I’d propose there are three sub-systems to develop in restoration camping: the community, the camping, and the programming. Because restoration camping is so complex, considering these three sub-systems helps us get organized. Our ability to work together depends on developing a shared understanding about the purposes and functions of each sub-system, and the structures and rituals necessary achieve those purposes.

-

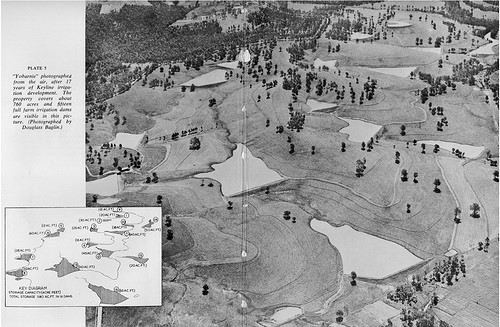

Earthcorps at a morning orientation at Hylebos Creek. There are existing groups with experience training and supporting community action. Community – we need the guild membership to have the ability to aggregate resources and govern and schedule itself. This will necessarily rely on standard processes and agreements and web-based automation, but should not to replace face-to-face working relationships. This community structure will necessarily have social, legal, financial, and informational components that interact. I have assumed that the camp would be best operated as an LLC, because of flexibility of institutional structure, low startup cost, and financial adaptability. However a democratic and cooperative non-profit private foundation would hold collected money, seek sponsorship, acquire and own capital resources, and fullfill its purpose by making gifts and equipment loans to subsidize the operation of restoration camping LLCs. This results in a separation of powers and responsibilities, and a relationship of mutual accountability between a cooperative collective that aggregates and distributes shared resources in service, and entrepreneurial camps that learn to serve the collective in their own way building local knowledge. This pattern allows for rapid expansion and experimentation at camps, while leaning on the foundation as an organizational “backbone”. Training and support in decision making and establishing cultural rituals of inclusion, respect, and transparency will be critical to sustain a volunteer-owned and operated system. Our initial financial and informational needs can be met through a combination of wordpress development, the salish sea wiki, and google tools.

-

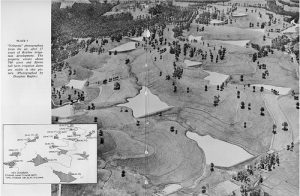

Dispersed camping near Mono Lake clarifies necessity and comfort Camping – we need the technologies, tools, and strategies that let us show up at a natural resources site anywhere in Cascadia, live well, and be able to work. The core technologies are water purification, greywater, and human waste composting, followed by group shelter, cooking and washing, and finally the diverse kit of tools we need to do different kinds of work in different ecosystems. There will be hurdles presented by regulations that generally discourage nomadism, particularly around the composting of human waste. I have imagined we would test and design three kits, each might come on its own trailer: a bathhouse, a kitchen, and a workshop. Each trailer would be self-contained, and expand out into an well-designed system with shelter and all necessary functions. The fundamental capital cost for a new camp are the kits, while operating costs are the wages of the camp steward, insurance, and internet support. I assume we will use solar and LED for minimal electrical conveniences, and high-draft wood burning for energy. A variety of modular structures such as geodesic domes, tepees or long house frames can provide group shelter for dining and gathering, however some kind of sustainable and non-toxic skin could have value (perhaps working with a sail maker on hemp canvas oil-cloth as an alternative to treated cotton, PVC-coated nylon, or disposable plastic tarps.) There is lots of room for innovation and redesign. Initial systems will be hodge-podge, and home-made, with found and adapted components and we will develop from there. These technologies also support disaster preparedness (another potential service relationship.)

-

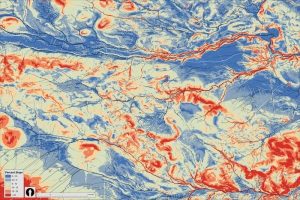

Conceptual design of a typical camp, with a gradient of access and privacy with compact and well organized social and working spaces. Programming – we need the network of professionals that are willing to design and teach so that campers have the support they need to learn through direct ecosystem management. Campers must understand what they are doing, and feel compelled by the value of the service. We would benefit from a design-review rituals that insure all projects are clear, effective, and efficient, and so respect the labor and learning goals of members. Work is a process that has multiple yields. We’ll be more efficient if we can learn to self-organize offerings through an internet platform. Camps may ask for help from the guild with programming and design capacity. Private groups, governments, tribes or anyone who wants to serve through teaching and design could offer experiences. Any member of the guild can volunteer to teach, offer training for a fee, or participate through their day job or business, as mediated by the camp stewards. A critical challenge across ecological field work system will be information transparency and retention. We can use the design and teaching process to build our information resources and the experiential capital of our membership, to then be applied to future work. Our cultural conditioning is for professionals to get paid in cash to lead stewardship. This creates a powerful social barrier to broad-scale ecosystem stewardship action. We’ll need to figure this out.

When these three things converge we have restoration camping. Each of the three sub-systems will push and pull the others into existence, and need to be developed in tandem. They all interact with each other. Because of the number of relationships involved in this system we will do a better job with design if we are doing it. This suggests to me that we begin intermittent camping as soon as possible with what we have in hand, and build from that. The first camp can be sustained by the simplest low tech systems. Each camp informs a period of work before the next camp. For both ecological and practical reasons, holding both dry season an wet season camps make sense (as the Norwegian fisherman says, “there is no bad weather, only bad clothing”)

We could get lost in the complexity of what could be–becoming obsessed with planning to do, rather than letting the doing inform the plan. So borrowing from the software world I have imagined an agile development approach with a focus on the desired future performance, achieved with incremental improvements, with a focus on testing a functioning camp system, rather than preparing for a grant rollout. We continuously pursue a perfect state in a changing context, never arriving, but always adapting and making progress.