Republished from Ecosystem Restoration Camps, the inspiration for the Ecosystem Guild, established in The Netherlands and Spanish Altiplano in 2017.

I live in a temperate coastal rainforest on the eastern Pacific Rim. We have more water than most, but it all comes in winter. Our cold inland sea has four thousand kilometers of shoreline, ringed by snow-capped mountains to catch moist ocean wind. Our trees are legendary–an old forest can store 900 metric tons of carbon per acre. Beyond the Cascadian rim are deserts, drylands, tundra and more mountains for a thousand miles in every direction.

People here lived on Salmon for five thousand years. The salmon need streams with steady flows of cold water. Clearing forest, scraping soil, and pumping groundwater have left many streams hot and shallow in summer. Winter floods scour eggs from the gravel. On October 6, 2016 the supreme court of Washington State ruled that Whatcom County could not legally issue another building permit for a new home unless it could show that there is enough water for each new well. Whatcom County couldn’t show the water.

Washington State water rights are a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces and no picture on the box. I suspect that neither the county, the state, nor the plaintiff knows what comes next. There is often less water in the river than is “owned” on paper. With fish and timber gone, the state economy now scrapes forest duff and builds houses. Our population is growing by 100,000 people every two to three years, surging with in-migration from other parts of the country. The market value of thousands of parcels depends on the ability to get a building permit.

In the political chaos following the court decision, the state budget process collapsed. Civil society picked sides or quietly left the room. Propaganda machines lurched into action. Partisan websites started churning out content. Banks, builders, and big real estate lined up against environmentalists, senior water right holders, and 20 sovereign tribal nations, holding broken treaties that promise salmon forever.

In our green crescent, around a billion liters of water falls on every square kilometer of land–it would form a waist-deep lake to the horizon, if it didn’t run to the sea. Up in the mountains, the deluge would cover our heads and is caught in snowfields, glaciers and forests, recharging sixteen montane rivers. The ocean gives us so much to work with. The Salish Sea is a climatic paradise, neither hot nor cold, with an abundant trading culture since time-before-memory. But unlike the Indians, we couldn’t conceive of living without tillage agriculture. We spent our first colonial generations cutting and burning the forests, just to get down to the mineral soil.

It used to be that all the rain went into the ground, bubbling up in springs, or pooling in wetlands and beaver ponds. Our green crescent will likely remain a climate refuge, even with our unmeasured aquifers and declining snowpack. The future is likely to bring us larger floods followed by longer droughts. So even in one of the wettest places on earth, in the home of Microsoft, Amazon, and Starbucks, full of wealthy environmentalists, our mismanagement of forests and soils, combined with mass migration, will lead to a final struggle over water and our ecological heritage. We are in this together.

When I was a child, and less preoccupied with politics and finances, I knew what to do. When the fall comes, and the frogs sing, you can go to the street and the abandoned lots and play in the rain as it tumbles in from the sea. You find trickles of water and you turn them into pools, with sticks and mud. You capture the rain and put it in the ground.

Perhaps because we’ve had it easy, we don’t have a coherent strategy. The forest practically grows itself. Excavation equipment is parked in every rural neighborhood. Our governments and universities curate more data than anywhere on earth. What we lack is a clear sense of shared purpose. If we can embrace the work of forests and beavers, there will be plenty of water, and therefore abundance. But if you read the political tabulation of popular concerns, hydrology is not even on the list. It is as if we live in an imaginary world, full of scarcity and fear, but disconnected from the pulse of the earth.

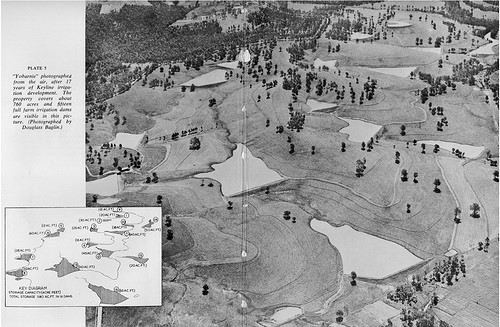

If we look to the drylands, people have been living with drought for generations. Percival Alfred Yeomans was a Australian mining engineer in the 1950s who had excavators parked in his rural neighborhood, time on his hands, and a sharp mind. He proposed a radically simple approach to landscape management, and an alternative to large scale water projects: first study the topography, understand the flow of water, and then design distributed systems to catch and store water in the ground and in ponds. He developed perhaps the first integrated ecosystem planning strategy written in English. It is brilliant, somewhat poorly written, and no one in my neighborhood has read it.

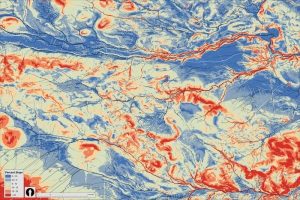

Unlike P.A. Yeomans or my child self, we have abundant tools to help us think about water. Digital elevation models give us a mathematically precise grid of the earth’s surface. Water always goes downhill. With a few keystrokes we can predict in detail where water will flow across an entire watershed. Each vein is fed by an easily delineated catchment dressed in a tapestry of forests, fields or parking lots, soils, and shallow geology. First study topography, understand the water, and design the rest to follow. Patterns of slope mark opportunities where water will either soak or seep. Well logs let us look at water levels underground. We can locate every landowner parcel in its hydrologic context. An umbrella walk in winter storms can verify the details. All restoration is local, so knowing each place is required. Could we cultivate a new picture of our rainforest home, door by door? If we can understand our purpose, the topography and water will show us the trail. All good adventure books have maps under the front cover. Hydrology is the foundation of ecological restoration. And so stewardship of water is the great work of our time, not only for its moral or aesthetic merits, but for its contribution to our well-being.

There is a new language to learn so we can think and talk about land and water. Yeomans gave a name to the points in a primary valley where slope changes from steep to gentle; the first places where water can be held efficiently with the cut and fill of earthen dams. Yeomans drew lines falling slightly off contour where stormwater flow might be pulled out to saturate ridges. Even as he dug his earthworks, he designed new tools to incrementally deepen soils across his fields and guide the flow of shallow groundwater. His New South Wales was an ancient landscape of clay hills worn round. My post-glacial plateaus are fresh carved with piles of gravel lying around. The first Ecosystem Restoration Camp is on an incised semi-arid high plateau. But his vision was not a religion. It is a pragmatic story of personal stewardship, an open-eyed conversation with reality. Topography defines opportunities that we need to train ourselves to see. When knowledge of purpose is coupled with knowledge of place, we are ready to learn this new language.

Our challenge is to create a community in every catchment in every watershed that can remember and teach this work. If we do well, the stewardship of water will become a new story, with hydrological knowledge as a common language. A simple understanding of topography and water may help free us from the well worn ruts of political contestation. Can we be lifted by a visceral impulse toward stewardship? This is not a challenge solved by passive opinionation. Yet it is a work full of joy, because our hearts feel gratitude for an abundant land. All the skills and technologies are in hand, the greater challenge is to learn how to do this thing together, not as special interest groups, or isolated subcultures, but as communities of free people.