash to replace culture. We have everything we need to do this work, but we don’t do it, because we have been devoured by a social system based on bank debt currency that is destroying the surface of the earth. Cash flow solves many problems except the one that is most important to solve. We should sit with that possibility for a while.

Cash Flow – I think I’ve mentioned cash at least twice so far. There are many ways to reduce project dependency on currency, but perhaps no way to completely avoid the industrial marketplace. Industrial machines and resources produced in mines and factories born of bank capital are paid for with bank currency. The easiest way to sustain project managers and craftspeople in their work is to give them a chunk of currency. There are perhaps four mechanisms available to generate cash flow for restoration: public funding to provide public ecosystem services, private payments for mitigation services, sale of marketable products from restored lands, and payments for recreational or educational use of restored lands. By far, my industry currently operates almost entirely on public funding. To move past where we are, will require an integration of the restoration economy into our broader economy. Until then, cash is used to buy project managers, knowledge, land access, and the reports necessary for government permission. Without cash, everything becomes a do-it-yourself project. Now that I have elevated the importance of cash flow, I would also like to lay it low. We use cash to replace culture. We have everything we need to do this work, but we don’t do it, because we have been devoured by a social system based on bank debt currency that is destroying the surface of the earth. Cash flow solves many problems except the one that is most important to solve. We should sit with that possibility for a while.

Local Agreement – The act of restoration or regeneration likely involves doing things differently then they were done before. Change can create new winners and losers. Removing rock from a river, may let the river consume a farm field. Surging beaver populations clog drainage channels and blow out culverts. Sometimes a new system just feels wrong to the sensibilities and traditions of neighbors raised to things the way they were. There are both subtle and direct ways that local animosity can derail a project or undermine the next effort. Local disagreement can result in loss of access to land. It can undermine cash flow, as funders and investors avoid controversy and risk. Local conflict consumes the labor of the project manager, a often limited resource. It is easier to avoid conflict then to resolve conflict once lawyers get involved. Interestingly, it is still difficult to buy local agreement. People have pride. Trust is earned, and built on mutual understanding and respect. We live in what academics call a “polycentric natural resource governance system”. The intersections of power can be difficult to locate. The process of building local agreement is the process of revealing hidden power structures. Looking at this from the other side of the equation, a restoration mentor once told me, “if you are not pissing someone off you are probably not doing anything.” So we must also learn to piss people off with respect and compassion.

Local Agreement – The act of restoration or regeneration likely involves doing things differently then they were done before. Change can create new winners and losers. Removing rock from a river, may let the river consume a farm field. Surging beaver populations clog drainage channels and blow out culverts. Sometimes a new system just feels wrong to the sensibilities and traditions of neighbors raised to things the way they were. There are both subtle and direct ways that local animosity can derail a project or undermine the next effort. Local disagreement can result in loss of access to land. It can undermine cash flow, as funders and investors avoid controversy and risk. Local conflict consumes the labor of the project manager, a often limited resource. It is easier to avoid conflict then to resolve conflict once lawyers get involved. Interestingly, it is still difficult to buy local agreement. People have pride. Trust is earned, and built on mutual understanding and respect. We live in what academics call a “polycentric natural resource governance system”. The intersections of power can be difficult to locate. The process of building local agreement is the process of revealing hidden power structures. Looking at this from the other side of the equation, a restoration mentor once told me, “if you are not pissing someone off you are probably not doing anything.” So we must also learn to piss people off with respect and compassion.

Government Approval – At some point in time, if you aspire to do something at a meaningful scale, you will run into the apparatus of the bureaucratic nation state. In the Salish Sea, I live in the City of Olympia, incorporated in Thurston County, in Washington State of the United States of America. If I want to modify an estuary, I will need permission from no less than eight local, state and federal agencies and probably two Indian nations. This permission is obtained through the prolonged ritual exchange of documents. Each of these hierarchies is concerned about different things, speaks a different language, and they may contradict each other. Their staff are overworked and are suspicious from being lied to constantly. A complete regulatory process on a large complex project may easily take more than a year. Not one of these institutions has the capacity to improve the system they are locked into, and there is little capacity or incentive for collaborative improvement. An agency may face legal suits if it is either too lenient or if it is too restrictive. You will never understand an institution by looking at their website. To learn how an institution thinks and works you need to talk to insiders. Show them care–its not easy in there. Fortunately citizens can do a great deal of restoration without getting involved in this shit-show, and you might even use it to your advantage. Governments are afraid of community discord, but are equally hungry for community solidarity. Leaders will race to get to the front of a parade that reflects consensus and clear direction. As with land access, government agents often lack the social networks and freedom to do the work of building community vision. Arranging for government approval may seem like a barrier, it may also become a tremendous resource. I would propose that in many situations the inability of governments to support regeneration is more of a symptom then a cause. Our governments are lost in the incoherence and tumult of our colonial culture, just like we are.

Government Approval – At some point in time, if you aspire to do something at a meaningful scale, you will run into the apparatus of the bureaucratic nation state. In the Salish Sea, I live in the City of Olympia, incorporated in Thurston County, in Washington State of the United States of America. If I want to modify an estuary, I will need permission from no less than eight local, state and federal agencies and probably two Indian nations. This permission is obtained through the prolonged ritual exchange of documents. Each of these hierarchies is concerned about different things, speaks a different language, and they may contradict each other. Their staff are overworked and are suspicious from being lied to constantly. A complete regulatory process on a large complex project may easily take more than a year. Not one of these institutions has the capacity to improve the system they are locked into, and there is little capacity or incentive for collaborative improvement. An agency may face legal suits if it is either too lenient or if it is too restrictive. You will never understand an institution by looking at their website. To learn how an institution thinks and works you need to talk to insiders. Show them care–its not easy in there. Fortunately citizens can do a great deal of restoration without getting involved in this shit-show, and you might even use it to your advantage. Governments are afraid of community discord, but are equally hungry for community solidarity. Leaders will race to get to the front of a parade that reflects consensus and clear direction. As with land access, government agents often lack the social networks and freedom to do the work of building community vision. Arranging for government approval may seem like a barrier, it may also become a tremendous resource. I would propose that in many situations the inability of governments to support regeneration is more of a symptom then a cause. Our governments are lost in the incoherence and tumult of our colonial culture, just like we are.

—-

These six enabling conditions: project managers, land access, knowledge, cash flow, local agreement, government approval, are common to all scales and types of restoration. For your home garden these conditions will be easy to sustain. To some this list may seem excessive. When your work becomes easy through practice, then teach your neighbor, and then learn how to do more. As we move from parcel to catchment to watershed to ecoregion, we will need to grow into our vision. When ecoregional regeneration is underway at home, move to the next ecoregion and lend a hand.

The purpose of outlining enabling conditions is to help us see them as a shared operating environment, and a context for design. Small actions can cultivate the enabling conditions for larger actions, but only if we see the enabling environment as part of our shared work. In a culture of stewardship our social infrastructure supports restoration. Regeneration would permeate our social lives, and bind our communities. Schools, neighborhoods, religious communities, clubs, societies, and cities would imagine themselves as custodians of watersheds in a way that shapes their relationships.

A Warning

I’d like to offer one warning. Right now, these enabling conditions are scarce, and each institutional workgroup is tempted to act like they are alone and competing in procuring these conditions for themselves. We are conditioned to this narcissistic thinking. A project manager may only think of enabling conditions as a checklist necessary to generate a product for which they will be rewarded. We still see cash flow as the solution to most of our deficits. I’d suggest this perspective is deeply flawed, and undermines the very foundations of our work.

Look at each condition again. These conditions are not objects to be possessed. Each is a process that emerges from relationships. The relationships are complex and overlapping. These enabling conditions are in constant flow and flux. One enabling condition can be used to nurture another. If we are each attempting control within our narrow field of vision, we may not see the web we are weaving as a network of relationships that enable regeneration. If we can see this, we can shape a system that enables restoration as a natural outcome of our social processes. If we can see these enabling conditions as a web of relationships, to which we are all contributing, and by which we are all strengthened, then we are building the culture of stewardship together.

Reconsider each condition. What are the individual interactions that enable these conditions to occur? What are the underlying needs that are at work? What are the existing dynamics that feed these needs and enable these conditions to arise? How are they constricted or constrained? Where are we wasting effort? Your role is not defined by you, but rather by where you place yourself within a web of relationships in a landscape of possibilities. You may need to appear a certain way at a certain time to be effective. Your work on one project, may beneficially enable another unrelated effort. It will serve us to slow our frantic pace, and step back, and consider our shared context.

Dave Snowden is a Welsh technologist who defined the Cynefin (ku-’ne-vin) Framework. He would observe the conditions that enable restoration of landscapes as a “complex problem”– the challenges are not entirely knowable, and not entirely predictable. You can’t plot a course standing on the edge of this uncharted forest. There is no trail. You need to proceed accordingly. Travelling cross country in forest may be a fitting metaphor. You may have a place you are going, but that doesn’t mean you travel in a straight line, or always have your destination in clear sight. You make exploratory moves, and look for patterns: how the undergrowth thins under young conifers; you follow the trails of deer. You test, observe the outcome, and learn from your experiments. You might backtrack or you might strike out boldly.

We get to be a new kind of pioneer. We only get to work one project at a time. By doing the work, we become better able to shape the conditions that enable the work. As each setback and barrier comes into view, never assume it is immutable. Never assume you are alone. Continuously revisit your assumptions about where we are going and the actual nature of the opportunities in front of us. Each project, however small at its inception, offers insight into our culture, and its potential evolution. To capture this insight requires that we become fluent in enabling conditions, and recognize them as a product of cultural infrastructure. That reweaving of culture is our shared project, like a collective unconscious, but corporate and accessible only through doing the work of restoration itself. You cannot learn this forest by looking in from the edge.

If you have read this far, I hope you are doomed to become a project manager. Regenerating the earth is a hard learning path. As you explore the complex territory of the place you inhabit, please notice enabling conditions. Stay focused on gemba. Consider how relationships develop. Test, observe, and take a step. Then test again. Restoration advocate John D. Liu once shared with me a Chinese proverb: “you cross the river by feeling the stones with your feet.”